S1: Episode 6

Operation Silver Shovel

A criminal flips and wears a wire. Aldermen accept small sums of large bills. The FBI’s investigation may be tainted. “Mount Henry” grows, but shrinks from memory.

Episode | Transcript

Operation Silver Shovel

Corrections and clarifications: A Facebook post, tweet and previous version of Episode 6 of The City podcast misidentified the number of silver pieces Judas received for betraying Jesus. He received 30 pieces.

Robin Amer: On the evening of October 21, 1994, an Illinois State Representative named Ray Frias paid a visit to John Christopher’s South Side office. The low-slung, unassuming brick building on West 74th Street was on a block that dead-ended by some train tracks, making it an ideal location for a clandestine meeting.

The meeting was captured on video, and in it, you can see Ray Frias and John Christopher seated at a wooden table in the middle of a plain-looking office with dingy carpet and beige walls. The table is strewn with papers. There’s a mini fridge and a rotating fan.

Ray Frias wears a dark suit and patterned tie, and sits with his hands folded in his lap. John Christopher wears a blue polo shirt, and lights a cigarette.

John Christopher speaks first.

John Christopher: OK, what would you feel like, what would you, what would you need, Ray? Could I, you want me, what would you need?

Ray Frias: What, I don't know. To be honest with you, I mean...

John Christopher: This is on a, you want a lump sum or a weekly for next year?

Ray Frias: Uh, weekly'd be preferred.

Robin Amer: John Christopher has called this meeting because he wants Ray Frias’s help getting one of his construction companies certified by the state. And in exchange, Christopher is willing to pay Frias a “consulting fee.”

John Christopher: OK. What's fair with you? Spit it out. Don't—

Ray Frias: You tell me. I mean what's it worth to you? I don't know. I mean I can't come in here…

John Christopher: What could, what do you, here, what do you believe you could do for me? Do you believe you could help me?

Robin Amer: What you’re hearing is tape of John Christopher attempting to bribe a Chicago politician. Eventually they agree that $500 a week is a fair price for this exchange.

John Christopher: Would you feel 500 a week is OK to start? Till it proves out?

Ray Frias: Sure.

John Christopher: OK, and to give me a promise to act as an official capacity. That's as simple as that. Is that agreed?

Ray Frias: That's agreed.

Robin Amer: In previous episodes, we’ve had actors dramatize John Christopher’s time in court, because all we had were transcripts.

But this is actually John Christopher. This tape is real.

This recording is one of more than 1,000 audio and video tapes John Christopher made in secret while he was working undercover for the FBI. And it’s one of nine tapes we got by suing the FBI earlier this year.

It took us almost three years to get these tapes. And even though we only got nine, they provide a front row seat to how John Christopher operated as the FBI’s prize informant.

Back in John Christopher’s office, he and Ray Frias had settled on $500 a week for this “consulting fee.” But then Frias gets nervous.

Ray Frias: I'm a little, uh, tentative right now also. I mean this is…

John Christopher: What are you tentative about?

Ray Frias: I... I've never made any kind of arrangement like this before.

John Christopher: OK.

Ray Frias: As a legislator. So, uh…

John Christopher: Well, why do you think you're a legislator for?

Ray Frias: Mmm, making money.

John Christopher: Thank you.

Ray Frias: That's what, that's what life's about…. Exactly.

John Christopher: OK, well, I mean, what'd you think, yeah, life's...That's right. Makin' money.

Ray Frias: That's what life is about, makin' money. If you can't make money, then...

John Christopher: You think the politicians, what do you think, they get elected and they don't take money? … You just gotta find the right group.

Ray Frias: Right.

Robin Amer: As Frias starts to come around, John Christopher pushes harder to seal the deal.

John Christopher: I'm here to pay money. OK, and the only reason why you're sitting here is because you are a state legislator. OK? 'Cause I can't make money the other way. … Is that fair enough? So if you feel—

Ray Frias: Sounds good to me.

John Christopher: —uncomfortable with everything I said, OK, then there's somethin' wrong with you. Because there's no politicians in this world that I know that don't do, “Give me this and I'll give you that.”

Robin Amer: “You give me this, and I’ll give you that.” It’s the transactional nature of Chicago politics—I give you a dollar, you vote for my candidate. You vote for my candidate, I give you a job. As we previously learned from the story of North Lawndale alderman Bill Henry, it’s the “Chicago Way.”

But in this case, it's not business as usual. It's what the FBI would call a “quid pro quo”—that's “this for that” in Latin, and it’s illegal. You help my company get certified, and I’ll give you $500 a week. Quid pro quo.

After the FBI had busted John Christopher for bank fraud—for falsifying his loan applications and walking away with millions of dollars he’d use to build up his businesses—the FBI flipped him, convinced him to wear a wire, and put him in the center of a new investigation.

So wearing a wire and acting on the FBI’s behalf, John Christopher went looking for dirty politicians. He found many who were willing to conspire, and some who were less so. Almost all of his targets were black or Latino, and came from segregated neighborhoods that industry had left.

The FBI called this new undercover investigation Operation Silver Shovel. “Silver” like the 30 pieces of silver Judas got for betraying Jesus. And “Shovel” like the bulldozers at John Christopher’s dumps.

The investigation was intended to tackle public corruption and would become one of the biggest corruption probes in Chicago history.

But as it unfolded, Operation Silver Shovel seemed to replicate the harm John Christopher had already caused in North Lawndale. And became a grab bag for anything the FBI thought John Christopher could help them do.

I’m Robin Amer. From USA TODAY, this is The City.

ACT 1

Robin Amer: In July 1992, FBI Special Agent Jim Davis was put in charge of Operation Silver Shovel, and assigned to be John Christopher’s handler.

Jim Davis: I had a sense that this was going to be a big case. We told headquarters about the people that he had been paying recently, who we thought he could pay in the near future. We worked on scenarios under which we could pay public officials.

Robin Amer: After John Christopher crossed over and started working with the FBI, he told the bureau about his bribes to former North Lawndale alderman Bill Henry. You’ll remember he was the wheeler-dealer who had reportedly given John Christopher permission to set up his rock crushing operation in exchange for $5,000 a month.

But the FBI couldn’t start with Bill Henry. Jim Davis is a kind of flippant about why.

Jim Davis: Yeah, I think he was dead before our case started. Otherwise, we'd have paid him. (laughs)

Robin Amer: Instead they started with other officials John Christopher claimed to be bribing:

There was an alderman named Virgil Jones, a former cop from the mostly black 15th Ward. Virgil Jones had also given John Christopher permission to dump in his ward in exchange for a bribe—$10 a load.

Then there were high-level officials from Chicago’s water treatment agency.

Jim Davis: John was in the middle of a relationship to pay those guys for some sub-contracting work on a construction project that was going on at that time.

Robin Amer: But Jim Davis and his fellow FBI agents suspected that with an informant like John Christopher, they could find even more city officials to bribe—ones John Christopher had yet to meet.

The FBI needed to catch them misusing the power of their office to help John Christopher in exchange for money. They needed to establish a quid pro quo. And they had to get it on tape.

John Christopher had a ton of credibility with other criminals, but Jim Davis knew that he would have zero credibility with a jury. John Christopher had an extensive criminal history—bank fraud, trying to murder a federal witness. The FBI didn't want to risk putting him on the stand, where the defense could play up his laundry list of past crimes.

So every time John Christopher went out, Jim Davis wired him up to record his conversations.

Jim Davis: The technology for recording conversations was changing very quickly at that time, so we started out with a thing called a Nagra, N-A-G-R-A, which was a pretty-good size. Like, scary big.

Robin Amer: Like a reel-to-reel tape machine?

Jim Davis: It was a reel-to-reel tape machine.

Robin Amer: Wow.

Jim Davis: And so hiding that was difficult.

Robin Amer: Though Jim Davis wouldn’t tell me exactly where he hid the device.

Jim Davis: Yeah, I don't want to go into that.

Robin Amer: (laughs) OK.

Jim Davis: And understand why, right? I'm not trying to be evasive or secretive or anything. And I just don’t want people really dialed in our techniques.

Robin Amer: You want to protect future investigations? By protecting that information?

Jim Davis: Right.

Robin Amer: As they started to select their new targets, they came up with a plan that was supposed to meet specific legal requirements.

Jim Davis: We couldn't just kind of throw out a net and gather up these guys. We had to make sure that we had some predication that they were involved in criminal activity.

Robin Amer: “Predication” means that there had to be some evidence that the person they were going after was already doing something illegal, and thus might be willing to do more illegal stuff. Often times they’d establish that through a politician’s own network.

Jim Davis: You know, one alderman would introduce us to another to another to another...

Robin Amer: John Christopher may have disappeared from North Lawndale, but you could find him dining with elected officials all over town.

You could find John Christopher at the iHop at 94th and Western. He’d be sitting across from Alderman Virgil Jones, who had given him permission to dump construction debris on the South Side. The FBI listened in as John Christopher gave Jones $4,000 wrapped in a newspaper.

You could find John Christopher at Theodore’s on 95th Street. There, he asked another South Side alderman to send a city street sweeper to clean up the mess he’d made at a job site. He offered that alderman more than $5,000 in cash.

And, you could find John Christopher at Jaxx, a fancy English restaurant overlooking the Magnificent Mile shopping corridor. There, he gave a water commissioner a cigarette pack filled with 40 rolled $100 bills.

To aid this growing investigation, the FBI brought in an undercover agent to act as John Christopher’s “business partner.” Mark Sofia was a veteran FBI agent from Chicago, who was also Italian. Although he was more clean cut and well-spoken than John Christopher, the bureau thought that he could play a convincing mobbed-up construction guy. He was often in the field with John Christopher when he bribed public officials.

During the investigation Mark Sofia went by an alias: “Mark Dahlonega.”

Jim Davis: We wanted him to be Italian. I mean, Mark Sofia is Italian, but I have him pick a name that basically ends in a vowel, and I didn't realize it until we had been in this for a while, and I said, "So, where did you get Dahlonega?"

Robin Amer: Dahlonega is not an Italian name.

Jim Davis: And Mark was a West Point grad and an Army Ranger, and the third phase of ranger training is based in Dahlonega, Georgia.

Robin Amer: And like his fake business partner, “Mark Dahlonega” was also all over town...

Meeting with a state rep at a diner near Midway Airport, where he handed over the $500 John Christopher had promised.

Or hunkering down in an undercover apartment in suburban Oakbrook Terrace, where he’d sometimes pay bribes in his bathrobe and count out money on the coffee table.

Mark Sofia: So, I saved about two grand based on the two weeks and so your share of that would be one grand? Is that fair?

Robin Amer: In this video recording, Mark Sofia as Mark Dahlonega is paying a South Side alderman for helping John Christopher clean up a parking lot repaving job.

Jesse Evans: Yeah.

Mark Sofia: OK. I don't want to short you. OK, sir.

Robin Amer: It’s a little hard to hear, but that’s Mark Sofia actually counting out money to give to the alderman.

The FBI cast a wide net. Between the two of them, John Christopher and Mark Sofia eventually tried to woo and then bribe at least 40 people.

There were so many targets, and each had his or her own story. But let’s drill down into one of these officials to better understand how this investigation played out in practice, and what it felt like to be caught in John Christopher’s web.

That’s after the break.

ACT 2

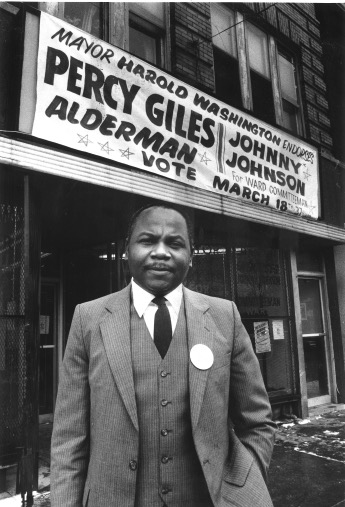

Robin Amer: Earlier this year, I visited Percy Giles, a former West Side alderman who got caught up in Operation Silver Shovel.

Giles lives in a tidy, split-level ranch house on a quiet, tree-lined street in Chicago’s south suburbs—very different from where he grew up in rural Arkansas.

He was one of 10 children and the son of a sharecropper. The family’s home didn’t have indoor plumbing until after he was 10 years old. Giles went on to study at the University of Arkansas, and then, like so many other black Chicagoans, he left the south as part of the Great Migration and made his way to the West Side.

Giles would become part of the wave of young black politicians who came up under the city’s first black mayor, Harold Washington. In 1986, when he was in his mid-30s, Giles was elected to City Council.

Even today, if you ask Percy Giles what accomplishment he’s most proud of from his time in office, he’ll tell you it was getting garbage out of his ward.

Percy Giles: If you're familiar with the West Side Chicago, it always got the reputation of being not clean. And everybody looked down at the residents on the West Side. But what I determined right away is that the West Side wasn't treated fair.

Robin Amer: Percy Giles’s ward, the 37th, was and still is similar to North Lawndale: majority black, not a lot of clout with City Hall, and chronically underserved by the city—the same set of factors that had prompted North Lawndale alderman Bill Henry to buy his own street sweeper.

When Percy Giles was first elected, the city had insisted that ten West Side wards, including his, all send their household garbage to a local incinerator. So the alleyways in his ward became clogged with bulkier items, like couches or TVs, that couldn’t go in the incinerator.

Percy Giles: And they let this other stuff just, people put it out there, it just sit out there and just soak. The city claimed that they would send a bulk truck there to pick it up later. But they they didn't do that.

Robin Amer: Eventually, Percy Giles convinced the city to let him send the ward’s trash to another site, and that got the garbage problem under control.

Percy Giles: If I have to say the one thing that I did as alderman that was the most significant thing, I would say that would be it. Because that changed the fiber of the West Side.

Robin Amer: And yet, Percy Giles was eventually taken down by an undercover investigation that started with a mountain of waste.

By January 1995, Percy Giles had already served two successful terms as alderman and was running for a third.

Percy Giles: And election time comes, we all ready to look for ways to raise funds.

Robin Amer: Giles got a call from a political consultant he’d hired. The consultant had scheduled a lunch with a possible donor named John Christopher.

Percy Giles: “I got this guy, John Christopher.” He said that, you know, “He'll help us raise some money.”

Robin Amer: A few days later, Percy Giles and John Christopher met for the first time at a West Side soul food restaurant called Edna’s. Edna’s advertised “the best biscuits on earth” and had a back room where VIPs could meet in private.

Percy Giles: Where do you see this short ribs of beef on here? Is it on here? Oh, it's not on here. Well, I have the short ribs of beef.

Robin Amer: That’s Percy Giles ordering the short ribs. He’s hard to hear in this tape because the tape recorder is across the table from him, hidden somewhere on John Christopher’s body. So in all of these recordings John Christopher is much easier to hear.

John Christopher: OK, um. You know, I seen, I see a hot dog that was burnt. What is that, a Polish sausage?

Server: No, that's a hot link.

John Christopher: Give me a hot link, burnt.

Server: OK, hot link well.

John Christopher: I'm in your guys’ neighborhood here, you know? (Laughter) I’m used to going to the Italian neighborhood.

Robin Amer: John Christopher and Percy Giles finish ordering and start making small talk. Giles asks how he's been in doing, and John Christopher lifts up his shirt.

John Christopher: You know what? I'm losing weight or gaining a little weight, but I'm doing alright, though. I been staying out of trouble. Well, you know, when I'm with my wife I gain weight when I'm away from her I lose weight.

Robin Amer: As he lifts up his shirt, he grabs his belly, and shakes it up and down. FBI agent Jim Davis would later tell me that when John Christopher did this—lift up his shirt—it was his way of signaling to Percy Giles or anyone else around that he was not wearing a wire. Though, of course, the only reason we’re hearing this, is because he was.

And as they’re making small talk … talking about the upcoming mayoral election and who’s ahead in the polls … that kind of thing … John Christopher brings up his dumps in North Lawndale.

John Christopher: So the good news is I’m out of the dumping business.

Percy Giles: Mmm hmm.

John Christopher: I don’t do that no more.

Percy Giles: Mmm hmm.

Robin Amer: Giles says to Christopher, “You’re known all over the city.” In other words, you’re infamous.

Percy Giles: You're known all over the City.

John Christopher: I'm known why?

Percy Giles: Well you're known, when I talkin' about the city I'm talkin' about, uh, from, from my meetings with, uh, Henderson.

Robin Amer: “My meetings with Henderson.”

John Christopher: Oh, my buddy.

Robin Amer: Percy Giles has heard about John Christopher and his construction debris dumps from Henry Henderson, commissioner of the city’s Department of Environment.

And now, for the first and maybe only time, here is John Christopher, on tape, defending his actions in North Lawndale.

John Christopher: OK, listen. We're no altar boys at this fuckin' table. Let’s put it on the table here.

Percy Giles: Right.

John Christopher: I made a lot of money over there.

Percy Giles: Mmm hmm.

John Christopher: And I got no bones about saying I had, made a lot of money, and you want to know somethin'?

Percy Giles: Hmm?

John Christopher: My intentions weren't to hurt nobody there. I created jobs there.

Robin Amer: Percy Giles seems sympathetic to John Christopher. Giles explains that he had been meeting with Henry Henderson because he’s now facing a similar situation to the one in North Lawndale. He had thrown his support behind a company called Niagra that had promised to bring 80 jobs to his ward. Niagra then set up a construction debris dump next to a beauty supply factory. The dirt and debris were now piled so high that run-off from the dump had flooded the factory’s parking lot.

Percy Giles was now taking heat from the factory’s owners and the city and the press, including a reporter from the Sun-Times.

Percy Giles: I just told her, I say well, “Look, I don't consider it to be no damn dump,” and I explained to her what it was, and she couldn't really say nothin'.

Robin Amer: His political challenger in the upcoming election had also started using the dumps against him, putting up flyers around the ward that said the dump was toxic.

Percy Giles: And plus, uhm, uhm, in light of my opponents and shit, they, they can't do a goddamn thing now, because ain't nothin' goin' on up there now number one. And plus they already done put shit all in the community, talkin' about a toxic, I mean he lyin', saying it's a toxic dump.

Robin Amer: So John Christopher offers Percy Giles some words of wisdom.

John Christopher: I just gonna give you a piece of advice: watch the heights of it.

Percy Giles: Mmm hmm.

Robin Amer: “Watch the heights of it.” In other words, be careful how big the dump gets, especially when you’re running for re-election.

John Christopher: I'm just giving you—I feel that if you're gonna be with somebody, give him all the information you could. To help him out later on, OK. And, uh, I was the first one basically that started all the dumps, you know?

Percy Giles: Mmm hmm.

John Christopher: The first. Right, so, listen, uh, Pere, uh, Mr. Percy Giles, let me say it this way to you. OK, you have a nice deal. You're the alderman. OK, you're runnin' for a long time. OK, I went through eight months of courtroom battles with city and federal.

Percy Giles: Mmm hmm.

John Christopher: You know I started a can of worms in the city.

Percy Giles: Mmm hmm.

John Christopher: That could haunt you for years to come. You know that's how Jesse won the election.

James Blassingame: Jesse?

John Christopher: Miller. Oh sure. And all you need is a couple people calling up and saying they got dust problems.

Robin Amer: Jesse Miller, who won Bill Henry’s seat, after the former alderman supported John Christopher and the North Lawndale dumps.

Again, this is a warning: Learn from what happened in North Lawndale.

John Christopher: Uh, take it from me. Would you take that from me?

Percy Giles: (Laughing) Sure.

John Christopher: OK?

Percy Giles: I hear ya.

Robin Amer: John Christopher’s advice may have been offered one businessman to another, but he’s here to do another kind of business. And all this small talk was probably just to establish trust. Because once they’ve built that rapport, John Christopher goes into deal-making mode.

First, he tells Percy Giles that he has a new construction company.

John Christopher: Do small work.

Percy Giles: Mm hm.

John Christopher: Couple million here. Low key, real small.

Robin Amer: John Christopher explains that on paper, his new construction company is run by a guy from North Lawndale—actually the same guy he’d hired to do “community relations” in the neighborhood back when he was fighting the city’s lawsuit. And because this guy is black—and fronting as the official head of the company—that makes them eligible for contracts set aside for minority-owned businesses.

John Christopher: I am not around anybody when he, when he goes in for the job. … And if my name is mentioned, he pulls that radical stuff and says, “What is this shit? He caused me enough problems.” And he calms it down, you know? I mean, he really fights for it.

Jim Davis: That's all very good tape. We want to dirty these guys up.

Robin Amer: That’s Jim Davis, John Christopher’s FBI handler. He was one of the first people to hear this tape after it was recorded.

Jim Davis: You've got this white, Italian guy talking to a black elected official and saying, "Hey, we're taking advantage of the MBE certification.”

Robin Amer: MBE stands for “minority business enterprise.”

Jim Davis: By saying that, “We are a minority-run business when, in fact, look at me.” And to have those conversations in front of the alderman and have the alderman not say, “Hey, you can't do that,” that paints the alderman in a certain light.

Robin Amer: After explaining that he’s basically set up a front company, John Christopher makes his pitch: He wants a contract for a shopping center being built in Percy Giles’s ward.

John Christopher: I want the excavating work at a competitive number.

Percy Giles: Mm Hm

John Christopher: OK?

Percy Giles: OK. You want to compete for the excavating work?

John Christopher: I want a piece of the excavating work

Percy Giles: Alright.

Robin Amer: In exchange for this help, John Christopher offers Percy Giles $10,000.

John Christopher: OK. For that $10,000 you're gonna, what's gonna happen here is basically an effort to be given. OK? A commitment of trying to get some work is that what we're saying here?

Percy Giles: Mmm hmm.

John Christopher: You, you know what I'm sayin'?

Percy Giles: Yeah...yeah 10 is all you need. What you get for 10 is that, you gonna have somebody like the shopping center, we'll do all we can, everything, I can't guarantee nothing hundred percent. We'll do all we can to lobby in your behalf for the excavation work, for, uh, if you apply for work in the city if you're, you're the low bidder. We'll be happy to make calls to our contact at the mayor's office to help with that. Uhm, anything, any way that we can be of assistance. You got somebody you can call that will do, do all they can to help.

John Christopher: That's all that's needed.

Robin Amer: “That’s all that’s needed.”

But John Christopher actually needed to get the payment on tape. So a few days after that first lunch, John Christopher and Percy Giles met at Edna’s again. And this time, John Christopher brings the money with him—the first of two payments of $5,000 each.

What follows is very hard to hear, because even John Christopher is speaking in a hushed voice. He says to Percy Giles, “Here’s the five thousand. It’s all there.” He asks Percy Giles if he wants to count it.

John Christopher: Here, let me, here's the $5,000, it's all there, you don't, you want to count it. It's there.

Percy Giles: No, no, uh-uh. Uh, what I got to lose.

John Christopher: Would you please hurry up and put that in your pocket?

Percy Giles: I will.

John Christopher: Jesus.

Jim Davis: By John saying, "Please hurry up and put that in your pocket," it dirties this up more. He's saying, "Let's not make a big spectacle out of this," even though he is kind of making a big spectacle out of it.

Robin Amer: Giles sounds giddy as he take the cash.

Percy Giles: That's really gonna help.

John Christopher: I'm not bullshittin'. This is serious shit. This is all.

Percy Giles: I know that's what I'm sayin'.

John Christopher: OK?

Percy Giles: That'll help, that'll make my campaign.

John Christopher: I don't want to hear nothin' about fuckin' campaigns. They're all full of shit.

Percy Giles: I’ll win the election. I’ll win the election. (laughs)

Robin Amer: To FBI agent Jim Davis, this is a slam dunk. They have a sitting alderman, on tape, taking money from their informant.

But that’s not how Percy Giles sees it. Giles admits taking the money, but swears he thought it was a campaign contribution. It’s why, when he takes the money, he says, “I’ll win the election.”

Percy Giles: In the African-American community, it's difficult for us to raise money for elections. And that was like the best fundraising that I had. And that really did help me buy materials and stuff for real.

Robin Amer: What did $10,000 mean to your campaign efforts at the time?

Percy Giles: It meant a lot. I mean it was about, it literally at that time, that was about a third of my campaign dollars. Yep.

Robin Amer: So this is a really big deal for you, because you're running for reelection. You have a meeting with this guy that you think is a local businessman, and he's effectively just given you in, like, two face-to-face meetings a third of the money that you've raised so far for your election campaign.

Percy Giles: I thought that it was a blessing for me, for my campaign.

Robin Amer: Percy Giles says he’s still bewildered as to why the FBI chose him as a target. He argues that the FBI turned an otherwise loyal public servant into a figure of corruption.

Percy Giles: They sent somebody to me to manufacture a crime that they say that pro quo, or whatever it is, quid quo. They manufactured that. Then they say, “Oh, we got him. He committed a crime.” I wasn't doing anything to anybody but taking care of my business in my ward.

I just don't think that's fair. I mean, to me you can do that with anybody. I mean, some people are smarter than me. They are more politically astute than me. They were born around families that, who has been having business. They know how people are. But I came from a background that nobody told me any of this. I came from Arkansas. I just, I'm not used to nobody. Arkansas is a hospitality state. And Arkansas people, they pretty much say what they mean, and they mean what they say. And that's where I come from. And so that was just a shock to me.

Robin Amer: Percy Giles was eventually indicted and convicted. Not just for taking $10,000 in bribes from John Christopher, but also for taking $81,000 in bribes from Niagra, the company that set up the dump in his ward. When he talks about it now, he says the money was for the ward, and Niagra told him it would bring jobs.

Percy Giles would not be the last person to critique Operation Silver Shovel. Or the last alderman to get caught up in the investigation—in ways that mirror John Christopher’s time in North Lawndale.

That’s after the break.

ACT 3

Robin Amer: Although the FBI was successfully going after elected officials by offering them bribes in exchange for contracts or help from the city...

Jim Davis: It was often very hard for us to find something that these guys could do for us that we could pay them for.

Robin Amer: Because, as Jim Davis points out, there were a lot of rules that limited what the FBI could do.

Jim Davis: So, we would have conversations where it was very clear that they wanted money from us, and that they would do whatever we asked them to do. We just couldn't figure out what it was that we could ask them to do that wouldn't create uncontrollable third party liability.

Robin Amer: “Third party liability” means harm to anyone who was not a target of the investigation.

For example, if they got a city contract, it meant that another, legitimate business, would not get that contract.

Jim Davis: In some of the rock crusher scenarios that we ran as part of this investigation, if we set up a rock crusher in a neighborhood, there was impact on the people around where the crusher was placed.

Robin Amer: “Some of the rock crusher scenarios.” The FBI sent John Christopher to other aldermen to ask if he could set up other rock crushers in other wards.

Almost always majority black or Latino wards.

But Jim Davis is careful to say that, because of concerns about third party liability, the bureau never actually set up any rock crushers anywhere.

Jim Davis: We never placed, actually placed, the rock crusher anywhere.

Robin Amer: Instead, Jim Davis says they would bring politicians to another rock crusher John Christopher had. This one also predated Operation Silver Shovel, and was out in Lamont, in the western suburbs. Jim Davis called it a “half-million dollar prop”—in other words, an expensive piece of equipment that was meant to be seen but not used.

Jim Davis: So the crusher operated out in Lamont, and we would take alderman out to Lamont to see the crusher, so they could go out and see the thing in operation.

Robin Amer: And then, once the alderman had seen the rock crusher…

Jim Davis: We'd identify a lot in their ward and say, "This is where we want to put it." We would get their support, pay them for their support, and then we'd never put the crusher there.

Robin Amer: In practice, this was extremely confusing for the aldermen.

Here’s what it looked like to Larry Bloom, who was then the alderman of the Fifth Ward.

Larry Bloom: He told me that he needed some overflow space because the space that, to which he was bringing the cement debris was, uh, he needed more space. And would I help him find such a space?

Robin Amer: Bloom was the only white politician caught up in the probe. He was known as an independent and a reformer. His South Side ward included the integrated Hyde Park neighborhood, home to the University of Chicago and the Obamas. The ward also included a majority-black neighborhood called Grand Crossing that had land zoned for industry.

Larry Bloom says he first met John Christopher a decade before, when John Christopher was a client of another lawyer in Bloom’s practice. They reconnected in the mid-90s when they ran into each other at the Standard Club, a fancy, downtown, members-only club where Bloom was meeting a potential campaign donor.

Larry Bloom: I think I was putting my coat down. And I see across the room this big smiley guy, his eyes get wide open, and he sees me and comes running over to me and says, "How you doing, Larry?"

Robin Amer: It was John Christopher. And later, in his usual pushy way, he asked Larry Bloom to find him a place to set up a rock crusher.

Larry Bloom: I actually did that. I actually drove around, and I found a location that was in the new portion of my ward hadn't known about earlier, which was separated by the rest of the neighborhood by going underneath a tunnel and then you went to this open area and it was basically a construction-related company that used it for storing its vehicles.

Robin Amer: John Christopher paid Larry Bloom $2,000 for his help. And after securing the site, and supposedly setting up shop there, he came back to Alderman Bloom.

Larry Bloom: And he said, “Larry, I think I'm messing up the alley when I'm bringing this debris over to the site. Can you have the ward superintendent go out there and clean it up?”

Robin Amer: And after the ward superintendent checked out the site, he told Bloom, there’s nothing there. No dirt, no debris, no rock crusher.

And yet, John Christopher calls again, and again asks Larry Bloom to clean up the site. And he is really pushy. So Larry Bloom goes and looks at it for himself.

Larry Bloom: There was nothing in the alley. And I think I looked into the yard and I didn't see any debris in the industrial yard itself. I didn't see any of the stuff that he said he was bringing in.

Robin Amer: This story basically confirms what Jim Davis told us—they never put a new rock crusher anywhere.

But from what we can tell from our reporting, that’s not quite true.

During his time as an FBI informant, John Christopher kept dumping at least two sites, including the ones in North Lawndale. He also set up at least one rock crusher in a place where there had not been one before.

John Christopher had been dumping in the 15th Ward before he was recruited by the FBI. He had help from the alderman we mentioned earlier—Virgil Jones, the former cop, who took $4,000 wrapped in a newspaper.

Photos of that dump show something similar to what existed in North Lawndale: An enormous pile of concrete slabs stacked what looks like two stories high.

According to court records, John Christopher kept dumping here after he became an FBI informant. And in August 1992, one month after Operation Silver Shovel officially began, he put a rock crusher at the site and operated it for at least a few months.

After we learned about this rock crusher, we went back to Jim Davis, to ask if he’d been mistaken when he said they’d never actually put any rock crushers anywhere. He reiterated that as far as he could remember, they never had.

But he did know about this one, at least at one point. During Virgil Jones’s trial, Jim Davis testified under oath that he had gone to visit the site in the fall of 1992, and saw the crusher in operation.

So it’s not completely clear, but it seems as if John Christopher initially set up this rock crusher behind the FBI’s back. In a previous interview, Jim Davis told me that John Christopher would often do this kind of thing behind his back.

Jim Davis: There were a couple of times where I went down to John's office, which was down in the … I think it was in the 76th and Western area, somewhere down there. And I'd walk around his yard, and I'd see some piles of dirt building up, and I would tell him, "Get rid of those." So, that's what he has a tendency to do. And we had to go out there, and every once in a while, tell him, "You can't do that. You need to get this dirt out of your lot."

Robin Amer: But that didn’t mean the FBI didn’t use this rock crusher to its advantage. The payments made to Virgil Jones for helping with this operation were part of the FBI’s case against him.

We reached out to Virgil Jones, but he never responded.

At this point, we should take stock of all the politicians Operation Silver Shovel targeted. There was Percy Giles, who is black. Virgil Jones, who is black. Ray Frias, Latino. Jesse Evans, black. Allan Streeter, black. In fact, every public official indicted in Operation Shovel was black or Latino, with the exception of Larry Bloom, who is white and Jewish.

Jim Davis says this disparity bothered him—even at the time.

Jim Davis: We were looking for opportunities to try and branch out racially, but the issue was that we could only go where the case took us. We could only go where our subjects were willing to introduce us. I remember at one point having conversations about, "Is there any way that we could get John to say to Allan Streeter, ‘Do you know any white politicians we can pay?’” We didn't do that just because it would have been ridiculous to do it. It would not have been a conversation that I think I would have worked in the undercover scenario, but—

Robin Amer: Why? Because then the question is, “Why would you ask me that? That's kind of a weird thing for you to ask me,” right? Is that your concern?

Jim Davis: Exactly, and so we went where the case took us.

Robin Amer: He says the path the investigation took is just evidence of the city’s longstanding racial divides.

Jim Davis: The reality of Chicago is that, I believe, that black politicians know black politicians, work with black politicians, and the white politicians work with the white politicians. I frankly think that Chicago is one of the most segregated cities in the country, and—

Robin Amer: Yeah, you're not alone there.

Jim Davis: And that's why this case seemed focused on black politicians.

Robin Amer: That segregation was a driving factor here makes sense. It’s the scaffolding on which you can hang almost every other fact about Chicago.

The neighborhoods where John Christopher set up his dumps and rock-crushers—neighborhoods like North Lawndale—were black neighborhoods, but they were also neighborhoods that had gradually seen industry leave. They had a lot of vacant land and the land was not redeveloped quickly, because it was not as valuable as land was in wealthier, white neighborhoods, where developers were more interested in building.

Which meant that when John Christopher was looking around for places he could convincingly put a dump or a rock crusher, even a fake one, he almost certainly would be looking in South and West Side wards, where land was cheap and plentiful and set up for industry. There just aren’t nearly as many undeveloped lots on the North Side.

It wasn’t just that there weren’t any white politicians—other than Larry Bloom—caught up in Silver Shovel. There weren’t any North Siders either.

There’s one other dimension to this story we have to talk about. As Operation Silver Shovel broadened, it got weirder.

Apart from bribes for city contracts and rock crushers, Silver Shovel became a kind of kitchen sink for everything the FBI thought John Christopher might be able to pull off.

That included fake legislation about cemeteries aimed to lure in lawmakers at the Illinois state capitol. And a scheme that involved a Green Card and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. And a drug deal involving 2 pounds of cocaine. And a money laundering operation for the Chicago Outfit.

None of it had anything to do with North Lawndale. The only thing these parts of the investigation had in common was John Christopher.

Jim Davis: So, at this point, John is in a little bit of a state of denial, right? He wants for this investigation to go on forever, because he knows when it's over, he's going to have to leave. He's going to have to tell his family that he was cooperating with the government.

Robin Amer: Eventually, this case would go public. And John Christopher’s targets would have their day in court. And then, the FBI would have to contend with the reality of who John Christopher was, and all the things he’d done.

I asked Jim Davis how the bureau justified working with a man like John Christopher. And he told me something that he had he once heard a lawyer say in court. Something that stuck with him.

Jim Davis: “Sometimes if you're going to prosecute the devil, you got to go to hell to get your witnesses.”

Robin Amer: In January 1996, Operation Silver Shovel would break as front page news. Ray Frias, the politician we heard at the beginning of this episode, would be acquitted.

But Virgil Jones, and Percy Giles, and Alan Streeter, and Larry Bloom … a dozen other politicians … were about to go down.

That’s next time on The City.

CREDITS

The City is a production of USA TODAY and is distributed in partnership with Wondery.

You can subscribe to the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you’re listening right now. If you like the show, please rate and review us, and be sure to tell your friends about us.

Our show was reported and produced by Wilson Sayre, Jenny Casas, and me, Robin Amer.

Our editor is Sam Greenspan. Ben Austen is our story consultant. Original music and mixing is by Hannis Brown.

Additional editing this week by Amy Pyle. Additional production by Taylor Maycan, Isobel Cockerell, Fil Corbitt, and Bianca Medious.

Chris Davis is our VP for investigations. Scott Stein is our VP of product. Our executive producer is Liz Nelson. The USA TODAY NETWORK’s president and publisher is Maribel Wadsworth.

Thank you to our sponsors for supporting the show. And special thanks to our attorneys Matt Topic and Tom Curley. And to Misha Euceph and Danielle Svetcov.

Additional support comes from the Fund for Investigative Journalism and the Social Justice News Nexus at Northwestern University.

If you like this show, you may like WBEZ’s new podcast, On Background, which takes you inside the smoke-filled back rooms of Chicago and Illinois government to better understand the people, places, and forces shaping today’s politics.

I’m Robin Amer. You can find us on Facebook and Twitter @thecitypod. Or visit our website, where you can read transcripts of John Christopher’s secret FBI tapes and more.

That’s thecitypodcast.com

PEOPLE

READ MORE

FBI informant John Christopher met with then-37th Ward Alderman Percy Giles and political consultant James Blassingame at Edna’s, a West Side soul food restaurant, on Jan. 18, 1995. Christopher secretly recorded the lunch as part of Operation Silver Shovel.

The City obtained transcripts of his tapes from the federal courts and later sued the FBI to obtain the original recording. In these excerpts of the transcript, John Christopher offers Percy Giles advice about dumping…

…and John Christopher gives Giles a $5,000 payment. Giles and Blassingame would later be convicted on corruption charges.