S1: Episode 7

The Takedown

A reporter scoops the FBI. Politicians get taken down in “Mount Henry’s” shadow. The six-story debris pile remains.

Episode | Transcript

The Takedown

Robin Amer: On January 10, 1996, people around the country turned on the radio and heard a story about a dozen public officials accused of taking bribes.

Robert Siegel, NPR anchor: In Chicago today, federal officials announced charges in what they call Operation Silver Shovel, a wide-ranging probe of public corruption.

Robin Amer: Reports noted that the three-and-a-half-year undercover investigation had first focused on illegal dumping but had expanded to include a lot of other things.

Cheryl Corley, NPR reporter: US Attorney Jim Burns says since that time the FBI’s inquiry has grown to include an investigation into cocaine trafficking, organized crime, and public corruption in Chicago’s surrounding suburbs.

Robin Amer: The story also introduced America to the informant at the center of this investigation: John Christopher. A man with an extensive criminal record, who had bribed a Chicago alderman and used his help to dump six stories of debris in the middle of a West Side neighborhood.

Cheryl Corley: Residents there call the large and unsightly dump site “the Mountain,” and they accuse the federal government of allowing Christopher to continue dumping in poor and minority neighborhoods while using him to target public officials. U.S. Attorney Burns denies the charge.

Robin Amer: By the time it wrapped, the FBI would call Operation Silver Shovel one of the most successful corruption probes in Chicago history.

With John Christopher’s help, the feds had gone after more than 40 people, and had convicted close to half. By using John Christopher to launder millions of dollars in old mob cash, they had hit the Outfit—the Chicago mafia—where it hurt. They’d even folded in a drug bust along the way.

But the investigation did not play out in Chicago’s neighborhoods the way it played out on the nightly news. In North Lawndale and places where aldermen had been targets, people felt betrayed—not just by their elected officials, but by the investigation itself.

Although Operation Silver Shovel took down corrupt politicians, it left “the Mountain” standing.

I’m Robin Amer. From USA TODAY, this is The City.

ACT 1

Robin Amer: Let’s rewind a bit, to January 5, 1996—before Operation Silver Shovel became a national story.

The covert part of the investigation was drawing to a close. For months, the FBI and the US Attorney’s office had been planning what they called “the takedown”—a highly orchestrated deployment of federal agents into the field.

They would interrogate more than 40 targets, including seven Chicago aldermen, three officials from the water treatment agency and two city inspectors. They would question every target at the exact same time.

This way, no one subject could warn any other subject to hush up, or destroy evidence, or get a lawyer.

Scott Lassar was second-in-command among Chicago’s federal prosecutors. The plan was to launch the takedown the following week—after Lassar's boss returned from vacation.

But then, Scott Lassar got an unexpected call.

Scott Lassar: She knew every detail about the investigation.

Robin Amer: The call came from a TV reporter named Carol Marin, who knew all about their targets and about their mole, John Christopher.

Scott Lassar: She wasn't calling to find out anything. She was just giving us notice.

Carol Marin: I called the US Attorney's office and said, “We’re about to break a story about an investigation that we know you have completed.”

Robin Amer: This is Carol Marin. She’s something of a legend in Chicago. She had previously covered operations Gambat and Greylord—the federal corruption probes that seemed to be almost an annual occurrence in Chicago. She’d been tipped off about this story by a reliable source.

Carol Marin: Somebody whispered in my ear, “You need to start looking at Jesse Evans, Ambrosio Medrano, and Larry Bloom...”

Robin Amer: All Chicago aldermen the FBI had been investigating...

Carol Marin: “...because there is this guy John Christopher who is fly dumping all over the city and paying people off.”

Robin Amer: John Christopher had been dumping in North Lawndale for almost six years. But now that it was tied to a city-wide corruption scandal, NBC couldn't wait to break the story.

Carol Marin knew Chicago was what the feds liked to call a “target-rich environment” full of corrupt officials. But she was surprised by who the feds had targeted. Aldermen like Jesse Evans and Ambrosio Medrano were not on her radar.

Carol Marin: There were people in City Council we knew were the ones we really wanted to watch, and those two weren’t.

And Larry Bloom, the white, South Side alderman who we met in the last episode. Well, this news did not square with his reputation.

Carol Marin: He was the pillar of rectitude. Sanctimonious, often. But he was the reformer.

Robin Amer: So, she knew this would a big story.

Carol Marin’s call set off a panic inside the US Attorney’s office.

Scott Lassar: She said that at that five o'clock news that night she was going to go with the story.

Robin Amer: Because the takedown was scheduled for the following week, airing the story that same day would have royally messed up their plans.

So, Scott Lassar asks if he and the head of the criminal division can come over to NBC and meet with Carol Marin and her produce like, now.

Carol Marin: Never before and not since has that kind of request ever come from a US Attorney's office to me as a reporter.

Robin Amer: So, what did you think when they made that request?

Carol Marin: It was further confirmation that we knew what we were talking about. They were over at NBC in record time. And they said, “Could you hold it until we raid Larry Bloom’s office and the other aldermen's offices?”

Scott Lassar: So we could have a chance to send the teams out to interview people.

Carol Marin: And we thought about that, because they were concerned about the destruction of materials.

Robin Amer: Carol Marin knew that one of her competitors at ABC had also been sniffing around this story. She was worried he would beat her to it.

But she took seriously the fear that aldermen might destroy evidence. She wanted to report on the investigation, but she did not want to get in its way.

Carol Marin: And so, we sort of carefully agreed.

Robin Amer: And the feds scrambled to do the takedown that same day.

* * *

Robin Amer: At this point, Scott Lassar passes the baton to FBI Special Agent Jim Davis. He’d been John Christopher’s day-to-day handler, and now he was effectively running the takedown.

Lassar’s office calls Jim Davis and tells him, "It’s go time. Forget next week. The takedown is on, now, today, pronto.”

So, Jim Davis springs into action.

Jim Davis: We set up, you know, kind of a command post.

Robin Amer: The command post is in a conference room in the federal building downtown. The room is full of telephones. The walls are lined with butcher block paper the agents will use to track their targets. Jim Davis is stationed there, at the center of things, because he knows the case better than anyone. Four or five other agents are there too, to help him man the phones and manage the teams in the field.

Jim Davis: And from that command post we were we issued an “execute” order. We told them all to go at the same time and then we just waited for results.

Robin Amer: More than 100 federal agents fan out across the city. One team goes to the Southwest Side, to Alderman Ray Frias. Another goes to the West Side, to Alderman Percy Giles, and so on.

Jim Davis: We had teams that were out doing search warrants. But the most focus was on the actual interview teams of guys that were going out and interviewing subjects.

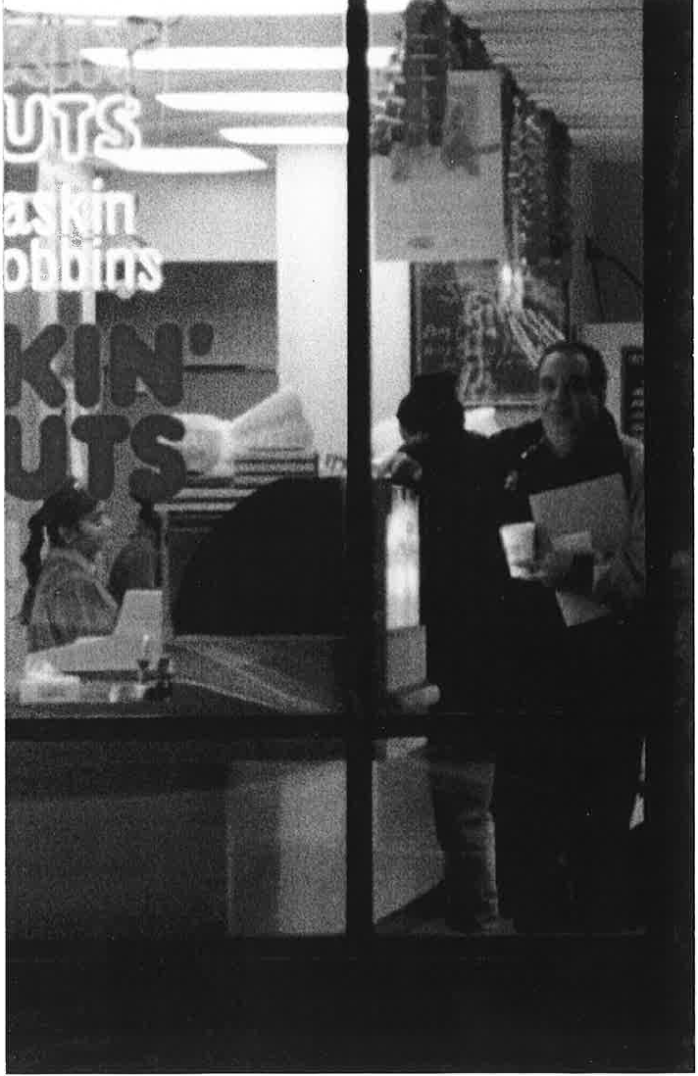

Robin Amer: Each of these interview teams takes along a photograph of John Christopher. We got a copy of it from the US Attorney’s office.

The photo shows John Christopher standing inside a Dunkin’ Donuts. He’s holding a cup of coffee, and there’s a folder of papers tucked under his arm. The photo was taken from outside the coffee shop, because it’s supposed to look like a surveillance photo.

Jim Davis: I think that there was a Dunkin’ Donuts at Plymouth and Jackson or somewhere right there by the by the office, and I think—

Robin Amer: I knew it! I was like, I think that's the Dunkin’ Donuts right across from the Federal Building.

Jim Davis: Right. I think that’s right.

Robin Amer: But the photo was staged.

The FBI’s interview teams show this photo to their targets, and ask them, “Do you know this man?”

Of course, the FBI knew the answer was yes; they’d been investigating these guys for years and all of their targets definitely knew John Christopher. But even if their targets lied and said, “No, I don’t know this guy,” even that was helpful.

Jim Davis: By them lying about their relationship with John Christopher, for example, it would show that they know that there's some reason for them to lie about that relationship. It shows that that they have some understanding that it is a corrupt relationship.

Robin Amer: Each team also had a video player loaded with audio or video footage of John Christopher and the target.

So, if an alderman denied knowing John Christopher, the FBI agents would pull out the video player, play the footage, and ask, “If you don’t know John Christopher, then why are you on this video taking money from him?”

In the command center, Jim Davis started to hear back from the field teams. And it quickly became clear, that, from a law enforcement perspective, this takedown was going better than anyone had predicted.

Jim Davis: We had multiple confessions that came that were being reported back to us in the command post, which was really surprising. We didn't expect it.

Robin Amer: One of their targets was Tom Fuller, an official at the city’s water treatment agency. John Christopher had been bribing him for years, even before the investigation started.

The FBI agent responsible for questioning Fuller was Tony D'Angelo, who we heard from in Episode 5. Remember, he told us about his meetings with John Christopher at the Pizza Hut in Cicero.

Jim Davis says that he was surprised when Tony D'Angelo called in right away.

Jim Davis: He was clearly sitting with Tom Fuller when he made the conversation, and he says, “Hey Jim, I'm sitting here with Tom. You know, he'd like to come in and talk to you and work this thing out.” And he was, you know, a little cryptic in what he was saying. So, I said, “Tony, did he confess?” And he says, “Oh, yeah. Yeah.”

And I said, “Well, you know, bring them in.” So, Tom Fuller came in with Tony D'Angelo. And we took him into one of the interview rooms there in the FBI office and interviewed him about his contact with John Christopher and he confessed again.

And I think that these guys were so stunned to learn that John was working with us that they just figured they had nowhere to go.

Robin Amer: Percy Giles was at his West Side office when the FBI showed up. He’s the alderman we met in the last episode, having lunch at Edna’s and taking money from John Christopher.

Percy Giles: And they asked me, did I know John Christopher? And I think at first, I might have told him no, because it didn't dawn on me. Then later I said, “Yeah, I do know him.”

Robin Amer: He says it took him awhile to realize what was happening.

Percy Giles: I knew it wasn't good. And I remember asking them, “Do I need a lawyer?” And they told me, “You might.” When I went home that night, and I remember I was nervous—so nervous when I was telling my wife about it, I remember my knees just fell from under me. I almost fell to the floor.

Robin Amer: With the takedown underway, federal prosecutor Scott Lassar went over to City Hall. He was there to pay Mayor Richard M. Daley a courtesy call. He wanted to let the mayor know that, at this very moment, seven aldermen and a mess of other city officials were being questioned by the FBI. Lassar didn’t want the mayor to find out on the 10 o’clock news.

And according to Lassar, Mayor Daley was not interested.

Scott Lassar: He asked no questions, and then he started discussing the legislature had recently given him power over the Chicago Public Schools, and he told us about what his plans were for the Chicago Public Schools.

Robin Amer: Lassar could not understand how the city’s chief executive could be so uninterested in a massive corruption scandal that had happened on his watch.

If Mayor Daley was afraid of the potential fallout, he didn’t show it.

Scott Lassar: He certainly didn't fear federal law enforcement or have personal concerns about federal law enforcement. But I would have thought he would have asked some questions and he had no interest whatsoever.

Robin Amer: We reached out to former Mayor Daley for comment, but he never responded.

Meanwhile, about 15 miles south of City Hall, TV reporter Carol Marin was waiting for the go signal from the feds.

Carol Marin: I was on the phone with Scott Lassar, I think, every hour or every other hour, just to make sure that there wasn't a call coming to them from another competitor, because we were really were ready to go.

Robin Amer: Because Carol Marin knew that the takedown was happening that day, and because she’d agreed to hold her story, she could now get everything on tape.

Carol Marin: I and a camera crew stood outside Larry Bloom's office and waited for the FBI in sort of, “V” formation, to go in and do their raid.

Robin Amer: Larry Bloom had started his day at his South Shore law office when two FBI agents showed up and asked to talk to him.

They asked him if he knew John Christopher. He said yes. So, they asked him some more questions.

Larry Bloom: Eventually my tentacles rose up, and I said, wait a minute. There's something strange going on here. They seem to be wanting to accuse me of something. And so, I immediately went down the hall and talked to a lawyer in our suite who did criminal defense work. He came in, identified himself, and said that I was no longer answering any questions.

Robin Amer: Carol Marin’s crew caught on camera what happened next.

Carol Marin: Larry Bloom was running from his office, looking as though he was about to be sick, and saw me and wasn't pleased and ran into the bathroom.

Larry Bloom: I hate to admit this. I really had to go to the bathroom (laughs) because you know what happens when you're tense. And so, I was running out the front door and there's Carol Marin with her camera crew.

And I remember exactly what I said to her. I said, “Just be professional,” or something like, “I expect you to handle this professionally.”

Robin Amer: He suspected the feds had tipped her off to try to sway public opinion against him. And that made him furious.

Larry Bloom: Someone had told her that the FBI is going to be going to Bloom's office, and you might want to be there, which I think is an abuse of the federal prosecutor's power to try to sway the jury or the general public on a particular case where they're involved.

Uh, anyway, I made it to the bathroom. (laughs)

Robin Amer: Finally, with this footage in hand, Carol Marin has a huge scoop for that night’s news.

And the story explodes. Over the next few days, reporters swarm the lobby of City Hall, trying to figure out who else the FBI has been investigating and get them on tape.

Most won’t answer questions and deny having done anything wrong. Like Percy Giles, the alderman who had fallen to his knees when he realized he was under investigation.

Percy Giles: I haven't been charged with anything and I have done nothing wrong. And um and I will respond to any question at the proper time.

Robin Amer: And Ray Frias. He’s the one who said that being a politician was all about “making money.”

Reporter: Have you ever met with John Christopher?

Ray Frias: Again, John, I'm not going to answer any questions that pertaining to the investigation.

Robin Amer: Virgil Jones, who had accepted $4,000 wrapped in a newspaper, admits that yeah, he knows John Christopher.

Virgil Jones: He donated some ah, watermelons one time to one of my ah, picnics. But not with my knowledge. He drove up with a truck full of watermelons and uh, I was across the street and he started giving them out. They asked me if he'd given me any money. I told him they had to talk to my lawyer.

Reporter: Did he give you any money?

Virgil Jones: I make no comment about that at this time.

Robin Amer: But one alderman calls a press conference. Ambrosio Medrano had taken $31,000 in bribes from John Christopher and had introduced him to other aldermen. Medrano confesses and publicly apologizes and continues to apologize again and again.

Ambrosio Medrano: You know, I don't think that whenever anybody does anything wrong, they really know why. Um, I don't know, to be honest with you.

Reporter: This guy was a smooth operator, wasn't he?

Ambrosio Medrano: Yes, he was. I can tell you that from the initial meeting that I had with him, and the first time that I actually met with him and accepted the money, had been several months. I mean, he had called me and badgered me, and called me and asks me, asked me to meet with him, and I refused. Why I finally gave in, I don't know. And that was the mistake I made. I accept total responsibility for what I did.

Robin Amer: Jim Davis recalls leaving the office at midnight the night of the takedown, pleased with how smoothly everything had gone despite how rushed they had been.

Jim Davis: So, if you start out the day with us having to spring this early because it had been compromised somehow by a reporter. And then, you know, it ends up with us getting a bunch of confessions that we really didn't expect. It was just a, it was a good day. Was a really good day.

Robin Amer: Over the next three years, federal prosecutors indicted a dozen city officials.

Only Ray Frias was fully acquitted. Larry Bloom pled to a much less serious charge of tax evasion and was sentenced to just six months in prison. One of the water commissioners was also convicted on lesser charges.

Ambrosio Medrano—the one who apologized—would go to prison, get out, run for elected office again, and then go back to prison a second time on new corruption charges. The other officials either pled guilty to corruption charges or were convicted of the same.

Here’s prosecutor Scott Lassar in March of 2000.

Scott Lassar: Looking back on everything, I still think this is one of the the most successful political corruption investigations ever conducted in Chicago.

Robin Amer: And yet, the feds also took a lot of heat for this case.

Even with their explanation about the mechanics of the investigation, where one alderman had introduced them to another and another, the optics of having pursued almost only black and Latino politicians were very bad for them.

The feds were also criticized for using a guy like John Christopher as their informant—a guy who had defrauded the city and the federal government, who had been bribing elected officials his whole adult life, who was tied to the mob, and who prosecutors say wanted to murder a federal witness.

It did not endear the feds to the public—or to Milton Shadur, the federal judge who presided over Larry Bloom’s case.

During the sentencing hearing, Judge Shadur excoriated the feds, saying, “It is quite distressing to find in this case the United States having enlisted to its aid the villainous John Christopher. … Having somebody of this stripe as a weapon of law enforcement denigrates the system in a material way. … It is true of law enforcement agencies, as it is of anyone else, that if you lie down with dogs you are likely to get up with fleas.”

But there was one other gigantic problem with Operation Silver Shovel.

As the feds executed their takedown—as they busted elected officials and confronted them with their misdeeds, as they prepped for trial and talked to the press—they did nothing about the six stories of construction debris in North Lawndale.

By the day of the takedown, John Christopher’s illegal dumps had loomed over the neighborhood for nearly six years.

But the FBI and the US Attorney’s office had no intention of removing what the agency commonly referred to as “Mount Henry.”

Jim Davis: I don't think that we had any obligation to clean up “Mount Henry” or the other one that he had, because, first of all, that's not what we do, and we didn't create it. I mean, there are agencies that are responsible for cleaning up stuff like that.

Robin Amer: But giving John Christopher cover had made the problem worse for all the people who had been fighting him.

That’s after the break.

ACT 2

Robin Amer: The six years prior to the takedown were frustrating ones for Henry Henderson, head of Chicago’s Department of Environment. His many attempts to stop John Christopher from dumping in North Lawndale had failed, one after another. And his good friend, federal prosecutor Scott Lassar, had rejected his calls for help.

Henderson had asked Lassar and the US Department of Justice to look into what he believed was a criminal conspiracy to dump in Chicago neighborhoods. Lassar had dismissed this as a municipal waste problem.

On the day of the takedown, Henry Henderson was at work in his downtown office. He didn’t yet know about the federal probe.

As he walks down the hallway, he looks into a conference room and sees one of his field inspectors talking to an FBI agent.

And Henderson, seeing this federal law enforcement agent, flashes back to his conversation with Scott Lassar. He thinks, Finally! The Department of Justice must have sent the FBI to help.

Henry Henderson: And I said, “FBI agent, thank God you're here. We really need federal help on this thing.”

And he goes, “Do you know this person?” Shows me pictures.

“Yeah, that's John Christopher.”

“Have you talked to Mr. Christopher?”

“Yes, I've talked to Mr. Christopher.” And I said, “I'm so glad you're after him.”

So, I thought they were talking to the inspector in order to get a better fix on how to stop this problem.

Robin Amer: But the FBI agent in the conference room was not there to help Henderson's inspector. He was there to interrogate the inspector.

Henry Henderson: I had no idea what he was doing was showing tapes related to him taking money. They had a case of official corruption against somebody who was working in the department.

Robin Amer: This inspector was one of the targets of Operation Silver Shovel. Instead of issuing citations for illegal dumping—instead of fighting John Christopher—Henry Henderson’s inspector was taking bribes from John Christopher.

He was one of two environmental inspectors who would eventually be convicted on corruption charges.

Henry Henderson: Well, I was shocked. I was shocked.

Robin Amer: And as all this starts to sink in, Henry Henderson recalls all the conversations he’d had with his inspectors ever since the city’s civil lawsuit against John Christopher was resolved in their favor.

A judge had ordered John Christopher to clean up the Mountain in North Lawndale, but according to Henderson’s inspectors, he had instead “disappeared.”

Henry Henderson: And they said, “We haven't seen him.” But they, it turns out, they had seen him. And that was in the course of when they apparently took some money.

Robin Amer: So, was their failure to cite these dumps properly because they were being bribed one factor that allowed these dumps to get as bad as they did?

Henry Henderson: Obviously. I mean if you've got people out there who are in the business of enforcing the law and they are not enforcing the law, this is a big problem.

Robin Amer: Later that day, Henderson learns about the raid at Larry Bloom’s office. And he learns that John Christopher is an FBI mole.

Now he’s reeling. A conversation he’d had with Bloom the previous year suddenly makes sense.

Henry Henderson: I had an interesting and surprising visit from former Alderman Larry Bloom, who came to see me about getting permits for recycling concrete debris and doing a “rock-crushing activity.”

Robin Amer: Remember, Bloom was the alderman who had helped John Christopher find a lot for his phantom rock crusher. And Henderson had tried to warn Bloom: You do not want something like this in your ward.

Henry Henderson: And I said, you know, “Look at what has happened on West Side, particularly 24th Ward, with John Christopher's site. And what you're describing is remarkably similar to the way John Christopher describes things. And I think it's something you need to be very careful about and aware of.”

Robin Amer: And what did Larry Bloom say when you gave him this advice?

Henry Henderson: He said, “I would never deal with anybody like John Christopher.”

Robin Amer: Larry Bloom told us that he does not recall denying that he knew John Christopher.

But with the news of the takedown, Henry Henderson finally understood why he could not get the feds to help him. They were protecting their investigation and keeping their star informant in play.

* * *

Robin Amer: The next morning, news of Operation Silver Shovel was splashed across the papers and started to reach residents in North Lawndale.

Jenny Casas: Alright, so, where are we? We're on Kostner and 16th?

Cecil Reddit: We're on Kostner and 16th. This is where the newsstand was.

Robin Amer: Our producer Jenny Casas spoke with lifetime North Lawndale resident Cecil Reddit. His family owned and operated a newsstand just four blocks from the dumps. The newsstand is gone now, but that day was one of the busiest he can remember.

Cecil Reddit: I mean, we did a lot of sales on that. I mean, we get the papers dropped off at 4 o’clock in the morning. When that happened, about six, seven o'clock, we were out of papers. I'm talking about a thousand newspapers.

Jenny Casas: Six or seven o'clock in the morning?

Cecil Reddit: A thousand newspapers gone.

Robin Amer: Silver Shovel was the talk of the newsstand, as politician after politician got swept up in the probe.

Cecil Reddit: A lot of people was like, there's a lot of people going to jail, and they will talk about, “Hey, man,” you know, “Did you see who?” You know, because they knew some of the individuals that was involved. So they was like, “Man, this is, you know, this is such and such, did you see him? He was involved, man.” “He was involved?” You know, “I didn’t know he was involved in that.”

Robin Amer: The dumps less than a mile away had been the talk of the newsstand before—they had been there for years. But this time was different. For the first time, they were also front-page news.

Cecil Reddit: So, we really got deep in the conversation then. We became philosophers then. You know, how someone can just dump in our neighborhood and get away with it? You know, and honestly, we said to ourselves, there's no way that this would happen in the Caucasian neighborhood.

Robin Amer: Running the newsstand over the years, Cecil Reddit’s father had seen his share of Chicago’s corruption scandals.

Jenny Casas: So, what did your parents think about operation Silver Shovel when they heard about it?

Cecil Reddit: My dad just shook his head and said, “Man, you never know who.” And he said, “Money will change you in a way. Be careful, son. Don't never let that money change you.”

Robin Amer: North Lawndale residents who’d been fighting John Christopher for the past six years found it shocking and surreal to suddenly learn that he was working for the FBI.

Gladys Woodson: “What's Silver Shovel?” That was my first thing. “What is Silver Shovel?” And they said, “Oh you—the dump site.”

Robin Amer: This is Gladys Woodson, the block club president who had confronted John Christopher at the vacant lot. She realized that in this investigation, she and her neighbors were collateral. They had been used. They were never able to get traction fighting John Christopher, and now they could see why.

Gladys Woodson: He had to have backing, you know, 'cause the people that we was contacting and seemed to, you know, was pushing it under the rug or not answering.

Robin Amer: For everyone in North Lawndale whose children had been hurt, whose property had been damaged, whose neighborhood had been disrespected, this was a huge breach of trust.

As Ms. Woodson once put it:

Gladys Woodson: We wrote to everyone from who’s who to who’s that.

Robin Amer: And no level of government, not the city, not the state, not the feds, had ever fixed the problem.

Now the FBI was crowing over the results of its investigation. Chicago and the nation were captivated by the news of this mob-connected guy turned FBI mole. But in North Lawndale, the announcement just felt like a punch in the gut.

Last spring, we caught up with Rita and Michelle Ashford, the mother-daughter duo who had protested the dumps, marching in the streets with signs that read “Down with John” and “Dump the dumps.”

All these years later, they still remember where they were when they heard the news about Operation Silver Shovel. Here’s Michelle.

Michelle Ashford: We were at home and it broke on the news, and then we started calling everybody. “This is about the dump right here” and all this.

Robin Amer: Her mom, Rita Ashford, was also stunned. John Christopher had turned her block into a mountain of hazardous debris. Her grandchildren and her neighbor’s kids had suffered from severe asthma, made worse by the dust from the dumps.

And now it turned out that John Christopher had actually been working with the FBI?!

Rita Ashford: I never—when they said about him being a mole, I was shocked. Because that's something that we never even anticipated. We just figured that John Christopher had that cem—that concrete, pile there. He was making money off of it and that's the purpose of it. And that's what we thought. We knew it wasn't healthy. But at that point, that's that's all we ever thought.

Robin Amer: Like Ms. Woodson, they came to believe that this was why no one in government had ever effectively dealt with the dumps.

Michelle Ashford: Oh, that's why we couldn't get any help.

Rita Ashford: Right.

Michelle Ashford: That's why we couldn't get any help with it. Because everything was like, oh so they knew all this was going on all along before we even begin to fight for it. And and the reason why we couldn't get any justice for anything because it was all the government. And they knew it from the very beginning.

Robin Amer: The news seemed to confirm what they’d been saying for years about the government’s neglect of their neighborhood.

Rita Ashford: I’ma tell you something: I was angry as hell. Because once again, we the underdog. And the sad thing about it was, it was a serious thing where it affected people's health. John didn't have to be allowed to still do have that dump, because you had ammunition to use against him.

Robin Amer: There was also the question of what would happen to John Christopher now. Would he ever be held accountable for what he’d done in North Lawndale?

That’s after the break.

ACT 3

Robin Amer: Even though John Christopher had agreed to wear a wire and had become the centerpiece of a major undercover investigation, his participation in Operation Silver Shovel was not a get-out-of-jail-free card. He did not have a deal for full immunity.

So, FBI agent Jim Davis warned John Christopher not to do anything illegal that wasn’t part of the investigation.

Jim Davis: And I would just try and reassure him and say, “Look if you're straight with us, you know, if you continue to do what we're asking you to do, if, you know, if you stay out of trouble, you're going to be OK.”

Robin Amer: But John Christopher did not hold up his end of the bargain. Even while cooperating, he committed crimes and went behind the bureau’s back in other ways.

As Silver Shovel was underway, the FBI’s organized crime squad was also looking into an illegal gambling operation in Chicago’s western suburbs, run by an alleged mob boss named Tony Centracchio.

Jim Davis: You know, John referred to him as his “Uncle Tony,” and that was a problem for me, because we had a wire on Uncle Tony.

Robin Amer: The wire was a video camera hidden in the ceiling of Tony Centracchio’s office.

Jim Davis: And every time John went into see him, we were recording.

Robin Amer: It’s not totally clear what John Christopher was doing there. He was never charged in the illegal gambling case. But him showing up on another investigation’s wire made things complicated for Jim Davis and his fellow agents.

Jim Davis: I would have liked to have said, “John, stay away from Uncle Tony's office,” but I can't tell John that we have a wire on Uncle Tony's office.

Robin Amer: In addition to that, John Christopher also neglected to file his federal income tax returns in 1992 and 1993. I know. It seems so mundane.

But he also committed bankruptcy fraud through one of the sham construction companies he’d set up during Silver Shovel. And ultimately, bankruptcy fraud and tax evasion were what sent him back to prison.

Not illegal dumping or any of the other things he’d done before he started cooperating, like bribing Bill Henry. We got a copy of his plea deal, and the federal government chose not to charge him for any of that.

Ultimately, John Christopher is sentenced to 39 months in federal prison. At sentencing, he told the judge, “I’m sorry for the things I did in my past life.”

But he would never be forced to clean up the dumps or provide restitution to anyone in North Lawndale.

And then, after he got out of prison, he really would disappear—maybe for good this time.

* * *

Robin Amer: I’ve been looking for John Christopher for almost three years, trying to figure out what happened to him after he got out of prison.

In his plea deal, the feds explained that because he had cooperated with the FBI and worn a wire against the mob, he could not safely return to his old life—or even be in Chicago without FBI protection.

So, I looked for John Christopher everywhere I could think of: every public database, every government agency that might have a lead. I found nothing.

Then, in March, our reporter Wilson Sayre got a phone call.

Wilson Sayre: So, I was reading Illinois EPA remediation reports, and I get a call from a random number, which is not unusual. And I pick it up, and on the other line is somebody asking me why we're reporting on Silver Shovel again.

Robin Amer: The man on the phone was a lawyer calling on behalf of his client: Angelo Christopher. John Christopher’s older brother.

Wilson Sayre: I have contacted nobody within the John Christopher family, and so it takes me a while to figure out that someone has called Angelo, and said, “There are these reporters. They're doing something about Silver Shovel. You need to maybe call this person,” but gave Angelo my number and Angelo calls his lawyer. He essentially was like, “I sort of respect your desire to look into this story but know that there are consequences for the people who are involved. Like, this is garbage, and why are you digging up old garbage?” And John Christopher’s brother Angelo does not want to talk.

Robin Amer: And it sounded like he was pretty emphatic on that point. Can you—

Wilson Sayre: Yes, very emphatic. “Absolutely not,” is what he said.

Robin Amer: Eventually, I learn that when John Christopher got out of prison, the FBI set him up with a new name, a new social security number and a new life. And that there’s an FBI agent in St. Louis who might have that information.

I ask if he’ll talk to me, or if not, if he’ll pass a message to John Christopher. This was the response I got from the FBI’s public information officer:

Rebecca Wu: Hi Robin, it’s Rebecca Wu at the FBI in St. Louis. I spoke with the agent, and he says he appreciates your sympathy for the source, but not surprisingly he declines to participate. Again, he says that it’s his responsibility to protect his source, and he says that he hopes that you understand that. So, thank you very much and let me know if you have any other questions. (Sound of phone hanging up)

Robin Amer: Even after all this time, it seems the FBI is still protecting John Christopher.

Over the last seven episodes, we’ve told you a story about Chicago—a city infamous for corruption and racial divides. But this problem is not unique to this city.

Our story in Chicago is not over yet. But to understand what happened here, after John Christopher disappeared again, we have to take a side trip to Houston, a city where black neighborhoods have been fighting their own battles against their own mountains for a very long time.

Robert Bullard: And I would tell my students, I’d say, “If you see a mountain in Houston—Houston is flat, lots of it is below sea level—if you see a mountain in Houston, be suspicious. Landfill!

Robin Amer: That’s next time on The City.

CREDITS

The City is a production of USA TODAY and is distributed in partnership with Wondery.

You can subscribe to the show on Apple Podcasts or wherever you’re listening right now. If you like the show, please rate and review us, and be sure to tell your friends about us.

Our show was reported and produced by Wilson Sayre, Jenny Casas, and me, Robin Amer.

Our editor is Sam Greenspan. Ben Austen is our story consultant. Original music and mixing is by Hannis Brown. Additional editing this week by Amy Pyle and Matt Doig. Legal review by Tom Curley.

Additional production by Taylor Maycan, Fil Corbitt, Isobel Cockerell, and Bianca Medious.

Chris Davis is our VP for investigations. Scott Stein is our VP of product. Our executive producer is Liz Nelson. And the USA TODAY NETWORK’s president and publisher is Maribel Wadsworth.

Thank you to our sponsors for supporting the show. And special thanks this week to Kevin Blair, Don Mosley, Misha Euceph, and Danielle Svetcov.

Archival audio courtesy of NPR and WBBM Newsradio 780 and 105 point 9 FM.

Additional support comes from the Fund for Investigative Journalism and the Social Justice News Nexus at Northwestern University.

If you like this show, you may also like WBEZ’s new podcast On Background, which takes you inside the smoke-filled back rooms of Chicago and Illinois government to better understand the people, places, and forces shaping today’s politics.

I’m Robin Amer. You can find us on Facebook and Twitter @thecitypod. Or visit our website, where you can see the staged surveillance photo of John Christopher at the Dunkin’ Donuts and more.

That’s thecitypodcast.com

PEOPLE

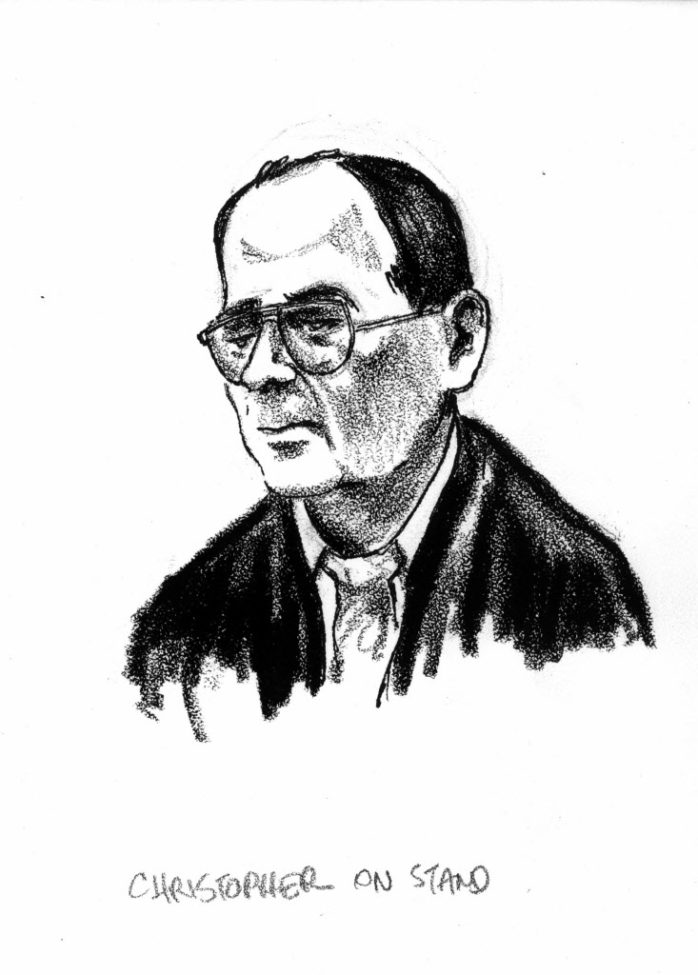

(Illustration by Verna Sadock Courtesy of the Chicago Sun-Times).

READ MORE