S1: Episode 8

Houston

An illegal dump in Chicago has seeds in a legal one in Houston. The numbers reveal an unsettling pattern. A movement takes root. The president gives an order.

Episode | Transcript

Houston

Robin Amer: Residents of Chicago’s North Lawndale neighborhood had spent the better part of six years fighting John Christopher’s pair of illegal dumps.

In talking with some of these residents, it was clear to them that this happened in their neighborhood because it was black neighborhood. It was not a coincidence. It was by design.

Michelle Ashford: So that just goes to show me what you think of black people, and poor black communities. We can put this here.

Conrad Henry: This ward? They didn't care. Twenty-fourth Ward was like a dumping ground for them.

Gladys Woodson: It just wouldn't happen in any other neighborhood, I don't think.

Jacquelyn Rodney: Anything can be done to black people. Anything.

Robin Amer: When a similar dump cropped up in a mostly white Chicago neighborhood, the one next to Lane Tech High School, city officials shut it down fast. And Operation Silver Shovel, the FBI’s carefully orchestrated investigation into public corruption, sprung from the North Lawndale dumps without factoring in a plan for a cleanup.

That’s our ongoing story in Chicago, a city notorious for public corruption and racial divisions.

But what we saw unfolding in North Lawndale is just a symptom of a much bigger problem—one that is not confined to Chicago.

Black and brown communities all over the country are disproportionately impacted by environmental hazards.

We know this, in part, because of a man named Robert Bullard.

Robert Bullard: My grandmother lived on the road where the city landfill was located. I remember this vividly. We would go there on Sundays. We’d go up there, and the landfill was a burning landfill. And we would go up there and play. We thought nothing about it.

Robin Amer: Bullard and his family are black. And even as a child growing up in Alabama in the 1950s and ‘60s, he noticed that dumps like the one near his grandmother’s house seemed to be located mostly in black neighborhoods.

Robert Bullard: I only later discovered that that was more than just a hunch.

Robin Amer: Bullard grew up to be a sociologist, and when he was teaching in Houston in the late 1970s, he got involved with a group of black homeowners fighting a landfill proposed for their neighborhood. And these Houston residents started saying the same kinds of thing you heard people in North Lawndale say in previous episodes: This is happening to us because we are black.

Only they were saying it roughly 20 years before the dumps sprang up in North Lawndale.

Bullard wondered: Could he find a way to prove this—and prove it beyond dispute?

Robert Bullard: It was very clear, and it didn’t take a rocket scientist or PhD to put the pieces together. But it did take a PhD and a lawsuit to connect the dots, unfortunately.

Robin Amer: Robert Bullard’s efforts to tie dumping to racial discrimination—first in black neighborhoods in Houston, and later in black and brown neighborhoods all across the country— started with magic markers, push pins, and paper maps.

From those humble beginnings, his work would help spark a movement. It gave this type of discrimination a name. And it would ultimately force officials at the highest levels of government to confront the kind of injustice that we’ve been telling you about in North Lawndale.

Robert Bullard: I never knew that we would stumble on something that nobody else had done.

Robin Amer: I’m Robin Amer, and from USA TODAY, this is The City.

ACT 1

Robin Amer: In our last episode, Operation Silver Shovel became front page news. Aldermen and other city officials went to prison. And the feds gave John Christopher a new life. But the six-story mountain of rubble in Chicago’s North Lawndale neighborhood was still there—and there was no plan to get rid of it.

In this episode, we’re going to hit pause on the Chicago story, because we want to zoom out and look at the big picture—whether the dumping in North Lawndale is indicative of a larger national problem.

So, we’re going to take a side trip a thousand miles south of Chicago, to Houston. And we’re going to go back to the 1970s, roughly 20 years before the first trucks dumped their first loads of debris in North Lawndale.

Earlier this year I went to Houston with our reporter, Wilson Sayre. She’s going to pick up the story from here.

Wilson Sayre: In 1971, Margaret and Charles Bean were representative of an emerging, black middle class in America. Charles worked at the Goodyear tire plant making artificial rubber, and was active in the union, making sure black workers had the same opportunities as their white colleagues. Margaret worked at a factory where they made little fruit pies.

She had grown up most of her life in Houston. He had grown up in the country but had always wanted more of a social life than the country had to offer. And now they had kids and had outgrown the apartment they got together after getting married.

The couple wanted to buy a home—the type of place where they could grow their family and raise children. A place to have barbecues in the backyard and chat with neighbors on walks.

Charles Bean heard about a neighborhood—Northwood Manor—that was being marketed to young black families like theirs.

Charles Bean: My brother was living out there. So, we moved out there for that reason, along with the advertisement on the radio stations. They were advertising that area.

Wilson Sayre: Houston is a huge, sprawling metropolis, and Northwood Manor is out on the city’s northeastern edge, where the suburbs give way to more rural surroundings.

The pine forests there had been cleared to build neat, one-story brick ranch homes, with carports and perfectly manicured lawns.

Charles Bean: I was very impressed with the model home that I saw. And my daughter Tangela was with me at that time, and I asked her, what did she think? ‘Course she liked it. And so we went and looked at it and we said, yes, we're gonna take this one right here.

Wilson Sayre: The house the Beans bought had pomegranate, peach, and plum trees in the front yard—it was their dream home.

Here’s Margaret:

Margaret Lair: Well, I was able to start my family there, raised my family. I was able to meet my neighbors and we often will go outside and talk. And so that's what made me love my neighborhood.

Wilson Sayre: Then in 1978, seven years after making Northwood Manor their home, one of Margaret’s neighbors mentioned to her that a company was clearing trees just down the street, right next to their neighborhood … in order to make room for a new landfill.

Margaret Lair: I was very, very surprised. I didn't think they would put that type of landfill a next to our high school. Our high school, Smiley High School, was on the side of the landfill.

Wilson Sayre: The fruit trees, the manicured lawns—everything that residents loved about living in Northwood Manor—would now be next to dirty diapers, rotten food, and all the garbage that other Houston residents wanted out of their homes. It would be hauled away and left next to Charles and Margaret Bean's home.

A disturbing thought nagged at Charles Bean and his neighbors—the same thought that would be shared 20 years later by North Lawndale’s residents: This is happening because this is a black neighborhood.

Charles Bean: I felt insulted. Yeah, and like, you get the idea that all the undesirable things is geared toward us, you know, railroad tracks, the waste treatment plant, everything that’s undesirable. You get the idea that that's what's concentrated in your neighborhood

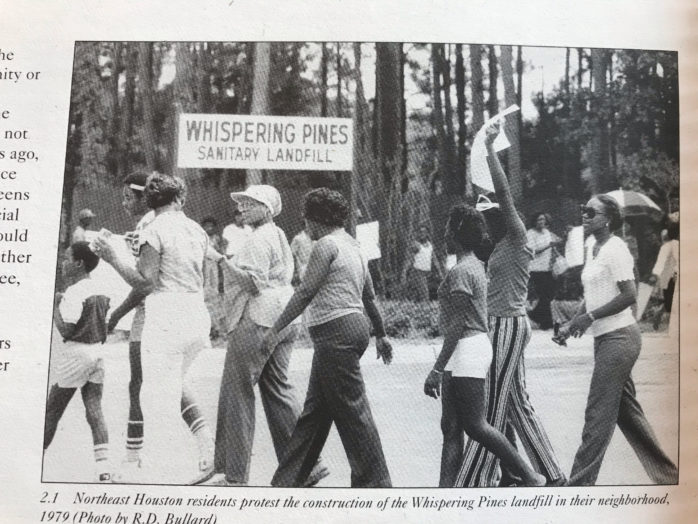

Wilson Sayre: Adding to the insult was that the company behind the landfill was marketing it to Northwood Manor’s residents as a “sanitary landfill” called “Whispering Pines”—a term and a name that evoked something lovely, sweet smelling, and hushed. The residents knew it would be anything but.

Charles Bean: If you think about the name “Whispering Pines,” see, that sounds pretty good. And if you're not mindful of what's actually going on there, then you probably would think that it was clean, like sanitary. It was everything but sanitary.

Wilson Sayre: Just like the families in North Lawndale who saw a dump rise up in their neighborhood across from Sumner Elementary School, the residents in Houston’s Northwood Manor worried about the smell, and the trucks, and the negative impact the dump would have on their property values.

That wasn’t what the Beans wanted for their neighborhood. So, they started to rally their neighbors to fight the dump.

Margaret Lair: We went from door to door knocking, to give out leaflets, to let our neighbors know what they're proposing to do.

Wilson Sayre: They organized meetings at the True Light Missionary Baptist Church and the Barbara Jordan Community Center to figure out how to fight the dump.

Pat Reaux: Margaret was going around, and they had a bullhorn, and they was telling residents and passing out flyers.

Wilson Sayre: This is Pat Reaux, one of Margaret and Charles Bean’s neighbors. They’re best friends now, and they met during this fight.

Pat Reaux: They said, “Do you know that we're having a meeting tonight? And they're putting a landfill next door.” I'm talking about, “Next door where?” That was unheard of, because all you had then was a wooded area. You could throw a rock and land it in the landfill from where we were. So that really got a lot of people riled up, because they're just buying homes and all this good stuff.

Wilson Sayre: The news that a landfill was coming to her neighborhood was incredibly distressing for Ms. Reaux. She knew exactly how awful living next to a landfill could be.

When she was a kid, she grew up on a street that dead-ended by another dump. This was in another predominantly black neighborhood in Houston.

Pat Reaux: And we used to have so much trash and stuff, and see these big mounds. But the worst thing was the rodents and the stray animals that it brought. The stench was unbearable.

Wilson Sayre: The dump attracted so many animals that ran through their yard, her dad had to set out raccoon traps. She said neighbors would sometimes come by to watch cats battle the dump’s rats.

Pat Reaux: I mean some of my neighbors would actually sit there and bet if the cats was gonna win the fight. And in some cases, baby, those rats were bigger than the cats. Bigger. That was a horrible life for a teenager. But you know, we lived it until he said, “No more.”

Wilson Sayre: Her family just walked away from that house. Abandoned it.

That was her childhood. And here she was, a new mother herself, in a new house, confronting the idea that her own children would also grow up next to a dump. She was not going to let that happen.

Pat Reaux: Yeah, we took over. We didn’t get involved, we took over.

Wilson Sayre: Pat Reaux joined the Beans and several other neighbors to form a neighborhood alliance.

The plan: To file a lawsuit against the private company building the landfill and convince a judge to issue an injunction. That would stop the dump before it could ever get started—before that first pile of rotting garbage could be trucked into their neighborhood.

Charles Bean: We wanted to stop it in its tracks, and they were trying to build it as fast as they could.

Wilson Sayre: So, the group hired an attorney named Linda Bullard, and she filed a lawsuit in county court in October of 1979. The crux of their legal argument was that putting the dump in a predominantly black community amounted to racial discrimination.

But how do you prove this kind of discrimination in a court of law? Where’s the concrete evidence that one dump in one black neighborhood is the sort of racial injustice that requires a judge to make things right?

Linda Bullard declined our invitation to talk about this case. But we spoke to her ex-husband, Dr. Robert Bullard.

And Dr. Bullard was the one who wound up wrestling with these questions about proof.

The way Dr. Bullard tells it, his wife walked in one day with an unexpected piece of news.

Robert Bullard: She came home and said, “Bob, I've filed a lawsuit against the state of Texas.” And I said, “You did what? You sued Texas?” I said, “You sued my employer.”

Wilson Sayre: Technically, that was true. Dr. Bullard was a professor and researcher at Houston’s Texas Southern University, a public college.

Linda Bullard had also filed the lawsuit against the city of Houston, Harris County, Southwestern Waste Management—the company trying to build the landfill—and Browning Ferris Industries, or BFI—the company that was supposed to operate the landfill. BFI was headquartered in Houston, and for a time it was the second-largest waste-management company in the world.

Northwood Manor residents were up against an assembly of deep-pocketed defendants. Meanwhile, they collected change door to door to help pay for legal fees.

Linda Bullard told her husband they were going to need help.

Robert Bullard: She said, “I sued them, and I need someone to assist and support—gather data for this lawsuit.”

Wilson Sayre: Ms. Bullard thought the residents of Northwood Manor were on to something bigger. She thought they had a chance to prove that this dump in this black neighborhood was not an isolated incident. It was part of a pattern.

But she needed help proving that.

Robert Bullard: And I said, “You need a sociologist.” She said, “That's what you are, right?”

Wilson Sayre: Right. Dr. Bullard would take on the challenge and try to figure out if there was a pattern.

Robin Amer: That’s after the break.

ACT 2

Robin Amer: In 1979, the same year Northwood Manor residents filed a lawsuit to fight the dump proposed for their neighborhood, Dr. Robert Bullard was still a relatively new sociology professor at Houston’s historically black Texas Southern University.

Let’s go back to Wilson.

Wilson Sayre: Robert Bullard split his time between research and teaching. One of his idols was W.E.B. DuBois, who—like Dr. Bullard—was a black sociologist. DuBois was the first black person to earn a doctorate from Harvard and one of the founders of the NAACP. Dr. Bullard admired what he calls DuBois’s brand of “kick ass” sociology, combining hard research with social activism.

And now, Dr. Bullard suddenly found himself confronted with the kind of issue that DuBois himself might have tackled: Was racial discrimination to blame for Northwood Manor’s landfill problem?

Getting testimony from black residents who believed this was true wasn’t going to sway a judge. He needed to come up with solid evidence, and he needed to produce it fast enough to help stop the landfill before it could open. The clock was ticking.

Robert Bullard: When I think about that period of time, it was frantic. It was emotionally draining, because you're embarking on something, in terms of trying to collect data, you're trying to put together a puzzle that you don't have a lot of time to think about. It's full steam ahead.

Wilson Sayre: Dr. Bullard wanted to know whether there was a link between the locations of waste facilities and the demographics of the surrounding neighborhoods.

He enlisted the students from his research methods class to gather data. Their first step was to find all of the garbage facilities that had been built in Houston dating back to the 1930s.

Keep in mind, this is happening in the late 1970s. You couldn’t just Google a list of all the dumps and incinerators. Even a phone book was of little use, because going back to the 1930s meant that some of the waste facilities had been closed for years.

So, Dr. Bullard had his students digging into dusty old filing cabinets in City Hall, pulling up newspaper clippings on microfiche, and interviewing old timers in the community to ask if they remembered where various dumps had been located.

Robert Bullard: I started giving my students the list. This student may have five on a list, and they go out and verify, and we come back and put it on the map.

Wilson Sayre: And when the other methods failed, Dr. Bullard told them to trust their eyes.

Robert Bullard: I would tell my students, “If you see a mountain in Houston—Houston is flat, parts of it below sea level—if you see a mountain in Houston, be suspicious. Landfill!”

Wilson Sayre: Once his students had cobbled together the list of dumps, they looked at the demographics of the surrounding neighborhoods.

Again, this is the ‘70s. Today, a sociologist would tackle this problem with all sorts of modern tools: GPS, digital maps and powerful computer programs.

Dr. Bullard had none of these tools. They weren’t widely available at the time. When he needed to run a computer analysis, he did it using one of those massive computers you might see in a movie. It took up more space than a row of refrigerators and had significantly less computing power than an iPhone.

Robert Bullard: And I reran the data on a mainframe computer, on punch cards, so this is how ancient it is. It's like having a chisel and a hammer and a rock.

Wilson Sayre: He laid out big paper maps of Houston on the floor and used magic markers to color in neighborhoods to reflect the demographics of the people who lived there.

Robert Bullard: Yellow is less than 10 percent minority. Orange was 10 to 39. And the other one's like 40 to 49. Red was 50 percent above minority.

Wilson Sayre: Dr. Bullard used push pins to mark locations of the dumps and incinerators.

Robert Bullard: And as those pins would come in, we started seeing a pattern. Most of the pins would come in in red.

Wilson Sayre: Pin after pin went into the sections of the map colored red—the majority-black neighborhoods.

It wasn’t just the proposed Whispering Pines Landfill.

Robert Bullard: And when the pins started to come into the red, is when I knew that this was not something that was a fluke or was by accident. This was willful. It was on purpose, systematic, that city council members, over that period of time, had decided that the pins were going in the red.

Wilson Sayre: Even though he had a hunch about what they might find, Dr. Bullard was astonished at how stark the discrepancies actually were as illustrated by this map.

From the 1930s through 1978, five out of five city-owned landfills were in predominantly black neighborhoods. Six out of the eight city-owned incinerators were in predominantly black neighborhoods. And four of the four privately owned landfills were in predominantly black neighborhoods.

Robert Bullard: For me, that was an ah-ha moment. Ah-ha, oh, light bulb moment. Oh, this is an issue of discrimination. Eighty-two percent of all the garbage—the waste, solid waste—dumped in Houston over that period of time, was dumped in predominantly black neighborhoods, even though blacks only made up 25 percent of the population.

Wilson Sayre: Remember, we heard the allegation from the residents in North Lawndale and Northwood Manor that they were the ones most often stuck dealing with their city’s waste. But it wasn’t until Dr. Bullard finished his map that there was—for the first time ever—actual empirical evidence.

Robert Bullard: These are decisions made, intentional decisions, made by white men. Put the garbage over there, put it over there, put it over there. And “there,” invariably, was in black communities, black neighborhoods in Houston.

Wilson Sayre: This is what Bullard and others would ultimately call “environmental discrimination” or “environmental racism.” A practice of disproportionately burdening black and brown communities with environmental hazards that wouldn’t be allowed in white communities.

Armed with this evidence, attorney Linda Bullard felt like she had what she needed. She could argue that this type of environmental discrimination was no different than housing discrimination, or employment discrimination, or voting discrimination. It violated the Civil Rights Act.

Robert Bullard: This was the first environmental racism lawsuit to use civil rights law. And this was not something that—we didn't know what we were setting out to do, other than this was a form of discrimination. It was a form of racism in the way that environmental policies are being implemented.

Wilson Sayre: The map seemed to be the smoking gun—the type of thing that anybody with a pair of eyes could look at and realize, hey, there’s a clear connection here.

But the two judges in the case disagreed.

The judge presiding over the initial hearings was swayed by a different set of maps provided by the waste companies. Their maps purported to show that there was not a connection between landfills and black communities in Houston.

The judge found these maps more credible and sided with the landfill companies.

So how could the judge have rejected Dr. Bullard’s work?

I’m going to get a bit in the weeds with how a data analysis like this is done, but bear with me.

When Dr. Bullard did his analysis, he was looking at the demographics of the neighborhood immediately surrounding the landfill—the communities most impacted by the smell, sight, noise, and vermin of a dump.

The companies, however, used the entire Census tract where the landfill was located. That’s a much bigger area, potentially involving thousands of residents instead of just a few hundred that make up a neighborhood.

Both methods are valid, but at the time, using Census tracts was the more common and established method. There wasn’t a single, agreed-upon way to define or measure a neighborhood.

That said, it’s hard to argue that Dr. Bullard’s method was not more relevant. Think about your own home. You’re probably more likely to get upset about a dump opening at the edge of your neighborhood than one opening up at the edge of your Census tract, which could be several miles away.

So, we asked Mark Nichols, one of our data journalists at USA TODAY, to use 2018 technology to tackle the same question Dr. Bullard faced.

Here’s Mark:

Mark Nichols: What we were really trying to figure out, I think, was whether the neighborhoods in which these waste sites were contained basically had a greater proportion of non-white residents.

Wilson Sayre: I’m not going to bore you with all the details behind the analysis. But essentially, we pulled a list of all landfills operating in Houston from the state of Texas’s website. Then using a computer program called ArcGIS, Mark drew circles around the dump sites. One circle with a one-mile radius another with a three-mile radius. Then, the program pulled in all the demographic data about the people living within those circles, so we could see who was living close to these landfills.

Bottom line: Mark’s analysis squared with Dr. Bullard’s. In Houston, garbage is far more likely to wind up in the city’s black and brown neighborhoods.

But because Dr. Bullard was not able to convince the judges that his methods were sound, the residents of Northwood Manor did not get an injunction to stop the dump.

The Whispering Pines Landfill opened in 1980.

A few years later, they lost the legal battle to shut down the dump.

In a pretty scathing opinion, a second judge rejected Dr. Bullard’s map and analysis, calling it “inaccurate” and “subjective.”

By then, the landfill was estimated to be taking in between 1,500 and 2,000 tons of garbage per day.

And according to Margaret Bean, who later remarried and now goes by Margaret Lair, the landfill was as bad as the residents feared it would be.

Margaret Lair: That is when we started to see the heavy trucks speeding up and down Little York Road. At night time we smell this horrible odor.

Wilson Sayre: If you’ve ever been to Texas in the summertime, you know the heat can be intense.

Temperatures in the 90s baked the mounds of garbage piling up at Whispering Pines. Garbage would fly off the trucks and collect along the sides of the roads. Margaret Lair said that you could smell the dump’s overpowering odor throughout the neighborhood, which may be why the developer stopped building new homes there.

She told us about small white birds—what she called “dump birds”—that would land on the garbage at Whispering Pines then fly over to the high school. She worried about what germs they might be spreading to her daughter and other kids at the school.

Last year, after living in Northwood Manor for more than 45 years, Margaret Lair, moved away.

Margaret Lair: I'm happy I don't live over here anymore, but I feel for the people that still have to stay and cannot move. I was able to afford to move. You got a lot of people out here can't afford to move.

Wilson Sayre: She feels that the neighborhood started to go downhill when the landfill arrived.

She showed me and Robin around during our visit. She brought us to what used to be Smiley High School, where you could see the landfill from the bleachers at the school’s stadium.

Margaret Lair: You can actually see the dump from here. You can see, it was so close. The landfill was so close. You can actually sit in the bleachers and see the dump. The trees wasn't here.

Robin Amer: So, really close.

Margaret Lair: Very close. In fact, you could just even walk to it, it’s so close.

Robin Amer: Would you come to football games here?

Margaret Lair: Yes.

Robin Amer: And would you be able to see and smell the dump while you're sitting in the stadium?

Margaret Lair: Yes. It was a rotten odor.

Wilson Sayre: Later, Mrs. Lair drove us across the street—right up to the landfill. And it’s massive. At 180 acres, it’s nearly a quarter of the size of Central Park and ten times the size of the bigger dump in North Lawndale. And at the entrance of the facility, Robin spotted some signs. They looked like they'd been there since the dump opened in the '80s.

Robin Amer: You know, one of them says, “No dead animals, please.” And one of them says, “All tires must be split, quartered, or shredded prior to disposal. Absolutely no whole tires can be accepted.” And then there's another sign that says, “No appliances,” small appliances.

So, I mean, this to me is just an indication of, like, all of the different kinds of things that people would try to dump there, including dead animals.

Margaret Lair: Sure, they did dump their dead animals or tires or refrigerators. How would they know?

Wilson Sayre: According to state records, the dump is still taking garbage, 40 years after it first opened.

Although Northwood Manor’s residents would ultimately lose their court battle, they didn’t go down quietly. They protested at the dumps and at city hall.

Houston didn’t and still doesn’t have zoning laws, the kind of rules that prohibit industrial facilities from being built in a residential neighborhood.

But the lawsuit and the publicity from protests resulted in new laws that restricted where future dumps could go. Houston officials also decided that they would not allow any city trucks to dump at Whispering Pines.

And in what could be viewed as an acknowledgement that Dr. Bullard’s research touched on a real problem, the state of Texas changed its criteria for deciding where to place landfills. For the first time, officials had to take demographics into account before approving a new dump site.

This didn’t help neighborhoods with existing dumps, like Northwood Manor. But these changes energized Dr. Bullard.

Now, he wanted to use the same methodology he’d used in the Whispering Pines case to see if placing waste in black and brown neighborhoods wasn’t just a Northwood Manor problem, or a Houston problem, or even a Texas problem. He thought it could be something even bigger.

And he was right.

Robert Bullard: We lost the case, but we won a whole movement.

Robin Amer: That’s after the break.

ACT 3

Robin Amer: Let’s go back to Wilson.

Wilson Sayre: Robert Bullard knew that it wasn’t just piles of construction debris or landfills teeming with garbage that people didn’t want in their residential neighborhoods. Factories. Chemical plants. Contaminated land. They were all potentially harmful to people living nearby.

He wanted to understand the full extent of the problem.

Robert Bullard: I decided to go on a tear, and that was the DuBois in me, is to start writing, start documenting.

Wilson Sayre: And he started to look outside of Houston.

Robert Bullard: I want to know: is this happening in other places? So, I wrote the grant, got it funded, and I said, “I want to look at the South, see if this is a Southern thing.”

Wilson Sayre: And when he looked, he found examples of other communities that had been subject to terrible pollution. Neighborhoods near lead smelting facilities in Dallas. Hazardous waste dumps in Sumter County, Alabama. A stretch of chemical plants and refineries between New Orleans and Baton Rouge so notorious for making people sick it was known as “Cancer Alley.”

In each case, Dr. Bullard noted it was the black and brown communities most impacted.

Robert Bullard: The pattern in Houston basically was replicated across the South, and that African-American communities were being singled out for locally unwanted land uses, where landfills, incinerators, garbage dumps, chemical plants, those dangerous facilities.

It was clear that Houston was no fluke.

Wilson Sayre: Houston was not alone. Environmental hazards were disproportionately in black and brown neighborhoods, all over the country.

These were things that no one would want to live near.

Robert Bullard: Well you know, the idea that NIMBY, “not in my backyard,” had really taken hold. And instead of NIMBY, what we found was PIBBY, “place in blacks' backyard.” P-I-B-B-Y.

Wilson Sayre: Dr. Bullard wrote up his findings, first in academic journals and then in a book he titled Dumping in Dixie.

But he had trouble finding a receptive audience. He was pitching ideas that nobody had previously defined or recognized.

Robert Bullard: I got nasty notes back, saying, “Well, you can't use ‘race’ and ‘environment’ in the same sentence. You know, the environment is neutral, and so it's—there's no disparity, in terms of environment.”

Wilson Sayre: He even had trouble convincing mainstream environmental groups and Civil Rights groups that racial injustice and the environment were topics they needed to rally around together.

Robert Bullard: It took almost two decades before our civil rights organizations and our green groups understood how these two things connected.

Wilson Sayre: But through his research, Dr. Bullard started hearing about other black and brown communities all over the country that were also banding together to fight toxic dumps, landfills, and other industrial facilities in their neighborhoods.

A group in rural North Carolina had fought the dumping of toxic oil along the roads in their community. A group in Dixon County, Tennessee, was trying to fight a landfill. Researchers were looking at the locations of hazardous waste facilities in Los Angeles. And there were more.

These were relatively small, grassroots groups. But a name for what they were seeing started to take hold. It pointed to a broader understanding that this growing national movement was about more than just stopping individual landfills from popping up in certain areas.

This was environmental racism. And the people involved in the movement against it were fighting for environmental justice.

This group of people from all over the country fighting for environmental justice started to meet and hold conferences throughout the early 1990s.

They were trying to change the system that had allowed a mountain of construction debris to pile up in Chicago’s North Lawndale neighborhood with no repercussions—a situation that was unfolding around this very same time.

It had taken the Voting Rights Act to address voting discrimination, and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act to address workplace discrimination. So, this group of environmental justice advocates began to push for the same kinds of landmark legal protections to reckon with environmental discrimination.

They started writing letters to government officials.

Robert Bullard: We wrote letters to the EPA, we wrote letters to the President's Council on Environment Quality, we wrote letters to Health and Human Services, and we were requesting a meeting, a sit-down meeting.

Wilson Sayre: And they got one!

In 1991, they met with the head of President George H.W. Bush’s EPA.

Out of that meeting, the EPA created the Office of Environmental Equity—a division of the federal government tasked with studying the problem of environmental discrimination.

A year later, the EPA released a report called “Environmental Equity: Reducing Risk for All Communities.” It echoed what Bullard and his colleagues in the movement and some communities had been saying all along: black and brown neighborhoods were disproportionately burdened with environmental hazards.

But the big moment for this movement came in February 1994.

Dr. Bullard and his colleagues were at a conference just outside of Washington, D.C.

Robert Bullard: A few of us got a call from the White House to come over to witness something.

Wilson Sayre: They’d been invited into the Oval Office to witness President Bill Clinton sign a new executive order.

Robert Bullard: We went in and Vice President Al Gore was the first to greet us when we came through the door. And then President Clinton was in the background just in front of his desk.

Wilson Sayre: The Environmental Justice Executive Order of 1994 instructed every federal agency to ensure that no one group of people was unfairly burdened with the country’s waste.

While the president signed the executive order, Dr. Bullard and the other activists gathered behind the president's desk for a commemorative photo.

We showed the photo to Dr. Bullard.

Robert Bullard: Yeah, yeah. Yeah, that's Dr. Wright, Beverly Wright, there. And that's Sen. Wellstone. I was standing next to EPA Administrator Carol Browner. And John Lewis was there, and Sen. Carol Moseley Braun, the senator from Illinois. And the Attorney General, Janet Reno was there. John Lewis. And we were all smiling.

Wilson Sayre: These activists, the parents of the environmental justice movement, were here to watch their movement legitimized by the highest official in the country.

The measure acknowledged that environmental racism was real. It was also a pledge that the federal government would do something about it.

Robert Bullard: We were all just really—we never thought that this is something that would happen. Environmental justice had reached the White House.

Wilson Sayre: Later the same day, Carol Browner, then head of the EPA, walked into the White House press room, and declared that it was time for the federal government to ensure environmental justice for every community in America.

Carol Browner: The president, joined by representatives from community groups across this country, just signed an executive order. Nobody can question that for far too long, communities across this country—low-income, minority communities—have been asked to bear a disproportionate share of our modern industrial life. Today's executive order is designed and will seek to bring justice to these communities.

Wilson Sayre: Standing next to Browner during the speech was US Attorney Janet Reno. She committed her agency’s prosecutors to holding people and companies accountable for environmental discrimination.

But at the very moment that President Clinton was signing the environmental justice executive order at the White House, in Chicago, Operation Silver Shovel was underway. A mob-associate-turned-undercover-informant by the name of John Christopher was illegally dumping debris in Chicago’s black neighborhoods—and he was doing it while working for the FBI.

If you tried to draw a big enough org chart of the Justice Department at the time, John Christopher’s boss’s boss’s boss’s boss or whatever, you get it, was US Attorney Janet Reno.

Recognizing a problem and doing something about it are two very different things.

After the signing ceremony in Washington, it would still be another two years before Operation Silver Shovel thrust John Christopher’s illegal dumps into the limelight. And even then, it wasn’t angry residents writing letters, or kids getting sick or injured, that shamed government officials into fixing the problem.

It wasn’t even a newfound commitment to environmental justice.

What ultimately got all that debris out of North Lawndale was the publicity that followed a major public corruption scandal featuring a mob-connected mole.

The kind of publicity that other communities across the United States will never get.

Robin Amer: The outrage and embarrassment that followed in Silver Shovel’s wake sparked a glimmer of hope, as political leaders rushed in to try and fix the problem in North Lawndale.

Gladys Woodson: The Silver Shovel story broke, and then, the next thing I saw was Jesse Jackson standing on top on the pile saying, “Oh, yeah, we did this.” And we was saying, “No you didn’t.”

Robin Amer: That’s next time on The City.

CREDITS

The City is a production of USA TODAY and is distributed in partnership with Wondery.

You can subscribe to the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you’re listening right now. If you like the show, please rate and review us, and be sure to tell your friends about us.

Our show this week was reported and produced by Wilson Sayre, Jenny Casas, Sam Greenspan, and me, Robin Amer. Additional reporting for this episode by Mark Nichols.

This episode was edited by Matt Doig with additional editing from John Kelly and Amy Pyle.

Ben Austen is our story consultant. Original music and mixing is by Hannis Brown. Legal review by Tom Curley.

Additional production by Taylor Maycan, Fil Corbitt, Isobel Cockerell, and Bianca Medious.

Our executive producer is Liz Nelson.

Chris Davis is our VP for investigations. Scott Stein is our VP of product. The USA TODAY NETWORK’s president and publisher is Maribel Wadsworth.

Thank you to our sponsors for supporting the show. And special thanks to Scout Blum, Misha Euceph, and Danielle Svetcov.

Additional support comes from the Fund for Investigative Journalism and the Social Justice News Nexus at Northwestern University.

You can find us on Facebook and Twitter @thecitypod. Or visit our website, where you can see the Oval Office photo of Bill Clinton and Robert Bullard and the other environmental justice activists.

Then, if you’re in Chicago, please join me and the rest of The City team on Wednesday December 5th for a live community conversation, co-sponsored by WBEZ. We’ll be at the Skyline Conference Center in North Lawndale. We’ll take you behind the scenes of the podcast and introduce you to some of the North Lawndale residents of who fought to get rid of the Mountain.

To reserve tickets, visit thecitypodcast.com

PEOPLE

(Photo: Robert Bullard)

PLACES

WATCH

EPA Administrator Carol Browner and US General Attorney Janet Reno commit their agencies and the rest of the federal government to the work of environmental justice. This announcement came shortly after the signing of the Environmental Justice Executive Order. At this very same time, Operation Silver Shovel was underway under the direction of Reno’s Department of Justice. The illegal dumps in North Lawndale would stand in North Lawndale for two years after this commitment to environmental justice.