S1: Episode 5

The ‘Forrest Gump’ of Chicago Crime

A bank failure unearths a connection to the mysterious man in the limo—and suddenly, he’s everywhere. Bribery, fraud and violence are just ways of doing business. The FBI is on the case—but which one? And whose?

Episode | Transcript

The ‘Forrest Gump’ of Chicago Crime

Robin Amer: Henry Henderson was at his wit’s end.

Henry Henderson: The city was like a vacuum sucking in illegal dumping activities. This is clearly wrong. This is clearly illegal and there clearly is the authority to make this stop.

Robin Amer: The commissioner of Chicago’s Department of the Environment had spent the last several years fighting John Christopher’s illegal dumps. And yet, the mountains of debris remained in North Lawndale.

Henderson had reasoned with John Christopher. He had threatened him with legal action and had eventually taken him to court. But even with a civil ruling against him, the courts had failed.

Henderson had even turned to the state Environmental Protection Agency. None of it had worked.

Henry Henderson: Well, John Christopher basically disappeared.

Robin Amer: Henry Henderson had not been able to bring John Christopher to justice—or get justice for the people of North Lawndale. But he had one more card to play.

Henry Henderson: Scott's an old friend and he was first assistant at the time.

Robin Amer: Henderson called on Scott Lassar—First Assistant US Attorney in the Northern District of Illinois. In other words, one of Chicago’s top federal prosecutors. Lassar’s office had the power bring federal criminal charges against John Christopher.

Henry Henderson: And saying, you know, we're having a real hard time. And we think that this is a larger criminal criminal endeavor here. And we really need some help.

Scott Lassar: Henry was like Inspector Javert going after Christopher.

Robin Amer: That’s Scott Lassar. And Inspector Javert is the police inspector from Les Misérables, who relentlessly hunts down the main character over the course of the story. It’s not a perfect comparison, but basically, Lassar knew Henderson was on a mission.

Scott Lassar: He knew about Christopher and he'd been pursuing him for a long time.

Robin Amer: And even though they were friends, Lassar gives Henderson the brush off.

Scott Lassar: I had to rebuff him.

Robin Amer: Lassar basically says, "Sorry, Henry, we can’t help you catch this John Christopher guy. The DOJ doesn’t work on municipal waste issues."

But that wasn’t the real reason.

Scott Lassar: We couldn't tell Henry Christopher was working undercover at that time.

Robin Amer: Not only did the federal government already know all about John Christopher, John Christopher was on its payroll. Even while he was dumping in North Lawndale.

Scott Lassar: This was a secret undercover investigation. It was one of the more successful undercover investigations that our office conducted and so we weren't going to end it.

Robin Amer: Chicago’s most notorious illegal dumper was also working for the FBI.

I’m Robin Amer, and from USA TODAY, this is The City.

ACT 1

Robin Amer: So who was this guy who showed up to a vacant lot on Chicago’s West Side in a limousine? Who was John Christopher really?

To answer that question, we need to go back to January 1979 and then-mayor Michael Bilandic.

Michael Bilandic: We had 24 million tons of snow—over 24 million that fell. The city of Chicago has been labeled an emergency area by the federal government.

Robin Amer: Even in the pantheon of Chicago winters, this was one for the ages. People still talk about the Blizzard of 1979. And not just because of all the snow. Bilandic had to defend his administration’s response to this record snowfall to an angry and skeptical City Council.

Michael Bilandic: We have enough snow here and enough streets, 4,000 miles of streets. That's the distance from Chicago to Los Angeles and back.

Robin Amer: Meteorologists had forecast just two to four inches of snow. And so Chicago was completely unprepared when the blizzard instead dumped more than 20 inches on the city. The storm collapsed roofs and trapped people in their homes paralyzing the city for weeks. And getting rid of all that snow would prove to be a monumental challenge for the city.

Michael Bilandic: When you're concerned about getting equipment and people out to the street, you're not doing an accounting at the same time. We'll have an opportunity to do that at a later point.

Robin Amer: The ensuing cleanup—and that lack of accounting—presented a perfect opportunity for then-28-year-old John Christopher. The city hired private contractors to help clear the streets. And Christopher had a guy inside city government who paid him for snow removal work he never did.

Jim Davis: I think that it is fair. I don’t recall the exact facts of that case, but I can say that he was alleged to have been submitting false invoices and getting paid for that by the city.

Robin Amer: This is Jim Davis. He was an FBI agent from 1985 to 2011. And this epic snowstorm would eventually cause his life to intersect with John Christopher’s in a very big way.

Jim Davis: I talked to John every day, multiple times every single day from July of 1992 until January of 1996. You know, I probably had a closer relationship with him during that time than anyone else, and it was a kind of a love/hate relationship.

Robin Amer: If you Google “Jim Davis FBI,” one of the first hits you get is a photo of very tall man in a black shirt, with dog tags around his neck. That’s Jim Davis. He’s standing in front of a white tiled wall and he’s looking straight at the camera.

In one hand, he’s holding a piece of paper that reads: “FBI—12 December 2003.”

And his other hand is resting on the shoulder of Saddam Hussein.

Jim Davis: I arrested Saddam Hussein, you know. I'm telling you, man, life is like a box of chocolates, man. I am the Forrest Gump of the FBI.

Robin Amer: Jim Davis calls himself the “Forest Gump of the FBI” because he has a tendency to show up in big moments in history—like Saddam Hussein’s arrest. He and John Christopher were well matched in that way—a federal prosecutor gave John Christopher almost the same nickname: Chicago’s “Forrest Gump of crime.”

Robin Amer: In the many hours they later spent together, Jim Davis learned a lot about John Christopher’s illegal schemes—including the one he pulled during the Blizzard of ‘79.

Jim Davis: He had gone to some corrupt folks at the driver's license bureau, the Secretary of State's office, that he had had a previous relationship with. He got a driver's license in the name of a Richard McCann.

Robin Amer: In the chaos after the blizzard, John Christopher was part of a group of people that conspired to defraud the city. They submitted fake invoices for snow removal work they never did. The company name they used was “McCann Construction,” so the city issued a check in the name of Richard McCann—the name on John Christopher’s fake ID.

The check was for $112,000—a decent haul for not clearing so much as a teaspoon of snow.

So, check in hand, John Christopher walked into a bank.

He tried to cash the check. But something about him raised a red flag with bank employees, who asked him for his ID.

Jim Davis: John provided a driver's license, and these guys looked at John, who is Italian, and said, "You don't look Irish."

Robin Amer: John Christopher responded by saying he was adopted. But McCann—the name on his fake ID—had blown his cover.

And so John Christopher handled these bank employees the way he normally handled people who got in his way. He tried to bribe them.

He offered to take the vice president of the bank out to lunch, and when that didn’t work, he offered him a Betamax—an expensive precursor to the VHS. But the bank manager didn’t budge.

Jim Davis: So he ended up calling the FBI.

Robin Amer: The city had paid John Christopher from a pool of money that came from federal disaster relief funds. Which meant that John Christopher hadn’t just defrauded the city. He had also defrauded the federal government.

The FBI arrested John Christopher, and he now faced up to 15 years in prison.

Without knowing it, he’d also helped alter the course of Chicago history.

More than 30 other companies were also investigated for defrauding Chicago’s snow disaster fund. At least one city official was indicted for helping them.

And Mayor Bilandic was blamed for letting it all happen on his watch.

In the next election, he’d lose to an upstart, anti-Machine candidate named Jane Byrne, who became the only woman ever to serve as Chicago’s mayor. This is why people still talk about the Blizzard of 1979. It wasn’t just all the snow. It was the political fallout.

Robin Amer: Maybe you can start to see where John Christopher got his nickname—the “Forest Gump” of Chicago crime. But his criminal activities started long before than this.

John Christopher grew up just a few miles from North Lawndale, in an Italian neighborhood full of families descended from the old Taylor Street crew—one of the original street crews of the Chicago Outfit. Which in Chicago, is what we call the mob.

Jim Davis: His great-uncle was a guy named Fiore Buccieri. They called him Fifi, and he was kind of a notorious mob guy in the ‘50s and ‘60s.

Robin Amer: The press described Buccieri as a “West Side overlord” in charge of loan sharking and other rackets. He was also suspected of having been involved in multiple murders, one of which was incredibly gruesome.

I will spare you the details, but I can tell you that it involved a blow torch and a cattle prod. Buccieri was later caught on an FBI wire laughing and bragging about it.

He was never indicted for murder, but he was indicted late in life for, theft, soliciting others to commit theft and possession of $200,000 worth of stolen construction equipment.

John Christopher’s crimes, at least the ones he told the FBI about, started when he was a teenager.

Jim Davis: He was a tough street kid and, if you look at some of the transcripts, he often refers to himself as being on the corner or, "This is the way I operate on the corner. Some guys go to college, I came from the corner."

Robin Amer: When he was a teenager in the mid-to-late ’60s, John Christopher joined a neighborhood street gang called the Jokers. He’d later tell Jim Davis that the Jokers would “protect” their neighborhood from any “undesirable elements.”

That meant mostly black families who were moving to the West Side as it transitioned from white to black. John Christopher and the Jokers threatened and intimidated these newcomers and, in some cases, threw Molotov cocktails into their buildings.

Robin Amer: John Christopher was arrested at 19 for breaking into cars. He tried to bribe both the arresting officer and the judge. He was sent to the army instead of prison, but was honorably discharged soon after. He told the FBI he thought his Great Uncle Fifi had something to do with getting him out.

A few years later, his father got him a job with the Department of Streets and Sanitation. John Christopher and the other workers would often sit around the office, playing cards instead of working.

One day, someone from the inspector general’s office caught them slacking off. The inspector threatened to report them, so John Christopher and his colleagues beat up the inspector and told him to write a good report on the unit—which he did.

But ultimately, defrauding the federal government after the Blizzard of 1979 was what put him on the FBI’s radar.

John Christopher’s snow-fraud case went to trial in 1980, but ended in a mistrial. And while he was waiting for a new trial to begin…

Jim Davis: He was looking for a silencer to kill a witness against him.

Robin Amer: A silencer. Silencers are those devices you attach to the muzzle of a gun to muffle the sound of a shot. They were—and still are—illegal in Illinois.

The FBI had gotten word from an informant that John Christopher was in the market for a silencer, allegedly so he could murder a federal witness. So the FBI coordinated with an undercover agent from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms in order to sell him one.

Jim Davis: I mean it was a buy-bust scenario, right? It all just happened at once.

Robin Amer: John Christopher was sentenced to four years in federal prison for possession of the silencer and another eight years for trying to cash the snow removal check.

But behind bars, he stayed true to his roots.

Jim Davis: John, he didn't rat.

Robin Amer: In the parlance of the Outfit, John was a “stand-up guy.” He didn’t snitch on anyone else who’d been involved in the snow fraud, even though he could have parlayed that information for a lighter sentence.

Jim Davis: You know, John's a—he's associated to the mafia in Chicago, and there were other people that were involved in that scheme that John didn’t give up. So, he went to prison for them, didn't take anybody down. And in return…

Robin Amer: In return, Jim Davis says John Christopher expected the mob to support his family since he would not be able to provide for them while he was locked up.

Jim Davis: And I think that he expected that. For that, they would do a better job at taking care of his family while he was in prison, and they hadn't done that.

Robin Amer: After roughly four years in federal prison, John Christopher was put on parole.

He returned to his old ways, but he also came back with doubts about his loyalty to the mob.

This is ultimately how Jim Davis would become John Christopher’s FBI handler. When the bureau exploited John Christopher’s doubts about the mob and he crossed over and started wearing a wire.

That’s after the break.

ACT 2

Robin Amer: When John Christopher got out of prison in the late 1980s, he came back to Chicago, and started a construction company. One that did road repair and paved parking lots and crushed gravel. By June of 1990, he had set up his illegal dumps in North Lawndale.

And to help establish his new business, he turned to a familiar ruse: bank fraud.

John Christopher’s second run-in with the FBI starts with a bank failure.

Jim Davis: John had made some false statements related to loans that he had received from Cosmopolitan Bank to buy his trucks for his business.

Cosmopolitan National Bank goes belly up—it fails. And that attracts the attention of the FBI’s financial crimes squad.

Jim Davis: An agent there named Tony D'Angelo, he identified John Christopher as a subject in that investigation.

Tony D’Angelo: Basically what I did was I looked at everything that was going on in the bank.

Robin Amer: This is Tony D’Angelo. Cosmopolitan Bank had seemed like it was thriving—with money in its vault and plenty of account holders.

Tony D’Angelo: And I'm wondering, how can a well-capitalized bank in the late 1980s all of a sudden going to receivership? That's highly unusual. So I looked at the bad loans.

And who turns out to be at the center of this bank failure?

Tony D’Angelo: Once I looked at the bad loans, probably the biggest bad loan at the bank was for an individual named John Christopher and his various entities.

Tony D’Angelo: Mr. Christopher had a couple of trucking companies, some other businesses, and he had borrowed, I can't remember the exact amount, but I believe the total deficit to the bank was in the millions.

Robin Amer: $2.5 million. That’s what John Christopher would later say in court.

Tony D’Angelo: And he also overstated the success of his companies, his trucking businesses. So he basically made up income that was not there.

Robin Amer: It looked like John Christopher had used these bad loans to build up his business.

Tony D’Angelo: And it's easy to build up your business, especially when you're not paying loans back.

Robin Amer: So Tony D’Angelo does a background check on John Christopher and finds he’s already in the FBI’s database.

Tony D’Angelo: I was amazed because found out he was a convicted felon, organized crime.

Robin Amer: Tony D’Angelo learns all about the snow fraud case and the silencer and the alleged plan to murder a federal witness. And about John Christopher’s ties to the Outfit.

Tony D’Angelo: I knew he was extremely bad news.

Robin Amer: With this criminal background, it was highly unlikely that John Christopher would actually qualify for millions of dollars in bank loans. So Tony D’Angelo begins to suspect that the bank president must be in on it.

D’Angelo wanted to use John Christopher to get to the bank president, but…

Tony D’Angelo: Everybody told me John Christopher will not talk to you. There's absolutely no reason to cooperate. He's not going to talk to you. It's a waste of time.

Robin Amer: He decides to try anyway. He finds John Christopher’s number and calls him.

Tony D’Angelo: And he actually picked up the phone. I introduce myself. I take a low key approach. So I told him who I was—“I looked at your your dealings with Cosmopolitan Bank and I've got you on financial fraud with your loan application.”

Robin Amer: You might think John Christopher would just hang up the phone at this point. But Tony D’Angelo says, "Just meet with me. All you have to do is listen."

Tony D’Angelo: And I found in my career that people are very curious. They want to know what information you have about them, what evidence. I also mentioned to him, “You know, I know you just got outta jail. You got a couple kids. Maybe we can help each other.”

So ultimately, he agreed to meet me. He wanted to meet me alone. I did meet him alone. We met at a Pizza Hut in Cicero, Ill.

Robin Amer: Cicero is a suburb just west of Chicago. It’s where Al Capone based a lot of his operations. And this Pizza Hut was less than a 10-minute drive from the North Lawndale dumps.

So when Henry Henderson, the environment commissioner, says...

Henry Henderson: Well, John Christopher basically disappeared.

John Christopher was just a mile or two away—eating pizza with the FBI.

Here’s how Tony D’Angelo describes that first meeting.

Tony D’Angelo: John Christopher was out of a central casting for The Sopranos. I mean if you want to know a mobbed-up guy, take a picture of John Christopher. Built like a bull. About 5'10”. Stocky. No neck. Wearing a Members Only jacket. Talking in “dems” and “dose,” and, uh, just—just a funny guy.

So, I laid out my case against him. “You know,” I said, “I'm a fellow Italian. Why don’t we meet a couple more times? You can just listen to me talk. You don't have to do anything.” So we established a comfort level.

Robin Amer: So they meet again, at the same Pizza Hut in Cicero.

Tony D’Angelo: I knew he had, I think it one of his sons was about eight or 10, and the during the first conversation, he mentioned that his son liked baseball. I brought him a box of baseball cards for son.

Robin Amer: They talk again. And again. And again. And pretty soon, they’re talking regularly.

But they’re not talking about the dumps, or the people living near them.

Tony D’Angelo: Uh, so with each meeting you uh, you establish more of a rapport, more of a trust factor get to know each other and um, I'm doing analysis of him what's making him tic.

Robin Amer: Tony D’Angelo learns that John Christopher is still angry about the way his family was treated while he was in prison.

Tony D’Angelo: That promises were made and they were broken. Usually, he wouldn't bring something like that up. So that was something that, you could tell he was harboring a deep-seated uneasiness or resentment over over his family not being taken care of. I think he was really scared about serving another long stretch in prison and not seeing his kids, knowing that they're going to be teenagers and not being there to have any influence over their lives.

Robin Amer: Slowly but surely, John Christopher starts to give the FBI information. First, about Cosmopolitan National Bank—the bank president would later be convicted for bribery, bank fraud, and tax evasion.

And pretty soon, John Christopher would give the bureau much much more.

That’s after the break.

ACT 3

Robin Amer: FBI Special Agent Tony D’Angelo had made himself a fixture in John Christopher’s life.

Tony D’Angelo: I would travel around with him and go to meetings with him and I had a cover. John introduced me as his pinheaded lawyer from down in Springfield.

Robin Amer: Wait, what kind of meetings would you go to with him?

Tony D’Angelo: We had a meeting at once in Greektown, and the owner of the restaurant came up, and John, you know, he'd get a cup of coffee, and rather than use a spoon, he’d stick his big fat finger in there and stir it up. And he looked at the owner of the restaurant, he goes, “If you don't pay your milk money, you're going to get a pineapple through the window.”

Robin Amer: In other words, he’s threatening to bomb the restaurant.

Tony D’Angelo: And I guess this guy may be had fallen behind on his payments. That's probably why John picked this restaurant for the meeting.

Robin Amer: The FBI was grooming John Christopher as an informant—and here he was making threats right in front of one of its agents.

Tony D’Angelo: I kicked him under the table and he looked over and forgot I was sitting there.

Robin Amer: In moments like these, John Christopher was inadvertently revealing that his crimes still went way beyond bank fraud. Crimes the FBI was willing to overlook, like that six-story dump in a certain West Side neighborhood.

Tony D’Angelo: One day during one of these meetings he goes, “Oh, are you interested in politicians?”

Robin Amer: John Christopher saying this to an FBI agent—this was a big deal. Remember, John Christopher was a “stand-up guy.” He never ratted on anyone, even when it could have meant less prison time.

And he knew the stories about his Great Uncle Fifi, about what the mob could do to anyone who crossed them.

But John Christopher had done the math. Given all the evidence Tony D’Angelo had amassed against him, he was almost certainly facing prison time for the Cosmopolitan Bank fraud. And based on what had happened before, he suspected that if he went back to prison, his family would not be taken care of.

So when John Christopher asks, “Are you interested in politicians?”

Tony D’Angelo: I said, absolutely. What do you have on politicians? Well, little did I know at the time that John Christopher have been bribing and paying off and doing whatever he needed to do with aldermen and various city officials.

Robin Amer: Tony D’Angelo had just landed a major informant. One so big he was now outside of his purview.

So the FBI calls on its public corruption squad and Special Agent Jim Davis.

And at first, Jim Davis is skeptical about this new informant.

Jim Davis: Hey, I'm an FBI agent. I'm skeptical of everybody. It just kind of sounded too good to be true from the perspective of a guy doing a corruption investigation. You know, this guy walks in the door and basically says, “I'm a bribing machine,” and I was trying to verify that. I wanted to make sure that he was telling me the truth.

Robin Amer: As they’re sitting down for one of their first interviews, Jim Davis decides to give John Christopher a little test—to see if he’s really equipped to bribe an elected official.

Across the interview table, Jim Davis asks John Christopher how much money he has on him. And in response, John Christopher stands up and empties his pockets, pulling out change and balls of lint and gum wrappers.

Jim Davis: So I said, “OK, John, if a public official came by today and said, ‘I need $500,’ what would you do?”

And he says, “Oh,” and he reached into his back pocket, and he pulled out five $100 bills that he kept in his back pocket specifically for paying bribes, and that's the way he walked around life.

Robin Amer: John Christopher tells Jim Davis that he’s been bribing 24th Ward Alderman Bill Henry to the tune of $5,000 a month. And not only Bill Henry.

Jim Davis: John said to us that he'd been paying public officials his entire life.

Robin Amer: There’s another alderman whose palm he greased in exchange for help setting up yet another rock crusher. There are city inspectors who showed up at the dumps. There are city workers. He’d bribe them even if he wasn’t totally sure what they could do to help him just as a way of “keeping [the] heat off.”

Jim Davis: He had grown up in Chicago, doing business in Chicago, committing kind of petty crimes when he was a younger kid that they resolved by bribing police officers or prosecutors.

Robin Amer: To John Christopher, this was just the cost of doing business.

Jim Davis: So his entire life had been kind of ingrained with this idea that you paid public officials to get through life.

Robin Amer: To people in North Lawndale, the illegal dumping was the only one of John Christopher’s crimes that mattered. But the FBI’s interest was elsewhere. To the bureau, the illegal dumps were just one chapter in John Christopher’s long criminal history.

Why take him down for dumping on the West Side when you could instead use him to catch corrupt city officials all over town?

Because if John Christopher really was this “bribing machine,” then he presented the FBI with a unique opportunity. If he could wear a wire—and record his meetings with city officials—record his bribes to city officials—there was no telling how many crooked politicians they could catch.

Because here’s this guy—a stand-up guy who never ratted—who’s engaged in all kinds of illegal activity. Who’s connected to the Outfit. He’s the great nephew of notorious Chicago mobster Fifi Buccieri! He’s the “Forest Gump” of Chicago crime!

He’s exactly the kind of guy who you’d never suspect of working for the FBI, which would make him the perfect FBI mole.

Jim Davis: I don't think that we've ever had anybody who had his level of credibility who was working with us. I had a sense that this was going to be a big case.

Robin Amer: And so, when Henry Henderson reaches out to his friend, Scott Lassar, the federal prosecutor, saying…

Henry Henderson: This John Christopher is much larger than what we can do. And we think that this is a larger criminal criminal endeavor here. And we really need some help.

Robin Amer: Scott Lassar had to give Henderson the brush off...

Scott Lassar: I had to rebuff him.

Robin Amer: ...because John Christopher had already been recruited by the FBI.

Scott Lassar: We couldn't tell Henry about it. Christopher was working undercover at that time.

Robin Amer: The feds could have sent John Christopher to prison in 1991. Federal prosecutors could have gone after him for illegal dumping. The mountain, the dust and the asthma, the cracked foundations—the feds could have ended it all. But letting it continue was useful.

Scott Lassar: This was a secret undercover investigation. It was one of the more successful undercover investigations that our office conducted and so we weren't going to end it. I mean, we knew about the illegal dumping going on very well, because that was at the heart of the the investigation.

That’s next time on The City.

CREDITS

The City is a production of USA TODAY and is distributed in partnership with Wondery.

You can subscribe to the show on Apple Podcasts, NPR One, or wherever you’re listening right now. If you like the show, please rate and review us, and be sure to tell your friends about us.

Our show was reported and produced by Wilson Sayre, Jenny Casas, and me, Robin Amer.

Our editor is Sam Greenspan. Ben Austen is our story consultant. Original music and mixing is by Hannis Brown.

Additional production by Taylor Maycan, Isobel Cockerell, and Bianca Medious.

Chris Davis is our VP for investigations. Scott Stein is our VP of product. Our executive producer is Liz Nelson. The USA TODAY NETWORK’s president and publisher is Maribel Wadsworth.

Thank you to our sponsors for supporting the show. And special thanks to Misha Euceph and Danielle Svetcov.

Additional support comes from the Fund for Investigative Journalism and the Social Justice News Nexus at Northwestern University.

If you like this show, you may like WBEZ’s new podcast, On Background, which takes you inside the smoke-filled back rooms of Chicago and Illinois government to better understand the people, places, and forces shaping today’s politics.

I’m Robin Amer. You can find us on Facebook and Twitter @thecitypod. Or visit our website, where you can find photos of the Blizzard of 1979 and more.

That’s thecitypodcast.com

READ MORE

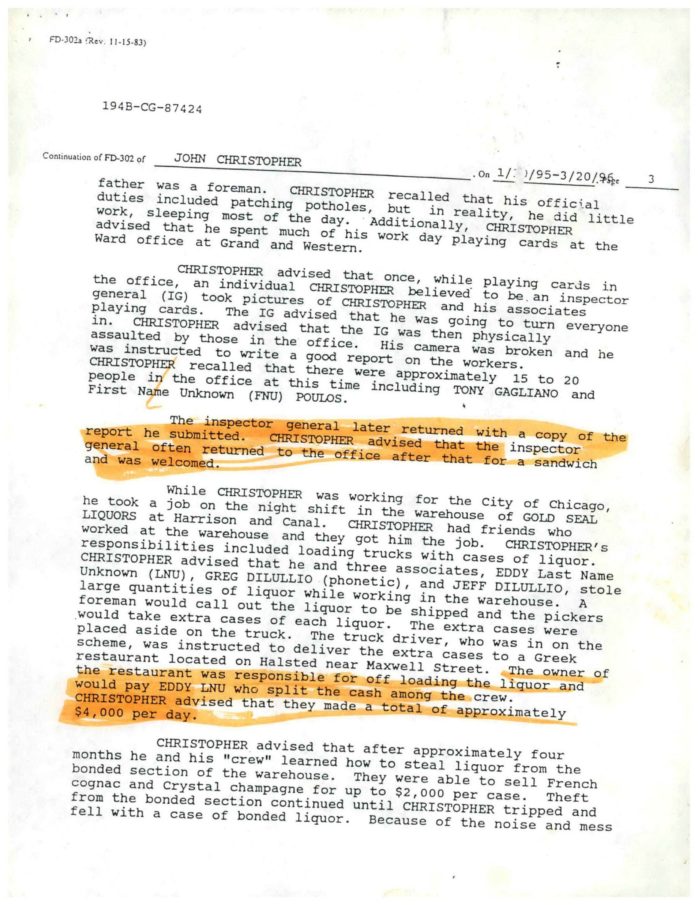

This document is a page from a partial FD-302 report, which details what John Christopher told the FBI under questioning—including the various crimes he committed before he started dumping in North Lawndale in 1990.

PLACES

His target: The Cosmopolitan National Bank of Chicago. (Photo: Chicago Sun-Times)