S1: Episode 4

A Tale of Two Cities

Four years in, “Mount Henry” has become a magnet for hazardous waste—both literal and figurative. A new illegal dump appears in a white neighborhood. A trusted advocate may not be who he seems.

Episode | Transcript

A Tale of Two Cities

Robin Amer: When Deyki Nichols was a kid growing up in North Lawndale in the early 1990s, he knew that lurking near his home...was an evil rabbit.

Deyki Nichols: It was (laughs) a myth that there was an evil rabbit up there. It was a grown rabbit. It used to chase kids, with red eyes. (laughs) I still remember that. It used to chase—we went looking for it one day, but never seen that evil rabbit. (laughs)

Robin Amer: This evil rabbit roamed the neighborhood’s hills and mountains—the ones made from construction debris. Older boys told this story to younger kids like Deyki to keep them away. It didn’t work.

Deyki Nichols: We played up there, everything—play hide and go seek. That was our go-to. That’s what we did. We played up there, everything. Lot of fun times. Lot of fun times. I mean, when it snowed, we’d get sleds and slide down there, and when it was summertime, you’d ride your bike up and down the hills, because it was that big a hill. That was fun.

Robin Amer: From up on the hills, Deyki and his friends could look down onto the roof of their elementary school, and see all the basketballs and footballs that neighborhood kids had gotten stuck up there over the years. And they could look east, towards the horizon, and see all the skyscrapers downtown.

Grass and plants and trees sprouted from the concrete hills. Old mattresses became trampolines. Junked out cars became jungle gyms.

Deyki Nichols: That's what we needed. That's what the neighborhood needed as a kid. Because it wasn't no park. I mean it wasn't no park in that area. But as an adult, it's an eyesore. It was. It brought the community down.

Robin Amer: These hills—this mountain—were John Christopher’s illegal landfill, of course. By now, six stories tall, two whole city blocks wide, and five city blocks long. The piles had been that way for two years—which, to a kid, was basically forever. At this point, the hills were just part of the neighborhood’s geography.

There was a doughnut factory on one side of the dump, where Deyki and his friends would dumpster dive for discarded treats. Instead of using the streets to get there, cutting through the hills was often safer or just more fun.

Deyki Nichols: We didn't know better. We just knew you gotta go through the forest to get to the the donut factory. Man, I remember a time we didn't even have food in the house, and that that probably got us through the week. Was the eating donuts and cakes and cookies.

Robin Amer: Spend enough time on a six-story mountain of rubble, and someone is bound to get hurt. Deyki remembers this one time, around fourth grade, when he and his brother were playing there. Deyki was rolling rocks and chunks of concrete down the side of the mountain. And one of them rolled towards his brother.

Deyki Nichols: I mean, it rolled over his finger, and it was hanging off. So I had to hold it together and I had to walk him all the way home holding his finger on until we got to the hospital. They had to reattach it. They had to—he had to spend about two or three days in the hospital because it was, it was off.

Robin Amer: At the beginning of our story, when the trucks full of construction debris first appeared in North Lawndale, Delores Robinson was a math teacher at Sumner Elementary School. Eventually, she became the principal—but she still struggled to keep her students out of the dumps.

Delores Robinson: Deyki was one of them. I'm like, "Stop it. I don't want you doing that.” I said, "I'm looking out the window at you." And so I know the boys who were, you know, playful and athletic.

Robin Amer: So Ms. Robinson installed a regular teachers’ patrol to keep eyes on the kids coming and going from school. It wasn’t just accidents like the kind Deyki Nichols’s brother had suffered that worried her—or evil rabbits.

Delores Robinson: It was reported a dead body was found.

Robin Amer: Ms. Robinson didn’t know whether it was true or not. But she repeated it to her students. Like the story of the evil rabbit, it was a way of scaring them away from the dumps.

As it turned out, she wasn’t the only Chicago educator trying to shield her students from a dump like this. Because across town, in a white neighborhood—where residents had the ear of the city’s powerbrokers—a new dump next to another school was also on the rise.

The steps that parents and kids would take to protect these two neighborhoods—one white and one black—got very different responses from the people in power.

I’m Robin Amer, and from USA TODAY, this is The City.

ACT 1

Robin Amer: Before we tell you about the dump in the white neighborhood across town, let’s recap what’s happened in North Lawndale since our story began.

After John Christopher showed up and started dumping, neighborhood residents organized.

They wrote letters to elected officials. They confronted John Christopher. They helped initiate a lawsuit against him and his companies.

But the lawsuit didn’t stop him from dumping and the mountain of rubble continued to grow—as did the threat it posed to the people of North Lawndale.

However, there was still a chance that the court could rule in the neighborhood’s favor.

Our reporter Wilson Sayre picks up the story from here.

Wilson Sayre: North Lawndale residents had now been fighting the illegal dumps for two years. Frustrated by how long the problem had dragged on, they started looking for new ways to fight John Christopher.

Michelle Ashford: A group of people, we started protesting. We would stand out there with signs.

Wilson Sayre: That’s Michelle Ashford. Remember, she was a teenager back then—when the dust from the dump would get caught in her lip gloss.

Michelle Ashford: And it was getting worse instead of getting better. We were just constantly protesting about this dump, and it was getting worse instead of getting better.

Wilson Sayre: The Ashfords protested as a family. Michelle’s mom, Rita Ashford, was on the front lines, because, if you recall, three of her grandkids, and many of her neighbors’ kids, were in and out of the hospital with severe asthma.

Rita Ashford: So the first time we went down there, you know, we just marched with signs and different stuff like that.

Wilson Sayre: They made signs that called out John Christopher by name: “Down with John” and “Dump the dumps.”

Rita Ashford: The trucks still rolled in and the trucks still rolled out. It didn't make a difference that we were out there.

Wilson Sayre: So they went bigger. One time, they borrowed a bus from First Corinthians Church, just down the road, and used it to block the entrance to the lot. Another time, a neighborhood elder named Rosie Lee Brown actually laid down in the street in front of the trucks.

Rita Ashford: And Rose laid down in the driveway. She was gonna stop the trucks from coming in and the trucks from going out, 'cause they was still hauling in the rocks and they were still hauling out the concrete. Baby, that old lady was a warrior, I’m gonna tell you. And she actually—that was how I got my feet wet.

Wilson Sayre: This protest attracted the attention of the police, who showed up at the lot—but not to stop the illegal dumping.

Michelle Ashford: They were saying it was private property and stuff like that. And they were really like, they were going to arrest her, because she wouldn't move.

Wilson Sayre: While residents were literally laying in the street, the lawsuit that was supposed to stop John Christopher was still dragging on. Remember, there had been a fight over the definition of waste, and twice a judge had decided not to halt the dumping.

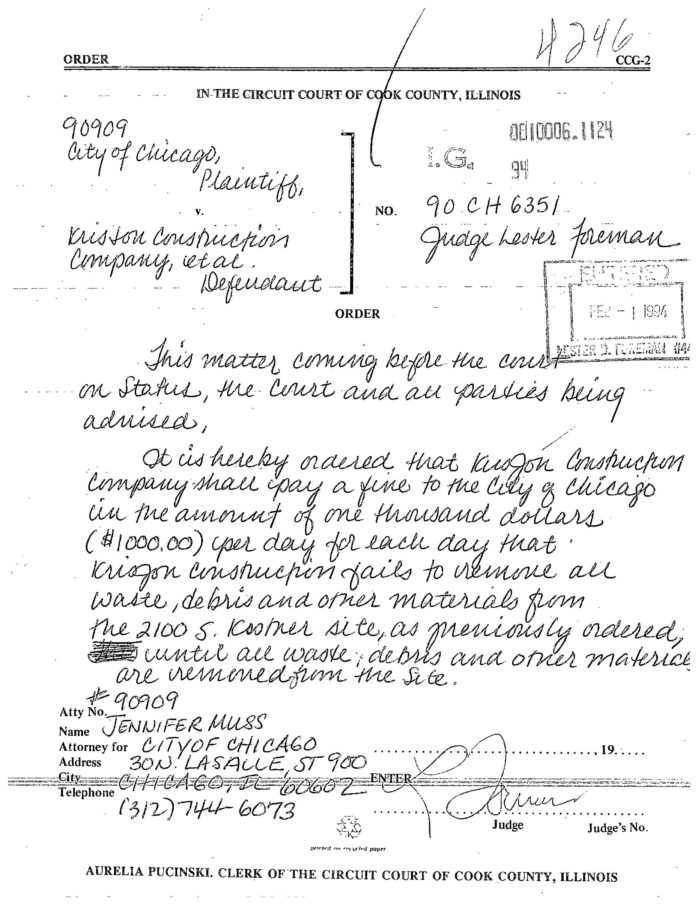

But finally, in February 1992, the court ruled against John Christopher. All of his “material” was, in fact, waste, meaning his dumps were illegal and had to go.

But the victory would prove to be hollow. Because there was still the question of how to clean up the dump.

In March of that year, the court held a hearing to rule on the cleanup—who should do it, and how long it should take.

Judge Foreman: The order of this court will be as follows.

Wilson Sayre: We don’t have a recording of what happened at this hearing, but as we’ve done before, we had some actors dramatize scenes from court taken verbatim from transcripts. You’ll remember some of the players.

Susan Herdina: Your Honor, may it please the court.

Wilson Sayre: This is Susan Herdina, a lawyer for the city of Chicago.

James Graney: Sir, would you state your name for the record, please.

Wilson Sayre: James Graney, the lawyer for John Christopher, the man responsible for the dumps, and...

John Christopher: John Christopher

Wilson Sayre: The man himself.

And one new voice—who could not have made his disdain for this case—any more apparent. Judge Lester Forman.

Judge Foreman: If this case goes to the Appellate Court, this court will be ousted of jurisdiction. I don’t know that I have said my prayers enough to hope that that could happen to me.

Wilson Sayre: Judge Foreman wasn’t the only one tired of this case.

Susan Herdina: Your Honor, you and all of us have lived with this case for quite a few months. I know I don’t need to remind you about that. The primary question here today, Your Honor, is how long this cleanup should take.

Wilson Sayre: How long the residents of North Lawndale would have to continue living next to this dump.

John Christopher’s lawyer first tries to argue that his client can’t afford to clean up the site unless he’s allowed to keep dumping. If he’s not earning money off the dumps, then he won’t have money to pay for the cleanup.

Judge Foreman: Counsel?

James Graney: Thank you, Your Honor.

If this man is not there to continue to operate that site … to maintain the premises … all that would result in is putting the man out of business. It’s not going to result in the materials being moved, and if this man is not there to continue to operate that site, you’re going to have a worse situation now than what we’re trying to resolve.

The city of Chicago won’t clean it up. If we immediately put him out of business, no one’s going to clean that site up. I submit to the court that my client doesn’t have the financial wherewithal to clean up this site.

Wilson Sayre: Judge Foreman doesn’t buy this argument though. He’s already ruled that the dumps are illegal. The dumping must stop. So Judge Foreman rejects this request, and the case moves on to the cleanup.

And notice, in what follows, that the debate over how quickly the dumps should be cleaned up doesn’t take into account in the people with asthma, or damage to people's homes or danger posed to elementary school kids.

Instead, the city proposes a timeline for the cleanup that’s all about trucks and weights and money. They factor in how much the average dump truck can hold (22 tons) and how long it would take to fill up a truck (roughly seven minutes) and how many working days there are in a year (255) and how stuff there was on the site (approximately 31,425 truckloads).

The city wanted the judge to force John Christopher to clean up the dumps within 13 months.

But John Christopher argues that even that wasn’t enough time. He wanted at least to double that—a minimum of 26 months. When John Christopher gets up on the stand to testify, he says he doesn’t have the equipment on which the city based its timeline.

James Graney: Defense calls John Christopher to the stand. Sir, would you state your name for the record, please.

John Christopher: John Christopher

James Graney: All right, sir. And what’s your relationship with KrisJon Construction Company?

John Christopher: I’m the president of KrisJon Construction.

James Graney: How many 20-ton trucks does KrisJon Construction Company own at the present time?

John Christopher: Ten.

James Graney: And the capacity of those is 20 tons?

John Christopher: Yes, sir.

James Graney: All right. Now KrisJon Construction Company—

Judge Foreman: Does he have any 24-ton trucks?

James Graney: Do you have any 24-ton trucks, sir?

John Christopher: No.

Judge Foreman: Does he have any other trucks besides these?

James Graney: Do you have any other trucks besides these ten 20-ton trucks?

John Christopher: I only have pickup trucks besides that—three-quarter-ton pickup trucks.

Wilson Sayre: After hearing all this back and forth, the judge finally rules on how much time John Christopher will have to clean up the site.

Judge Foreman: The order of this court will be as follows: Unquestionably, these are matters where you must balance the public interests against the private interests of the business person, corporation, or entrepreneur who is operating a business. That is unquestionably a difficult balance.

I think it would be a very narrow process on the part of this court to take a very short-sighted and overly-aggressive attitude toward this cleanup, because I believe that the purpose of this court should be to accomplish a result, rather than to come up with a judgment that looks good and appears to be very strict at this moment, which would be nothing more than giving somebody a chocolate-covered aspirin. It will taste sweet, but be sour going down.

By the city’s own estimate at the Kildare site, we are talking about 31,425 truckloads. Stop and think of what a line would look like with 31,425 trucks lined up. That perhaps would be a line that would take a road from one end of the city to the other. We are talking about an accomplishment of what I consider to be a gigantic task.

The defendant will have 30 months within which to remove from this site. I believe that that is a reasonable length of time that takes into consideration the magnitude of the number of truckloads that we’re talking about.

Wilson Sayre: Thirty months.

John Christopher lost the case. But he would have 30 months—two and a half years—to clear out of North Lawndale. Longer than he had asked for, and longer than he’d been there in the first place.

And again, Judge Foreman’s decision was all about John Christopher and his business and his money. None of it was about what would happen to North Lawndale residents if the dumps were not cleaned up quickly.

Even with this very lengthy timeline—one that gave John Christopher more than what he’d asked for—he did the opposite of cleaning up the mountains. John Christopher did exactly as he had threatened to do when residents first confronted him at the lot.

Henry Henderson: Well, John Christopher basically disappeared.

Wilson Sayre: Henry Henderson, the city lawyer, helped initiate the suit against John Christopher. By the time the case wrapped up, he’d become commissioner of a brand new department within Chicago’s city government: the Department of Environment.

The department was created in part to tackle big, intractable problems like John Christopher’s dumps. But despite Henderson’s new role as the head of a city agency, he seemed unable to pin John Christopher down.

Henry Henderson: You know, he popped up in other locations with a different identity. He was John DeVito for a while. And you know, occasionally people would have, catch sight of him. Occasionally you’d get, one of our inspectors would say, "I saw John Christopher, and he drove off," you know. He was very good at being being scarce.

Wilson Sayre: Unable to find John Christopher, the city couldn’t force him to conduct the clean-up, or collect any fines him for failing to do so.

And now the city was stuck with more than 31,000 truckloads of debris that it couldn’t get rid of.

Henry Henderson: Now we have to figure out how to clean it up? How do we finance something like this?

Robin Amer: The city failed to hold John Christopher accountable.

1992 passed, then 1993, then 1994. Deyki Nichols moved from fourth grade to fifth to sixth. And John Christopher’s illegal dumps still marred the landscape.

And then, the city heard about another dump in another neighborhood. A mostly white, mostly well-off neighborhood.

And the story of that dump played out very differently than the one in North Lawndale.

That’s after the break.

ACT 2

Robin Amer: Last time on The City we talked to Conrad Henry—the son of former alderman Bill Henry.

And we asked him if the dumping that had happened in North Lawndale’s 24th Ward could have happened elsewhere else.

Conrad Henry: It definitely wouldn’t have been dropped in the First Ward. It wouldn’t have been in the 14th either. Forty-Seventh Ward it would have been gone.

Robin Amer: Each of these wards was either affluent or politically connected or both. And in the case of the 47th Ward, majority white.

Given Chicago’s racial divisions, at first, it seemed unlikely to me at least at first that a dump like the ones that popped up in North Lawndale would ever pop up in a wealthy white Chicago neighborhood.

But our reporter Wilson has been reporting on a dump that actually did show up in a white neighborhood in 1994.

So now we get to test out Conrad Henry’s theory that a dump in say, the 47th Ward, would be gone [snaps] like that.

Let’s go back to Wilson.

Wilson Sayre: There’s the sign: Lane Tech College Prep, “School of Champions.” Wow! It looks like Yale, like an Ivy League university. It has red brick and gothic architecture. You’d never know that there were piles that you couldn’t see over.

Wilson Sayre: The dump was right next to one of Chicago’s most prestigious public high schools: Lane Tech.

This school pulls in some of the highest performing students from around the city and boasts an impressive roster of alumni. Chicago artist Theaster Gates went to Lane Tech. President Bill Clinton’s chief of staff John Podesta went there. Also, a surprising number of pro-baseball and football players graduated from the school.

Vivian Rankin, whose youngest daughter was a junior at Lane Tech at the time, remembers when the dumping first began.

Vivian Rankin: All of a sudden there were 50 trucks an hour pulling in and out. Huge semis were coming in. They would come down one street and go out another. And just dump this stuff.

Wilson Sayre: I found a video online of what happened at Lane Tech in 1994. I watched it with Vivian Rankin and her husband, Bill Rankin, who used to teach at Lane Tech.

Bill Rankin: OK, we got Lane Tech there in the distance. The stadium and then the school.

I showed them both the video. It’s basically a home movie we found on YouTube, shot by a local resident. In the video, you can see a two-story mountain of debris next to this high school. Truck after truck turns onto the street beside Lane Tech. The trucks would drive into the lot next to the school, and dump their cargo.

The same kind of stuff that was dumped in North Lawndale—broken pieces of concrete, dirt, and other construction debris.

Bill Rankin: And you can see the pile of rock to be crushed with the bulldozer on top just west of that stadium.

Wilson Sayre: Is that how high it got, or did it get higher than that?

Vivian Rankin: I think it got higher than that.

Bill Rankin: It could have been, yeah

Wilson Sayre: The piles grew to be level with the top of the bleachers at the football stadium. They were so close it almost looks like you could have walked off the top of the grandstand, right onto the hills of debris.

At the time, Mr. Rankin was a member of the school council, which met twice a week in the mornings. And soon after the piles showed up, teachers and parents started to complain about the dust and the shaking and the trucks.

Bill Rankin: You know, because this was a time when the school was not air-conditioned. Windows were opened. And it was the dust and the noise and that the teachers were complaining about, and the kids, they were aware of it as well.

Vivian Rankin: For me, the major issue was health. It's health and safety of 5,000 kids. So even if they don't have asthma today, could a six-month exposure to that crippy crap create an issue? We don't know.

Wilson Sayre: These were the same health and safety concerns Delores Robinson—and Michelle and Rita Ashford and so many others—had over in North Lawndale.

And again, this was 1994, at which point North Lawndale had been dealing with all this for almost four years.

The operation next to Lane Tech was run by a company called Plote Construction.

In North Lawndale, John Christopher had gone to Alderman Bill Henry for permission to set up his rock crushing operation. And here, Plote had gone to the two aldermen whose wards bordered the school: Eugene Schulter and Dick Mell.

I reached out to both of them multiple times for an interview. Neither responded.

Plote was repaving the Kennedy Expressway, a major highway running from downtown to O’Hare Airport. The highway passed a mile and a half from Lane Tech. And so Plote was trucking in broken up pieces of the old highway to this lot next to the school. They were crushing it into gravel, and then carting it back out to the highway to repave the road surface.

Remember, repaving the Kennedy and other highways was part of then-mayor Richard M. Daley’s so-called Renaissance. Some of the debris from those projects ended up in North Lawndale. And now, beside Lane Tech.

Word of Plote’s dump/rock-crushing operation and “this crippy crap” next to a school made its way to the city’s Department of Environment, to the desk of Henry Henderson.

Henry Henderson: Yeah. Serious outcry from neighbors. Serious complaints from parents of people at Lane Tech. Kids were having real problems with breathing. The neighbors were not happy with the truck traffic and were outraged by what was happening there.

Wilson Sayre: Henderson knew Plote didn’t have a permit to dump there because he’d have been the person to issue one.

So Henderson grabbed a colleague. They hopped in a car and drove up to Lane Tech to see what was going on. They saw all these piles of debris and the trucks coming in and out, and the crusher crushing rocks into gravel.

Henry Henderson: And so I said, you know, “Look, I'm commissioner of environment, and I have the authority, duh duh duh.” And we said, “You've got to stop this.” They basically said, “You know, go pound crushed rock where the sun don't shine.”

Wilson Sayre: So Henry Henderson called the cops. Five squad cars showed up.

Henry Henderson: And the police came over and said, “Stop it. Immediately.”

Wilson Sayre: Remember, the police had also been called to North Lawndale. In that case, the police were there to protect the dumpers.

But when the police came to Lane Tech, they stopped the rock crushing.

Henderson did give Plote a temporary permit to keep dumping though—at least until they could figure out where else the stuff could go.

When asked why he’d give Plote a permit, even a temporary one, Henderson told the press, "I couldn't shut down the Kennedy. People would be outraged by the inconvenience."

But the Rankins, and other Lane Tech parents and students wanted the piles gone.

So they did exactly what parents and students had done in North Lawndale: they protested. Here’s Bill and Vivian Rankin again.

Bill Rankins: Some of the kids actually laid down in front of the trucks. Didn't take very many. I think they were mostly football players that I recall anyway.

Vivian Rankins: Enough to be pesty. It doesn't take a lot.

Wilson Sayre: WGN Channel 9, a local TV news station, was just two blocks away from Lane Tech. The Rankins remember students from the school’s video club filming the dump, and then giving the footage to the station. Pretty soon, the Lane Tech dump was all over the news—both TV and the papers—in a way that North Lawndale had never been.

Bill Rankin: Bad publicity is something that politicians just don't like. And so, if you can get that and if you can get a newspaper or a TV station, then usually you can stop it.

Wilson Sayre: Outcry from students and parents and the media resulted in a community meeting. Henry Henderson was there. Bill and Vivian Rankin were there.

Bill Rankins: Plote was there. The aldermen were there.

Vivian Rankin: The kids came out, parents came out, community groups, school groups, health groups. The American Lung Association was there. The American Cancer Society had representatives that came to meetings.

Wilson Sayre: These families were able to get national organizations, people with clout and power, to show up in support of their cause.

Inside Lane Tech’s fancy art deco auditorium, person after person got up and told Plote, and the aldermen, that they wanted the dumps gone yesterday.

At first, Plote pushed back.

Bill Rankin: Well, I think the the Plote company tried to say that what they were doing was not harmful in any way.

Wilson Sayre: But then, one of Bill Rankin’s friends who had shot a video of the dump played it for the audience.

Bill Rankin: It showed trucks dumping the stuff, showed the dust clouds coming up and the banging of the crusher. Showed all of that.

Wilson Sayre: We reached out to Plote to ask them about this incident, but the company declined to comment.

As for the aldermen who’d originally given Plote permission to be there, Dick Mell, dug in his heels and continued to support the operation. At the time, he was reported to have said that the Kennedy construction project was already dirty and noisy, so why worry about a few more trucks?

But the other alderman, Eugene Schulter, cracked under the pressure and switched sides, saying, “Under no circumstance will I find this an acceptable activity.”

And with the protests and the media coverage...

Bill Rankin: The jig was up.

Wilson Sayre: News of the Lane Tech dumps went all the way to the top—to Mayor Daley himself. A few weeks after that community meeting, at the recommendation of Henry Henderson, Daley announced that he would be cracking down on rock crushing sites that “come in and environmentally destroy the community.”

The mayor fancied himself an environmentalist. Daley would later put a green roof on top of City Hall. He was, after all, the one who created the Department of Environment in the first place—and the one who had hired Henry Henderson to run it.

Daley had never said a word publicly about the dumps in North Lawndale. But here he personally ordered a shutdown of the site next to Lane Tech.

And Plote didn’t even try to fight the mayor, at least not publicly.

Quietly, seemingly overnight, Plote loaded up truck after truck and carted the mountains of debris away from Lane Tech.

Robin Amer: To get rid of the dump next to their school and homes, Lane Tech parents and teachers wrote letters, made calls, organized protests.

In other words, they did exactly the same things people had done in North Lawndale with very different results.

The cries of Lane Tech’s parents did not fall on deaf ears. Their complaints were not bogged down by endless court proceedings. Apparently, when you’ve got the mayor of Chicago on your side, you don’t even need to go to court. The dumps in North Lawndale plagued the neighborhood for years the Lane Tech dump was gone in a matter of weeks.

In other words, the city listened to Lane Tech and took action in a way it had not in North Lawndale.

Why? That’s coming up after the break.

ACT 3

Robin Amer: The situation at Lane Tech and the situation in North Lawndale could not have played out more differently. If you ask why, activist dad Bill Rankin says it’s because he and his neighbors did something different. Something more effective than what residents in North Lawndale must have done.

Bill Rankin: If you're going to do something that makes people change, you have to do something that that they have to react to, and you know, you can write a letter and they'll ignore it. You can go stand by their desk, and as soon as you leave, they’ll ignore you.

Uh, you know, he can make telephone calls, but the big thing is that they have to react.

Robin Amer: We know that Mr. Rankin is wrong. North Lawndale residents did the same things that Lane Tech parents had done. But he’s also right in the sense that the powers that be did not react to North Lawndale the same way they did to Lane Tech.

Wilson looks at why.

Wilson Sayre: In segregated Chicago, "North Side" is often used as shorthand for the white side of town and "South and West Sides” for the black and brown neighborhoods. It’s an oversimplification, but it’s used all the time.

Reporter Ben Joravsky, who we heard from in our last episode, reported on the Lane Tech dump in 1994. Joravsky says residents on the North Side—like those who lived near Lane Tech—have come to expect more from the city.

Ben Joravsky: When suddenly North Siders got a little taste of what it's like to live on the South or West Side, man. They didn't, they weren't happy. And notice the difference in how the city reacted on, we're not going to put up with that. That’s the difference between entitlement. You know, that's the difference between a city that responds to certain constituents and one end of town, and they don't respond to constituents on the other end of town.

Wilson Sayre: Joravsky says—and the record makes clear—that it wasn’t what residents did that made the difference. It was how city power brokers reacted.

When Lane Tech parents complained, city officials came out quickly. The TV news media took notice. When the police showed up, they were there to stop the dumping instead of protect the dumpers. Pressure from parents forced Alderman Schulter to take their side. When community meetings were called, national organizations showed up to support the cause.

And Mayor Daley himself stepped in to shut down the dump.

In other words, the Lane Tech community—mostly white, mostly well-off—had political power. What in Chicago, we call clout.

So now we need to revisit our “blame list.” Because some of the people on that list are power brokers who reacted very differently to the pleas from North Lawndale parents like Ms. Ashford, and those of Lane Tech parents, like Mr. Rankin.

And we should start with the press and reporters like Ben Joravsky. His piece for the Reader about Lane Tech back in 1994 was called “Crushing the Kennedy: The story of a really stupid idea.”

Wilson Sayre: You wrote about the Lane Tech stuff. Did you ever write about the dump in North Lawndale?

Ben Joravsky: I don't think so. Uh, no. I um, I never wrote it. I didn't follow it. Most of the stuff I did was, uh, like, people would call me with story ideas. If someone had called me, it would have been totally different. I would have liked plugged in. I would have been like, “Oh, yeah, I got a person there…”

Wilson Sayre: Some news outlets, namely black-owned ones like the Chicago Defender, did write about the North Lawndale dumps. But no TV crews made it out there. There wasn’t a TV station just across the street. And historically, the Chicago press corps has done a poor job of comprehensively covering the South and West Sides.

Robin Amer: So back to our blame list. Next up we have to go to Henry Henderson. In both North Lawndale and at Lane Tech, he personally drove out to inspect the dumps. But at Lane Tech, he brought the cops with him and shut down the dump immediately.

I asked him about it when we spoke.

Robin Amer: The thing that really jumped out at me was the picture of you showing up at Lane Tech, confronting the guys from Plote, and then bringing the cops in to say, “No, you have to stop this immediately.” And I have to ask you, did you ever do that in North Lawndale? Did you ever go to North Lawndale with the police escort to confront John Christopher and say, “You have to stop this now?”

Henry Henderson: You know, I did not bring the police. Because—I don't know why I didn't bring the police. But the fact is that those experiences informed what we needed to do subsequently. So it’s like, how do you prosecute these things better? And so you learn by doing.

Robin Amer: Henderson told me, essentially, that he learned his lesson the hard way. The court battle proved that if you did not stop the dumping right away before it got bad, then the dumps would get so big that you’d be facing a monumental problem that could not be stopped or fixed overnight. Four years later, he applied those lessons to Lane Tech.

Wilson Sayre: Well, except there’s no reason Henderson couldn’t have called the police to arrest John Christopher. Especially once he was in violation of the court order. At this point, the city’s response is basically, “Oh well, we just can’t find him.” To me, it feels like Henderson felt the pressure of Lane Tech parents more, and therefore he reacted more quickly.

And then there’s they guy Henderson reported to: the mayor.

Ben Joravsky: Where was Mayor Daley, Mr. I Love Trees?

Wilson Sayre: Again, Ben Joravsky.

Ben Joravsky: Leave Henderson alone. He’s just a bureaucrat. Daley was the guy. Where was Daley? Why wasn't Daley looking out for the interests of the kids?

Wilson Sayre: And although Henderson had a lot of power as a city commissioner, Mayor Daley had more. A lot more. You can go through the courts, plead with government agencies. Or you can get Daley's attention, and he can snap his fingers and get it done.

Take the story of Meigs Field. It’s almost Chicago lore at this point. It happened years later, but shows how Daley behaved when he cared about something.

Meigs Field was an airport runway built on an artificial peninsula that stuck into Lake Michigan. It was right next to Soldier Field, where the Chicago Bears play, and the natural history museum and the planetarium—prime real estate. And Daley wanted a park there instead of an airport.

So he sent construction workers out in the middle of the night and tore a big “X” in the runway.

Ben Joravsky: Mayor Daley went to Meigs Field in the middle of the night and tore up a runway, said “Fuck you” to the federal government, “I'll see you in court.” Made up an excuse for it, saying, “Oh, terrorists are gonna knock down our city.” And yet we can't get a dump off of land and our city? I don't think so.

Wilson Sayre: In other words, Ben says, if Daley wanted something done, it got done. If he had wanted the dumps in North Lawndale gone, they would have been gone.

People in Chicago government who could have come out in the middle of the night and dealt with the dumps in North Lawndale never showed up.

Ben Joravsky: They didn’t care about the people living in that neighborhood. They didn't care about that dump. They allowed that dump to exist for years. This dump got—one month it was gone on the North Side! So I don’t buy it.

Wilson Sayre: Mayor Daley simply said of Plote, the construction company, “They have to find another site. That’s their problem.”

Daley did not do the same for North Lawndale.

Robin Amer: We reached out to Daley for comment, but he never responded to our requests.

Although Henry Henderson had not been able to catch John Christopher, and despite the fact that Henderson’s boss seemed not to care enough to personally intervene, Henderson told us that during this time he had also been trying to get help from the state and federal governments to stop and then to clean up the North Lawndale dumps.

Eventually, in late 1994 and early 1995, the state and federal Environmental Protection Agencies finally came out to North Lawndale to clean up the dumps.

This could have been the end of our story. But it isn’t.

Over the years, John Christopher’s dumps had attracted more than just construction debris: fly-by-night dumpers had left behind these 50-gallon drums of silver goo and red enamel and other mystery chemicals. Plus, old roofing material, tires, carpet, window frames—even cars.

So when the Illinois and U.S. EPAs came to clean up the dumps, this was the stuff they were interested in.

The U.S. EPA declined to talk to us, but a representative from the Illinois EPA who was involved in the cleanup told us that the agency was more concerned about the hazardous material than what they called the “clean construction debris.”

So even these environmental protection agencies were not interested in the six stories of rubble.

They were not interested in removing the mountain—the mountain that the Ashfords believe gave their family and neighbors asthma, the mountain that Rosie Lee Brown had lain in the street to protest, the mountain that Deyki Nichols's little brother almost lost a finger to. The environmental agencies did not see the mountain as their problem.

They walked away, leaving almost all of John Christopher’s mess behind.

So Henry Henderson made one more call—to a friend of his who worked for the Department of Justice.

Henry Henderson: Saying, you know, “We're having a real hard time. This John Christopher is much larger than what we can do. And we think that this is a larger criminal endeavor here. And we really need some help.

It was clearly before I knew of John Christopher’s relationship with the federal government.

Robin Amer: The federal government. John Christopher wasn’t just a shady waste hauler. He was working for the federal government undercover.

That’s next time on The City.

CREDITS

The City is a production of USA TODAY and is distributed in partnership with Wondery.

You can subscribe to the show on Apple Podcasts, NPR One, or wherever you’re listening right now. If you like the show, please rate and review us, and be sure to tell your friends about us.

Our show was reported and produced by Wilson Sayre, Jenny Casas, and me, Robin Amer.

Sam Greenspan is our editor. Ben Austen is our story consultant. Original music and mixing is by Hannis Brown.

Jennifer Mudge, Chris Henry Coffey, David Deblinger, and Michael Cullen starred in our re-enactments.

Additional production by Taylor Maycan, Isobel Cockerell, and Bianca Medious.

Chris Davis is our VP for investigations. Our executive producer is Liz Nelson. USA TODAY NETWORK’s president and publisher is Maribel Wadsworth.

Special thanks to Misha Euceph and Danielle Svetcov, and to Gary Sigman for permission to use his film of the Lane Tech dump.

Additional support comes from the Fund for Investigative Journalism and the Social Justice News Nexus at Northwestern University.

If you like this show, you may also like WBEZ’s new podcast, On Background, which takes you inside the smoke-filled back rooms of Chicago and Illinois government to better understand the people, places, and forces shaping today’s politics.

I’m Robin Amer. You can find us on Facebook and Twitter @thecitypod. Or visit our website, where you can find a video of the Lane Tech dump and more. That’s thecitypodcast.com

PEOPLE

PLACES

READ MORE

Read Judge Lester Foreman’s full ruling against John Christopher from the hearing in March, 1992.

WATCH

This video shows the rock crusher plus the piles of concrete and gravel that grew next to Lane Technical College Preparatory High School in 1994. The operation was only up and running for a matter of weeks before then-Mayor Richard M. Daley personally called for its shutdown. The video was shot by nearby resident Gary Sigman.