S1: Episode 3

‘Mount Henry’

The neighborhood turns to a beloved ward boss—but his own agenda comes first. A man in the know offers some valuable advice on power.

Episode | Transcript

‘Mount Henry’

Robin Amer: In the city of Chicago, when you can’t get your trash picked up, or your potholes filled, the person you call is your alderman—your neighborhood representative in City Council. And so, when Johnnie Baker started seeing construction debris piling up in a vacant lot not 500 feet from her home, she called Bill Henry.

Johnnie Baker: And I'm watching trucks come in dumping the stuff. So I called his office to find out you know, what was going on. And they told me that they were just dumping there for a couple of days, and they were going to be removing it out.

Robin Amer: She remembers that happening on a Monday.

Johnnie Baker: And by Thursday, it was a tall as that building over there almost. It just kept getting larger and larger.

Robin Amer: And responses from the alderman were getting fewer and farther between.

Johnnie Baker: You know, you couldn't get Bill Henry on the phone. They didn't want to talk about it or whatever.

Robin Amer: Mountains of construction debris can’t just appear in a neighborhood without the local alderman knowing about it. And because Bill Henry wouldn’t talk about it—and didn’t seem to do anything about it—and because the dump was already the size of a department store—people in North Lawndale figured Bill Henry must be involved.

Johnnie Baker: From his conversation and his speaking he seemed like you know, he was for the neighborhood. And then, after going to his meetings or whatever, you find out it's a selfish thing.

Robin Amer: Eventually, local journalists, the EPA, and the FBI would all give the dump a nickname: Mount Henry. Its namesake, Alderman Bill Henry, allegedly cut the deals that helped usher John Christopher into North Lawndale. But the bigger story of Bill Henry shows where a neighborhood like North Lawndale sits in Chicago’s political pecking order.

I’m Robin Amer. From USA TODAY, this is The City.

ACT 1

Robin Amer: It’s October 1979, and hundreds of people are rallying in downtown Chicago. They’re gathered to “Keep County Open”—to protest the possible closure of Cook County Hospital—what was then the only public hospital in the city that would treat anyone, regardless of their insurance coverage. At the time, 90 percent of Cook County’s patients were black.

The MC introduces Bill Henry, who was then a new state rep. He wouldn’t be an alderman for another four years.

MC: Our next speaker, Mr. Bill Henry, who’s a state representative from the 21st District. Here’s Mr. Henry.

Robin Amer: A fire engine blares past.

Bill Henry: Thank you very much!

Robin Amer: But Bill Henry doesn’t miss a beat.

Bill Henry: I guess that’s by design, but they’re not going to quiet me up. [Siren passes] We’ll allow the noise to pass, ‘cause I’ve got some noise I want to put out. The noise is this: Yes, my name is Bill Henry. I’m a state representative from the West Side of the city of Chicago. I represent the poor, the old, the unemployed, the underemployed. [Tape cuts out]

Robin Amer: The tape cuts out here, but it should give you some sense of what a commanding presence Bill Henry had.

Alright, when we began reporting this story, our producer Jenny Casas started “a blame list.” As in, who’s to blame for the dumps in North Lawndale? Jenny?

Jenny Casas: Of course it starts with John Christopher, number one, for starting the dumps in the first place. And then, number two is the construction companies who actually brought in the debris into North Lawndale. But then, the blame shifts to different tiers of responsibility, so people who helped it along in small ways, or who just didn’t step up to stop it—like the judge who denied the injunction to halt the dumping. And then, of course, there’s Bill Henry.

Robin Amer: Right, so this is the local alderman. And you’ve been spending a lot of time looking into Bill Henry. So what exactly was his role here

Jenny Casas: It’s just not an easy question to answer.

Bill Henry was alderman in North Lawndale when John Christopher arrived in 1990. At the time, The Chicago Tribune reported that Bill Henry introduced John Christopher to the owner of the lot across the street from the elementary school—apparently because John Christopher told him the operation would bring jobs to North Lawndale.

But John Christopher would later tell the FBI under questioning and testify under oath that he bribed Bill Henry in order to dump there—$5,000 a month.

Robin Amer: Right. So a source in the FBI told us that John Christopher called Bill Henry “a $5,000 guy.”

And when I heard about this, I was like, oh right, OK, that’s how John Christopher was able to get set up in North Lawndale and operate for as long as he did—he was bribing the alderman. It just made so much sense when I heard that.

Jenny Casas: Well, Bill Henry died in 1992, so we’ll never get to hear his side of the story. But it’s not as simple as a crooked guy bribes another crooked guy.

Robin Amer: Alright, so Jenny’s going to pick up the story from here.

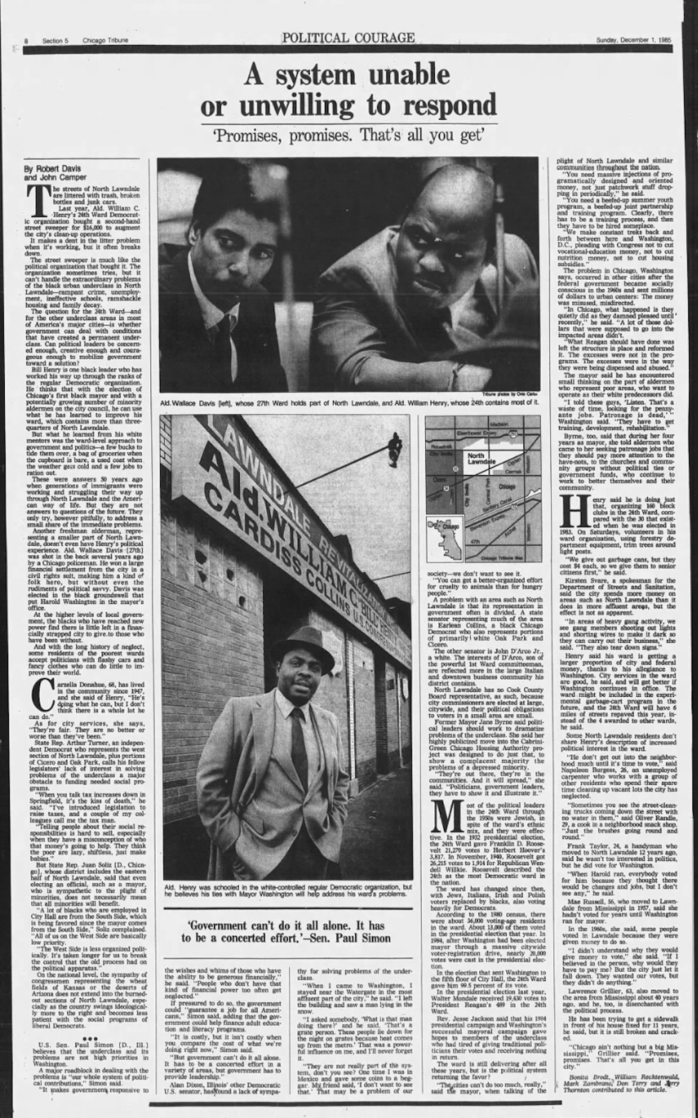

Jenny Casas: During Bill Henry’s first term as alderman, the Chicago Tribune turned its attention to the problems in North Lawndale in a whopping 36-part series.

That series would later be turned into a book called The American Millstone. The book used North Lawndale as an example of what its authors saw as a national problem: a permanent underclass they described as “mostly black and poor and hopelessly trapped.”

But North Lawndale residents and critics of the series called it “a judgment rather than a description” that stereotyped the community in harmful ways and ignored the good in the neighborhood. Here’s a representative quote:

“Today, in North Lawndale... there is no sense of community, nothing to unite them. ...They are caught up in the baseness of underclass living, casual sex, illegitimate children, crime and violence—antithetical to the teachings of religion and repugnant to those who believe in God.”

Chicago’s mainstream white press also stereotyped Bill Henry. The Tribune described him as a man with “fists the size of pineapples,” who wore “bright pastel suits”and “a gun strapped to his ankle,” who “rode to work in a stretch limousine,” and “lived on a diet of red meat and iced whiskey.”

These are all direct quotes.

They wrote about the time he won a white stallion in a game of poker, and the time he was abducted at gunpoint outside of his fiancée’s bar and then talked his way to freedom.

But in North Lawndale, Bill Henry is remembered in more nuanced ways—as a real, if flawed, person.

Gladys Woodson: I liked Bill Henry because he wasn't that sophisticated businessman. He was a street person. He was raised up on the street.

Jenny Casas: That’s Gladys Woodson. Remember, her block club wrote to Bill Henry when they were trying to get rid of the dumps. But because he was their alderman, they went to him for a lot of other routine things too. This is how she described his political philosophy.

Gladys Woodson: He would let us all know, “You can't have everything you want, and if you want something really bad, you figure out how bad you want that, and you're gonna have to give up something to get something.” That was his model. He said nobody get something for free.

Conrad Henry: He used to say, “I graduated from Concrete University.”

Jenny Casas: This is Bill Henry's son, Conrad Henry. This notion of Bill Henry as a deal maker with street smarts is at the core of his identity.

Conrad grew up helping his dad in the ward office, talking politics over breakfast. They’re fond memories because Conrad looked up to his dad.

Conrad Henry: He look dignified in the as a representative of the ward. You didn't see many people that looked like him and other elected officials in the ward. They were they were examples of African-American success in a poverty-stricken neighborhood looking for hope.

Jenny Casas: Bill Henry had gotten his start in Chicago politics on the bottom rung—working as a foot soldier for the Democratic Party. Conrad remembers being five or six, following his father around the ward, knocking on doors, coaxing neighbors to the ballot box.

Conrad Henry: His job was to get the vote out, and help people in the ward, and make sure they voted Democratic—voted for the slate of candidates that ran. And the way he would do that, I seen him, was pass out money.

Jenny Casas: Paying people to vote for a specific candidate is so illegal. But in 1960s Chicago? Totally, totally routine.

Conrad Henry: I don't know where he got the money from. But the way things went, election time, he'd have a fist full of dollars and make sure that you would come to vote. That was their strategy, to go out getting the vote, no matter what. That's how all precinct captains did in the city of Chicago. That was the regular Democratic Machine’s order of things. That was their plan. That was their strategy.

Jenny Casas: The Democratic Machine.

You cannot tell Bill Henry’s story without talking about the Machine, because it’s through the Machine that he got his political education.

The Machine worked like this: You had the mayor—the big boss—on top. Then, below the mayor were 50 aldermen—little mini-bosses—who controlled their neighborhood areas, called wards.

The aldermen and the mayor were elected, removed or kept in office through the work of the precinct captains. Precinct captains were the even smaller bosses who looked after smaller sections of each ward.

They, in turn, oversaw the foot soldiers, who were tasked with getting out the vote every election season for the party’s chosen candidates.

And if you were good at pulling in votes, you could be rewarded with a city job. It didn’t really matter how qualified you were. If you were loyal to the Machine, the Machine could get you on the city payroll, or otherwise reward you with better access to city services—like getting a tree trimmed or having a parking ticket dismissed. Favors and jobs were the lifeblood of the Machine.

And this system is great if you’re in with someone powerful. But if not, you’re probably not getting everything you’re due from the city.

Bill Henry was really good at pulling in votes—so good that eventually he graduated from foot soldier to precinct captain and was later rewarded with jobs. Early on, he was a laborer for the Department of Streets and Sanitation. But he knew how to climb the ranks. Later, he became deputy chief in the Cook County Sheriff's Department.

And eventually, the Machine slated him for elected office.

One of Bill Henry’s political role models—someone who showed what was possible for young black men within the Democratic Party—was a rising star named Ben Lewis.

Conrad Henry: Ben Lewis. That's who he wanted to be like. He looked at the power he—I guess he visualized himself to being that way. That was his aspiration as I was a kid.

Jenny Casas: Ben Lewis was the first black alderman elected in the 24th Ward. In the all-black neighborhood, he started replacing white precinct captains with black ones. In late February 1963, he won a second term as alderman by a landslide 12-to-one margin.

But then, two days later, Ben Lewis was found handcuffed to a chair, face down, in a pool of his own blood. He’d been shot three times in the back of the head.

Some people believe the Machine killed him because he was planning to run for Congress against their wishes. But more than 50 years later, it’s still an open case.

Conrad heard the cautionary tale all through his childhood—and saw remnants of the murder around the ward office.

Conrad Henry: The same chair that he was handcuffed to was still there. The bloodstains were there. It was like he was still there, ‘cause they was like, they was always talking about him as if he was just around the corner, coming in. You know, “We getting in line. We doing what these people tell us to do, ‘cause we don't want to end up like Ben Lewis.” I assume that's what my father thought about.

Robin Amer: Bill Henry learned that the Machine can build you up, but it can just as easily destroy you.

So he committed himself to the Machine and its political order.

But what are you supposed to do when that political order works against your constituents?

What should you do then?

That’s after the break.

ACT 2

Robin Amer: Alright, let’s go back to Jenny, who picks up the story of Alderman Bill Henry with a visit to one of his adversaries.

Richard Barnett: Hello? Oh yeah, what do you need?

Jenny Casas: When I met Richard Barnett in his home in North Lawndale, we were constantly interrupted by phone calls.

Richard Barnett: Could I do it later? ‘Cause I’m busy now. Thank you.

Jenny Casas: Popular guy.

Richard Barnett: Hm?

Jenny Casas: You’re a popular guy.

Richard Barnett: I’m sorry?

Jenny Casas: You’re a popular guy.

Richard Barnett: Oh, yeah! Ha.

Jenny Casas: Richard Barnett moved to North Lawndale around 1954, and lives in a two-flat with his pet parrot named Nia. He's in his 80s now, and he's been in the thick of North Lawndale's political scene since his 20s.

In his prime, Richard Barnett was a local kingmaker—but he didn’t work for the Machine.

Mr. Barnett was an independent Democrat, and an effective one, with a hand in nearly every successful aldermanic campaign in the 24th Ward after Bill Henry was out of office. He supported candidates who challenged the status quo. He hated the Regular Democratic Machine. And he hated Bill Henry.

Richard Barnett: He was Machine to the day he died.

Jenny Casas: What does that mean?

Richard Barnett: That means he was an idiot. He was slimy. He was a crook. He was anything negative that you can say. Anything he could get money from, he used his position as alderman to get money.

Jenny Casas: In 1983 Bill Henry was elected to the position he had been working towards for more than two decades: 24th Ward alderman.

But just as he was settling into his new seat of power, the political game completely changed. A change that promised of a new kind of power for neighborhoods like North Lawndale.

Singing: Chicago, Chicago! That toddlin’ town! Chicago, Chicago. . . [music distorts and fades out]

Announcer: The Machine that ran Chicago doesn’t work anymore. Yet Jane Byrne and Richie Daley are still fighting over it. Harold Washington has a different plan.

Harold Washington: While they fight over that Machine, I shall fight for Chicago by getting jobs and money from the state and federal government.

Announcer: Harold Washington.

Harold Washington: We can all win.

Jenny Casas: In 1983 Chicago elected Harold Washington, the city’s first black mayor. It was a turning point—a stunning victory for black Chicago and for independent, anti-Machine voters.

Like Bill Henry, Harold Washington had come up as a precinct captain working for the Democratic Machine. But at some point, he broke with the system. The way Harold Washington saw it, the Machine might help individual black politicians, but it would never serve black communities as a whole. He was also disgusted by the Machine’s use of patronage—the exchange of jobs for loyalty. Patronage that built careers like Bill Henry’s and his own. As mayor, he signed onto a ruling that made it illegal to hire or fire people for political gain.

Here he is talking about patronage in 1984.

Harold Washington: Well, I’m going to tell you about patronage. I went to the graveyard. I found its grave. I stomped on that grave. I jumped up and down and said, “Patronage, patronage, where are you?” And patronage didn’t answer. And you know why? It’s dead, dead, dead!

Jenny Casas: More than 99 percent of North Lawndale voted for Harold Washington in the 1983 general election. In the home of Richard Barnett, the local kingmaker, the first thing you see when you enter the foyer is a giant portrait of Harold Washington.

Jenny Casas: This is, this picture is in every living room in North Lawndale.

Richard Barnett: Oh, yeah?

Jenny Casas: Does that surprise you?

Richard Barnett: No. People came from out of town here to pick up Harold Washington buttons. I was I told you we had a thousand volunteers. Didn't pay anyone a penny.

Jenny Casas: Bill Henry had staked his entire political career on the Democratic Machine, but now the Machine was out. So, what does Bill Henry do? He flips to the other side.

Conrad Henry: My dad was a vocal supporter of Harold Washington.

Jenny Casas: Again, Bill Henry’s son, Conrad.

Conrad Henry: He dumped the regulars and went with the independents.

Jenny Casas: Arguably, given Harold Washington’s popularity in North Lawndale, Bill Henry had no choice but to support the new mayor. But citywide, there was the hope that a new black political block could make things more fair.

But that’s not exactly what happened.

The mostly white Machine politicos that had always run City Council were pissed about having a black independent mayor who challenged their power. They might have lost absolute power, but they still had the votes to block the new mayor’s agenda in City Council.

So, even with Harold Washington’s promises for a more fair Chicago, city services in lower income neighborhoods were still not as good as they were in wealthy neighborhoods. Bill Henry's ward, and many other black wards, were not getting basic city services regularly. Especially in comparison to their white counterparts.

Conrad Henry: He couldn't pull strings and get everything done instantaneous—the garbage pickup, the streets clean, the curbs done, the sidewalks repaired, you know. He couldn't do that in timely fashion like they could over there.

Jenny Casas: And so, Bill Henry took matters into his own hands. He spent $16,000 of his own money to buy a decommissioned street sweeper from the city.

Conrad Henry: It was this old city street sweeper. He painted it red, white, and blue. He put “Bill Henry,” like that, right there on it. “24th Ward alderman.”

Jenny Casas: Let me just say that again: 24th Ward residents weren’t getting the city services they paid for with their tax dollars. So Bill Henry bought a used street sweeper from the city that was failing them in the first place.

Black neighborhoods on the West Side like North Lawndale still weren’t getting their fair share.

Even with Harold Washington in office.

And four years later, just as Harold Washington was settling into his second term...

Newscast: At approximately 11 a.m. Wednesday morning, shortly following a press conference, Chicago mayor Harold Washington suffered a fatal heart attack at his desk in City Hall. The mayor was rushed to Northwestern Memorial Hospital where he was pronounced dead at 1:36 p.m.

Jenny Casas: Harold Washington died, and with him, the promise of his administration.

Ben Joravsky: Black Chicago was devastated. People have been waiting all these years to finally have an expression of black political power and maybe have some fairness in the city, and it's like, are you kidding me? Harold Washington dies in office before it could be fully expressed?!

Jenny Casas: This is Ben Joravsky. He’s been a reporter in the city for almost 40 years, namely with the Chicago Reader. He now hosts a show on Chicago’s progressive talk radio station, WCPT.

Joravsky reported on the chaos in City Hall that followed Harold Washington’s death.

Ben Joravsky: Most white people didn't vote for Harold Washington. They said the meanest nastiest things about him. So, when Harold died in 1987, suddenly it was a whole new ballgame it was an opportunity for these white politicians who have been on the outs for four years to get back in the ins. And they were going to take advantage of it.

Jenny Casas: So, once again, the tides were turning. And Bill Henry made a calculation.

When a mayor dies in Chicago, the City Council gets to choose his or her temporary replacement.

And when Harold Washington died, white aldermen realized they didn’t have a chance at the mayor’s seat. Instead, they organized around a South Side alderman named Eugene Sawyer. Sawyer was the longest-serving black alderman at the time, and a regular Democrat like Bill Henry.

But many independent voters, and Harold Washington’s base, wanted a different candidate named Timothy Evans. Evans was Harold Washington’s heir apparent, and independents believed he would carry on Washington’s progressive agenda.

Bill Henry figured that if he could help the white political establishment back into power, they would be loyal to him.

Ben Joravsky: You know, he saw his opportunity to gain political power. If Gene Sawyer was the mayor, he would have entree to the highest office in city government, maybe get some more jobs to distribute. So he saw a chance for himself to consolidate his own power, at least in his ward, and he was going to take it.

Jenny Casas: And so in the high drama of Harold Washington’s death, Bill Henry cut the deals that guaranteed a win for Eugene Sawyer. Here he is on the City Council floor the night of the vote.

Bill Henry: We need somebody can bring us together. Gene Sawyer is that man! Gene Sawyer is that man! Now...

Ben Joravsky: Somebody made an accusation: “You're making deals.”

Bill Henry: I heard one of my colleagues that I personally admire, but he don't know what he's talking about when he talking about a deal. Let's talk about the deals! Let's talk about the deal!

Ben Joravsky: And he got up: “Making deals? We was all making deals!” And that is so right! Everyone in Chicago, and ever since then, I heard that I always say, “I cut a deal. I made a deal.” ‘Cause that's Chicago: You're cutting deals.

Bill Henry: If we are honest with the people, we all was trying to deal. Everybody had a hidden agenda. Let’s tell the truth. Not a person in this City Council have the right to accuse another for cutting a deal when they was busy cutting the deals! [Explosive applause]

Jenny Casas: This was the transactional nature of Chicago politics: I do something for you, you do something for me.

I give you a couple bucks, you vote for my candidate.

I get you into office, you give me a job.

You give me a job, I give you my loyalty.

This is how it had always been for Bill Henry and anyone else who came up under the Machine.

But in this case, Bill Henry’s calculation may have been bad math.

Ben Joravsky: What happens to Bill Henry? What happens to Bill Henry after the 1987 vote to elevate Eugene Sawyer—his greatest moment on the stage as a wheeler and dealer, the pinnacle of his power, if you will? It's all downhill.

Jenny Casas: For one thing, it put him in hot water with his constituents. Bill Henry’s choice to back Eugene Sawyer was not supported in North Lawndale. Voters wanted Evans.

But also, in Bill Henry’s deal for the establishment, any favors he may have cashed in didn’t come close to achieving equal power for his ward.

So the deal wasn’t a deal. It was a gift to white Chicago—a gift I’m not sure Bill Henry knew he was giving.

Ben Joravsky: I'll put it to you this way: It was a very short lived triumph. Oh my God. It all fell apart.

Robin Amer: That’s after the break.

ACT 3

Robin Amer: Bill Henry’s support for the establishment candidate and the backlash it spurred in North Lawndale left him politically weakened. By 1990, his longtime rival, Jesse Miller, was challenging him for re-election and seemed to have a good shot at winning.

Bill Henry’s silence about the dumps only angered residents more. And they remember Jesse Miller stepping in to help them organize against the dumps.

Jenny picks it back up from here.

Jenny Casas: As if all this weren’t bad enough, in November of 1990, Bill Henry was slapped with a 24-count federal indictment. The indictment lays out almost a decade of racketeering, bribery, and extortion totaling more than $30,000. Many of the allegations involved Bill Henry taking money in exchange for helping someone get city jobs or contracts.

To North Lawndale politico Richard Barnett, these charges show a pattern of behavior. Barnett believes Bill Henry was taking bribes for everything, including bribes from John Christopher to allow the dumps in North Lawndale.

Richard Barnett: He was the person that gave them permission and got paid for dumping on that property. It was a vacant lot, you know. So he gave them an OK to dump.

Jenny Casas: How do you know it was Bill Henry?

Richard Barnett: If you own a firm, would you dump on a lot without someone to protect you? You know what you can get fined for dumping on a lot? That's a buck you wouldn't want to spend. So you had to have permission from somebody. That's what they did. They paid him.

Jenny Casas: Bill Henry would die of lung cancer before his case ever made it to trial. But he denied the allegations with his trademark bravado. Here he is on WBBM radio in December 1990, calling the federal corruption investigation racially motivated.

Bill Henry: Oh, of course, you know, I mean Jesus Christ, Ray Charles can see that. I mean, you can go into the neighborhood, you can't fool the people. The people are not stupid. They know what’s going on. They know the charges, the attack on me, was started just to, just before the election to try to smear me and smear my people, to stop progress.

Jenny Casas: Bill Henry’s son Conrad also denies the allegations of bribery, and the allegations that his dad helped John Christopher establish the dumps.

Conrad Henry: Whoever's idea was, it wasn't my father's idea.

Jenny Casas: That’s usually how our conversations go. I ask him if his father took bribes from John Christopher, and he starts with the hard denial. Then, he backs it up.

Conrad Henry: My thing is, my dad had no wealth. He lived off of a public servant’s salary. We didn't own the building we lived in. We was renting on the second floor.

Jenny Casas: And then, he speculates. If his father did cut a deal with John Christopher, there must’ve been a reason.

Conrad Henry: I know my dad wanted to do what he could, you know? And like I said, if he could—he probably, his hands were probably cut. He couldn't do anything. Nobody would help him.

Jenny Casas: He remembers his father being almost melancholy about the dumps. If he had made a deal, it wasn’t one he was proud of.

Jenny Casas: How did your dad feel about it being called Mount Henry?

Conrad Henry: He was not proud of it. The first time he said it, we was in the car, we was driving past, and he said, “They called that Mount Henry.”

And I'm like, “What?” That’s when I said, “What?”

He was like, “Yeah.”

He was not smiling. He was quite subdued, quite sad about it in a lot of ways. It was like he couldn't get nothing done about it. It was like he'd been duped. Like he’d been tricked. Like he had been used to dump that there.

Jenny Casas: If Bill Henry did cut a deal with John Christopher, thinking the “rock crushing operation” would bring jobs to North Lawndale, then in a way, it’s almost the same miscalculation Bill Henry made when he helped put Eugene Sawyer in office.

Both were deals intended to benefit him—but also, ones he might’ve thought would ultimately benefit the ward. And both times, he was wrong.

In 1991, Bill Henry was voted out of office. And he died a year later.

Still the mountains of rubble and dirt grew in North Lawndale. Even under Jessie Miller, Bill Henry’s successor.

Conrad Henry: I just thought everything would work out.

Jenny Casas: Why did you think that?

Conrad Henry: I always thought that downtown, City Hall, would do right by the people. And that they would help us with this mountain of debris. You know, I didn't understand what was going on. But in retrospect I understand now.

Jenny Casas: What do you mean? What do you understand now?

Conrad Henry: Well I mean, they didn't think of the ward. They thought of the people in 24th Ward as second-class citizens. Their priority was their wards. The people that drove the bus that ran the political machine in Chicago, they cared about their neighborhoods.

Jenny Casas: Harold Washington tried to transform this system—to evenly spread resources, and power, across the city. But after he died, the Loop had its Renaissance with shiny new buildings and parks and public art. And North Lawndale got the broken pieces of what used to be.

Again, reporter Ben Joravsky.

Ben Joravsky: And I can remember interviewing people as long ago as the ‘80s—black people from the West Side, saying, “This is all part of a larger plot to let our areas just fall apart so that they can sell the land to white people.” And at the time, I was like, that sounds pretty far stretched.

But at some point in the ‘90s, I said, you know what? It was like, he was right, and I was wrong, and even if it is not a systematic plot, it's sort of like what's happening. They're letting it happen, whether they intend to do it or not. They're letting it happen.

Jenny Casas: Even Bill Henry talked about this:

Bill Henry: Any black person in this country that will stand up to wrong, that would stand up to the people that’s trying to come in and take the land, and move the folks out of there, any time a black man stand up to that, he must expect to be attacked.

Jenny Casas: And so, after whom, or what, should this dump have been nicknamed, if not Mount Henry? Mount Chicago Democratic Machine? Mount Apathy? Mount Racism?

Conrad Henry: This ward? They didn’t care. The 24th Ward was like a dumping ground for them.

Jenny Casas: So you feel like if something like this happened in a different ward, it would have been cleaned up, or it would have been handled differently?

Conrad Henry: Yep, sure, would have. They wouldn't have dumped it in the 11th Ward...

Jenny Casas: Daley’s ward.

Conrad Henry: It definitely wouldn't have been dropped in the First Ward...

Jenny Casas: Where the Loop was.

Conrad Henry: …It wouldn't have been in the 14th either...

Jenny Casas: Home to one of Chicago's most powerful and longest-serving aldermen.

Conrad Henry: …Forty-Seventh Ward it would have been gone.

Jenny Casas: A predominantly white ward with strong ties to the Daleys.

Robin Amer: And also, in this case, not a hypothetical. Because the wealthy, white 47th Ward was exactly where the dumpers were heading next.

That’s next time on The City.

CREDITS

Robin Amer: The City is a production of USA TODAY and is distributed in partnership with Wondery.

You can subscribe to the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you’re listening right now. If you like the show, please rate and review us, and be sure to tell your friends about us.

Our show was reported and produced by Wilson Sayre, Jenny Casas, and me, Robin Amer.

Our editor is Sam Greenspan. Ben Austen is our story consultant. Original music and mixing is by Hannis Brown.

Additional production by Taylor Maycan, Isobel Cockerell, and Bianca Medious.

Chris Davis is our vice president for investigations. Scott Stein is our vice president of product. Our executive producer is Liz Nelson. The USA TODAY NETWORK’s president and publisher is Maribel Wadsworth.

Thanks to our sponsors for supporting the show, and special thanks to Misha Euceph, Danielle Svetcov, and Bill Zimmerman.

Archival footage was provided by WBBM Newsradio 780 and 105 point 9 FM, Media Burn, Chicago Public Library, and the Bob Crawford Audio Archive at the University of Illinois-Chicago.

Additional support comes from the Fund for Investigative Journalism and the Social Justice News Nexus at Northwestern University.

If you like this show, you may also like WBEZ’s new podcast On Background, which takes you inside the smoke-filled back rooms of Chicago and Illinois government to better understand the people, places, and forces shaping today’s politics.

You can find The City on Facebook or Twitter @thecitypod. Or go to our website, where you can see photos of Bill Henry in his youth, and more. That’s thecitypodcast.co

PEOPLE

READ MORE

The page below is from the Dec. 1, 1985, edition of the Chicago Tribune, with one of the articles featured in the “The American Millstone” series that highlighted then-24th Ward Alderman Bill Henry. The Tribune would later turn the series into a book by the same title, which you can read in its entirety here.

When The City team was reporting this episode, a question we kept circling back to was: whether or not Bill Henry took the bribes to allow the dump into North Lawndale — couldn’t he have done more as the alderman to support residents to get rid of it?

Right as we were closing the episode, we found a response from the Department of Consumer Services.

Bill Henry’s office had sent a complaint about a dust nuisance near the dump. The response from the city (document below) shows that inspectors didn’t believe there was a dust nuisance. The city also attached with their response some of the permits given to John Christopher’s companies for operating on the site.

John Christopher would later tell the FBI that he frequently paid off any city workers who came by the dumps to get them to leave.

The document below is a page from a partial FD-302 report, which details what John Christopher told the FBI under questioning about the bribes he was allegedly paying to public officials, including then-24th Ward Alderman Bill Henry.