S2: Episode 4

West World

We go east of the city, where wild horses roam and business is booming. City boosters say Tesla is driving New Reno, but the truth is darker and more complicated than it first appears.

Episode | Transcript

West World

Robin Amer: Hey everyone. Just a reminder that because this season of The City is about strip clubs, it won’t be suitable for everyone, especially kids. This episode contains explicit language, including explicit conversations about sex.

Production team member: Previously on The City…

Mayor Hillary Schieve: We are truly rebranding this city, and companies like Tesla, Amazon, and Apple are all building and investing right here.

John: I've seen the entire crew marching every morning out of Harrah’s and out of Circus, marching over getting on the shuttles to get bussed out to the Gigafactories. Tesla, Panasonic, so on.

Bryan McArdle: As you drive through Midtown, you see all this vibrancy—these new restaurants, new small businesses popping up, and that specific strip, it just stands out. It’s, like, such a sore thumb.

Robin Amer: If you drive east from Reno about 20 miles, you leave the city behind and you find yourself in this incredible landscape, where this river canyon flows between these sagebrush-covered mountains and eventually you’ll get to the spot where the desert floor opens up a bit and those beautiful mountains give way to massive warehouses and factories.

From above, the buildings look like these big white tetris pieces just scattered among the rolling hills. Hills that have been carved up to make space for all this new construction. This is the Tahoe Reno Industrial Center and in this unlikely landscape New Reno is springing to life.

It’s where Tesla CEO Elon Musk built a giant battery factory, the Gigafactory, which churns out millions of battery cells a day. The same battery cells that power his famous electric cars.

Now, the 2014 arrival of the Gigafactory was a game-changer for Reno’s economy, bringing with it 7,000 jobs. And last fall, the state hosted a summit to celebrate that accomplishment.

Outgoing Governor Brian Sandoval sits on stage, in front of an audience of boosters and fellow lawmakers and the press, and paints a bleak picture of his state’s economy before Tesla’s arrival.

Brian Sandoval: And it was October of 2010. The unemployment rate was 14.3 percent. Nevada led the nation in bankruptcies. We led the nation in foreclosures. In October, exactly eight years ago, there was a front-page story in the Reno Gazette Journal above the fold that said “Reno: Detroit of the West.”

Robin Amer: Now though, he’s beaming with pride. Companies like Apple and Amazon have opened in the state. But none represent the New Nevada better than Tesla.

Elon Musk is on stage too, sitting next to Sandoval. Musk is wearing a charcoal suit coat, no tie, and slim-fit jeans—you know, the uniform of Silicon Valley CEOs. Sandoval launches into some friendly chit chat.

Brian Sandoval: So when you came over that hill over here and and you see this, this landscape, did you look at it and say, this is the place?

Elon Musk: Yeah. [Laughs] This is beautiful. You know, there's like ten thousand wild horses here? I mean, this really looks like something out of a, it's like the idyllic Wild West. It’s incredible.

Robin Amer: But it wasn’t just the wild horses that drew Musk here. Something much more fundamental—something much more Old Reno—influenced his decision.

Elon Musk: You know, I think this is very much the land of opportunity here. Like, feels like freedom, right here. Feels like freedom, OK? That’s good.

Robin Amer: Freedom. The same freedom that fueled Old Reno’s vice-based economy of quick divorces and legal gambling, well, it’s attractive to corporate America, too. No income taxes. Lightning fast project approvals.

But when a giant corporation can come to town and build a mega factory at a breakneck pace, things can go wrong. And just as the dancers working in Old Reno’s strip clubs face difficult working conditions, so too do the workers in New Reno’s factories.

Officer Fritz: Yes, this is Officer Fritz with the Tesla security department, 1 Electric Avenue. We are requesting EMS for a middle-aged male. He was electrocuted.

Caller: We need an ambulance. We have a female employee that her, she got her hand stuck between two modules and she's bleeding pretty bad.

Robin Amer: Tesla’s Gigafactory helped jumpstart Reno’s economy, but it came at a cost. One that New Reno boosters working hard to kick strip clubs out of downtown don’t like talking about. One that leaders who scrambled to bring Tesla here didn’t really plan for or address. One that might make you wonder whether the New Reno is really all that different or even that much better than the Old Reno.

From USA TODAY, I’m Robin Amer and this is The City.

ACT 1

Robin Amer: When Elon Musk went looking for a place to build his battery factory, he was under tremendous pressure. He had promised the world the mass production of the Model 3, an all-electric sedan that was supposed to be somewhat more affordable than the luxury sports cars his company had been making.

He needed a factory fast. So he needed a place where he could build it with as little red tape as possible. And a guy named Lance Gilman had just the spot.

Here’s our reporter, Anjeanette Damon.

Anjeanette Damon: Lance Gilman is the kinda guy who is always wheeling and dealing. Like the afternoon I went to meet him at the Tahoe-Reno Industrial Center he was a few minutes late.

Lance Gilman: I hope we didn't keep you waiting too long.

Anjeanette Damon: No, not at all.

Lance Gilman: We're sitting over in another meeting and it was spirited. So we ran close, so—

Anjeanette Damon: Uh oh!

Lance Gilman: It's fine, it worked out really well. It had a lot of energy attached.

Anjeanette Damon: Lance looks right at home in this setting, wearing a cowboy hat and bolo tie. It’s a uniform he’s adopted since moving from Southern California to Reno in the 1980s, trading the expensive tailored suits from his days as a music promoter for western garb.

Lance and his partners bought this land in 1998—more than 100,000 acres worth. That’s about seven-and-a-half times the size of Manhattan.

Today, he’s here to take me on a quick driving tour of the park.

When he and his partners bought this land, it was nothing but dirt roads and sagebrush. The corporation that owned it was actually thinking of turning it into a big game hunting park.

Lance Gilman: We had to build 300 lane-miles of road. So we put in all of the sewer, all the water, all the gas, all the fiber.

Anjeanette Damon: As we’re driving, we come across this road crew. They’ve stopped work while a guy with a bright orange sign shoos a tarantula the size of a man’s hand out of the worksite.

Lance Gillman: There's tarantulas out here. There's scorpions, there's tarantulas, there's rattlesnakes. This is Nevada desert! [Laughs] And it's all here.

Anjeanette Damon: Lance drives us up a steep dirt road to a flat knoll. From this vantage point, you can see the park’s sweeping landscape.

Lance Gillman: So we can step out here and we'll look out here.

Anjeanette Damon: He starts pointing out the park’s tenants.

Lance Gillman: So that's the Tesla building across over there to the right with the red stripe. That's a five thousand acres. The big building right below us, the largest one, is Zulily.

Anjeanette Damon: Zulily is an online clothing retailer. Its building is about five times larger than your typical Costco.

Lance Gillman: And then the guys just below us is U.S. Ordnance. Fifty-caliber machine guns. They're sitting on about $50 million worth of machine gun orders to Saudi Arabia right now. It's amazing.

Anjeanette Damon: Diapers.com, Walmart, Ebay, Petsmart. They all have giant buildings out here.

And a steady stream of semi-trucks rolls through the park, pulling into the warehouse loading docks to drop off and pick up the online purchases of millions of Americans. You know that big screen TV you ordered from the comfort of your couch after drinking a little too much wine? Or the cute shoes you bought on impulse? Or the flowers you sent your mom? They may have come through one of these warehouses.

As we’re talking, a band of wild horses wanders by, frolicking in the dirt, munching on the scrub brush.

Lance Gillman: We have about a thousand head of wild horses. The companies that are out here love them. Elon Musk has them on his Web site.

Anjeanette Damon: Yeah, Elon loves them, but many native Nevadans—ranchers especially—have more of a love-hate relationship with the wild horses. In real life, they aren’t just a living prop in a Wild West theme park. They can overgraze the land, muddy water sources.

But it’s not just the wild horses that really drew the CEOs here. The selling point is the lack of government bureaucracy—the same permissiveness that in the past encouraged the capitalization on vice. Now it’s the cornerstone of Silicon Valley’s expansion into Northern Nevada.

We head back to a small county office building in the middle of the industrial park. Inside is a tiny office.

Lance Gilman: We've done a lot of major real estate deals right here.

Anjeanette Damon: Yeah? Who's sat in this room? Any names we would recognize?

Lance Gilman: Oh sure. Tesla and Google and pretty much, Blockchains. Pretty much everybody.

Anjeanette Damon: A conference table takes up most of the space. This is where Lance helped land the Gigafactory deal.

Back in 2014, states across the country were trying to woo Tesla with huge tax incentives. It was all part of a familiar dance, states and cities launching elaborate campaigns to attract big tech companies with tax incentives and land deals. In other places, those enticements have sparked their own backlash, like when New Yorkers rose up to scuttle a $3 billion deal to bring in an Amazon headquarters.

Anjeanette Damon: But five years ago in this little room, Lance wanted to know why Tesla hadn’t yet picked a place for its Gigafactory.

Lance Gilman: Texas was offering them billions of dollars to come to Texas. And New Mexico was in the hunt. And Arizona was in the hunt. And California was offering them billions of dollars to come to California.

Anjeanette Damon: Two Tesla higher-ups scouting locations told Lance they couldn’t afford any delays in the building schedule—no pesky zoning fights, no labor-intensive environmental assessments, no lengthy permitting times.

They asked him:

Lance Gilman: Well, how fast could we get a grading permit?

Anjeanette Damon: A grading permit. It’s kind of a boring piece of paper, but it will let them start clearing the land, getting it ready for construction. Tesla needed to move the equivalent of 42 Olympic swimming pools worth of dirt before building could start.

The county’s planning manager, Dean Haymore, was sitting next to Lance in this meeting.

Lance Gilman: So Dean took a piece of paper out of his notebook and he said, “That's your grading permit. Fill in your name and you can leave here with it.”

Anjeanette Damon: Handing Tesla execs a permit scrawled on a torn sheet of paper was a symbolic move. But here in Storey County, things move almost that quickly. On average, it takes less than seven days to get a grading permit, less than 30 days to get a building permit. In many cities, it can take months, even years, to get that first permit.

Lance Gilman: Three and a half weeks later, the grading on probably one of the largest pads ever done in the United States—three and a half weeks!—I stood on a bank watching this anthill of activity going on with Yates Construction, their vice president, and he said, “Lance Gilman, this could have only happened maybe one other the place in the world today. That would've been China.”

Anjeanette Damon: Nevada: the China of the West, I guess.

But how could they possibly move that fast? In short, Lance and his partners did all the bureaucratic work up front years ago, clearing the way of any zoning hurdles way ahead of time so companies don’t have to come to town and argue for months before a planning commission.

Lance Gilman: What we did out here is not just zoning. We pre-approved every industrial project in the United States known at the time. It was all pre-approved. So if you were doing batteries, you were pre-approved. If you were doing flowers, you were pre-approved. If you were doing tires, you were pre-approved.

Anjeanette Damon: Want to build a giant battery factory? Get it up and running within a year? Pre-approved.

A few months after Tesla cleared the land for its factory, Nevada lawmakers took just two days to approve the tax abatements that sealed the deal with the company. It was the largest tax incentive package in state history.

Lawmakers were easily swayed by Tesla’s promise: the company would build its Gigafactory in Nevada, create thousands of jobs, invest millions of dollars in construction, and, in return, it would pay virtually no taxes for 20 years. In their rush though, lawmakers didn’t do any traffic studies or environmental studies or make sure the region had enough housing for all those new workers.

Even Musk pleaded for more housing at the governor’s tech summit.

Elon Musk: My biggest constraint on growth here is housing and infrastructure. [00:38:30] I think we're gonna, we're looking at creating a sort of housing compound just on the site of the Gigafactory, using high quality kind of mobile homes, which I think would be great because then people could actually just walk here.

Anjeanette Damon: Lance Gilman played a starring role in an ensemble cast of people who brought Tesla to Nevada. Another actor on that stage was Mike Kazmierski, the buttoned up former military commander who heads Reno’s economic development arm—the anti-strip club guy.

You might think these two gentlemen, Mike Kazmierski and Lance Gilman, would be allies joined by the common goal of remaking Reno’s economy.I asked Mike Kazmierski about it when I interviewed him last spring.

Mike Kazmierski: Uh, Lance Gilman is two people.

Anjeanette Damon: On the one hand, Mike says Lance is a gifted salesman—the pitch-perfect spokesman for the Wild West industrial park that nabbed the Gigafactory. On the other hand?

Mike Kazmierski: Lance Gilman is a brothel owner, um, has been called a pimp.

Anjeanette Damon: Lance squirms, even gets down right mad, if you call him a pimp. A pimp, in his view, is a criminal.

But Lance does own a legal brothel—the Mustang Ranch, one of the most famous in the country. And it’s right on the outskirts of his industrial park.

Unlike Mike, Lance doesn’t see anything wrong with the two co-existing.

Lance Gilman: Mike Kazmirski, God love him, is not a Nevadan. [00:10:15] He's not into the Nevada culture. And so if you really drill down into where Mike lives, in his world, he doesn't like online gaming. He doesn't like strip clubs. He doesn't like brothels. Mike would completely change our Nevada culture if he could.

Anjeanette Damon: In some ways, Lance Gilman has managed to straddle that divide between people like Mike Kazmierski and Reno strip club owner Kamy Keshmiri. He’s maintained Old Reno-style vice as a brothel owner, and he’s the guy who helped land Tesla, New Reno’s biggest win.

It raises another question: If Lance Gilman can bridge both worlds, why can’t they?

Contrary to popular belief, brothels aren’t legal in Reno, or even Las Vegas. But they are legal in many of the smaller counties on the outskirts of town.

Lance’s brothel is on the edge of the industrial park, but you’d never know it. It’s tucked into a quiet hillside, surrounded by big cottonwood trees. It’s just 15 miles from downtown Reno.

Unlike Mike Kazmierski, who’s repelled by Nevada’s smutty reputation, Lance Gilman relishes his role as a brothel owner. He holds business meetings at the brothel from his large round table in the corner of the lavish front room—the same room where women pair up with their customers before leading them into the back for another kind of business encounter.

This place is so integral to who Lance is and how he capitalizes on both the Old Reno and New Reno worlds, that I wanted to see it.

Lance Gilman: Good morning! Or afternoon I guess now.

Anjeanette Damon: When you first walk into the brothel, you’re actually entering the Wild Horse Saloon, a seemingly regular old restaurant and bar.

The lights are low, small tables dot the floor, and there’s a bar against the back wall. You can come here just for a beer and a burger if you want.

There’s a stripper pole in the corner. But unlike in Kamy Keshmiri’s strip clubs, it’s totally OK here to pay for sex in the back.

Anjeanette Damon: I see. You have to go behind the green door.

Lance Gilman: I'm going to take you through the green door.

Anjeanette Damon: OK.

Anjeanette Damon: We walk into what looks like a British hunting lodge: big fire going, lots of taxidermy animal heads on the walls. Lance hands us off to our tour guide, a sex worker named Cherry. She’s petite, with long-flowing brown hair, wearing a silky robe and high heels.

She shows us into a tiny room where ladies and customers come to an agreement on services.

Cherry: We take credit, debit, cash. We're totally legal.

Anjeanette Damon: Here, women are accepting credit cards for sex, when just 15 miles down the road, Reno City Council members are arguing over whether strippers should be able to perform lap dances.

Before they actually hook up, the ladies inspect their customers for any signs of disease.

Cherry: That is full of baby wipes. This is full of gloves.

Anjeanette Damon: And then it’s off to the fun. You can join a lady in her room—the one she basically lives in during her week-long shift—or spend time in one of the brothel’s more lavish theme rooms. There’s the orgy room, the jacuzzi room, the tropical Hawaii room—even a dungeon.

Cherry: You can really just let your mind run wild. There's no wrong way to enjoy a dungeon.

Anjeanette Damon: Or, you know, you can just come in for a quickie.

Cherry: I'm not kidding. Some people have, like, they're ringing our doorbell, like, ding ding ding ding ding ding ding. We’re like, “Go let that guy in. He's in a rush.” And he's like, “I have 30 minutes. I'm on my lunch break. It takes me 15 to get to Reno. Are you available?” And you're like, “OK. Yes. OK, yes.”

Anjeanette Damon: Back in the Reno strip club fight, there’s all this tension between old and new. LIke we can’t have New Reno if we don’t get rid of Old Reno entirely. But this brothel is the epitome of the sordid Old Reno ethos, and it’s alive, even thriving, on the edge of the gleaming industrial park that’s the epitome of New Reno.

In fact, this industrial park, it might never have come to be if hadn’t been for this brothel.

In the late ‘90s, when Lance and his partners were on the hunt for a good spot to develop, they were mainly looking for land.

And Storey County, even though it’s the smallest county in the state, had a lot of it. It was also desperate.

Lance Gilman: They were church mice poor. They were, as a matter of fact, they were on the brink of bankruptcy.

Anjeanette Damon: At the time, the county’s major source of tax revenue was its brothels.

But the Mustang Ranch—the single largest taxpayer in the county—was closing. The previous owner had been indicted on money laundering charges and had fled to Brazil.

The feds shut it down, costing the county about 12 percent of its budget.

The county needed someone to keep the brothel open. Commissioners turned to Lance.

Lance Gilman: I don't think there is a business in America that would generate cash flow instantly except the brothel business.

Anjeanette Damon: Lance bought the Mustang Ranch from the federal government—on eBay of all places. The county was once again rolling in brothel cash. And so was Lance.

Lance says the brothel generates a million dollars a month in revenue—money he used to help keep the industrial park afloat during the recession. The taxes on that cash also helped Storey County’s government stay afloat.

Lance’s lawyer Kris Thompson puts it this way:

Kris Thompson: And had he not done that, that magic phone call to get that Tesla deal may not have ever come.

Anjeanette Damon: Lance says he prides himself on running a classy joint—the best of the best.

In fact, he says Kamy Keshmiri could learn a thing or two from him.

Lance Gilman: You run the business quietly, out of town. You're not by a school or a church or any of the public facilities, and you stay below the sagebrush.

Anjeanette Damon: It’s true, the government isn’t all up in Lance Gilman’s business the way the city of Reno is cracking down on Kamy Keshmiri. If the Wild Orchid did a better job of “staying below the sagebrush,” Lance argues, maybe the city wouldn’t be so up in arms.

But things are never that simple. Staying “classy” is not why local government leaves Lance alone. Remember, county commissioners were the ones who asked Lance to re-open the brothel in the first place.

Also, Lance isn’t always so classy himself. Neither are the publicity stunts he uses to promote the brothel. Things like the, quote, “Hunt a Ho” game he concocted, where men chased prostitutes through the hills with paintball guns. Or when he staged a motocross event to try and set a record for, quote, “jumping the most titties in one night.”

Another big reason local government might be leaving him alone?

Lance is now a county commissioner. He was elected to the three-person commission in 2012. Yep, Lance is the developer of more than half the land in the county, he owns the county’s only brothel, and he is one of three men leading Storey County government.

He’s also the guy saying Old Reno should be leveraged, not vanquished.

The sagebrush, the wild horses, the brothels, all that Nevada stuff—all that Old Reno stuff—it’s what visionary tech CEOs want, he says. The Old Reno ethos appeals to the guys who buck the norm and take big chances. Guys like Elon Musk.

Gilman’s lawyer Kris Thompson underscores the point.

Kris Thompson: I mean, these guys are rogues. They like this environment here. So leverage it. Don't feel shame for it.

Anjeanette Damon: On our drive through the industrial park with Lance and Kris, we took a spin through the Gigafactory parking lot so they could show us what their leveraging of Old Reno’s culture has accomplished.

Kris Thompson: Look at all the cars. This is all payroll. It's all jobs. It's all service contracts. None of this is visitors. This is all payroll. It's like a college football game. I mean, you can feel the economic power of payroll just by looking at all the cars here.

Anjeanette Damon: It’s true, Tesla and its partner Panasonic have brought a lot of jobs to Reno. I see these factory workers’ vehicles all over town at grocery stores, gyms, even the Ponderosa Hotel parking lot. Their telltale black and white parking passes give them away.

Tesla execs from Silicon Valley fill the lobbies of Reno hotels. Japanese Panasonic workers take buses from downtown to the Gigafactory—a daily pilgrimage that John, the guy fighting to save his home at the Ponderosa, can see from his window.

Because of the state’s tax abatement deal, the city is losing out on tens of millions of tax dollars in exchange for those jobs. Yet it’s also bearing the brunt of the company’s impact: scarce housing and spiking costs. Tesla workers are living in RVs on the street and homeless tent villages are proliferating on the river.

It all feels so tenuous, too. Like a silver mine that could go bust at any moment, leaving Reno in the dust.

Since 2015, Tesla has posted just four profitable quarters.

At dinner parties in Reno, Tesla executives joke that the company could be one tweet away from imploding—Elon Musk was fined $20 million by the SEC because of a tweet he sent last year.

Tesla’s CEO is impulsive. He makes grandiose promises that his employees are on the hook to fulfill. He’s running this grand experiment to save the world from an unsustainable path and he demands work at breakneck speed. The workers in Reno are living that experiment.

All of this makes me want to see what’s going on behind those massive concrete walls at the Gigafactory.

Caller: Yes, we have a head injury here at the Tesla Gigafactory. We just got a call that he was struck in the head by an object that came off the roof.

Robin Amer: That’s after the break

ACT 2

Robin Amer: Much like Tesla’s shiny electric cars, its tech jobs are sought-after status symbols, not just in Reno, but for cities around the country. But when you look behind this sales pitch, the reality of those jobs is a bit more complicated.

Here’s Anjeanette.

Anjeanette Damon: Getting inside the Gigafactory is not an easy proposition.

Elon Musk is notoriously secretive, constantly guarding himself against what he describes as his enemies: The oil industry, the legacy car industry, Wall Street short sellers. He even bought up thousands of acres of land around the Gigafactory to prevent looky-loos from getting a glimpse of what might one day be the largest building in the world.

But after a couple months of talking with Tesla’s press people, I finally wore them down.

Field producer Fil Corbitt and I are standing in a cavernous concrete hallway that more resembles a freeway. Our Tesla handlers are hovering. During this tour, they’re never more than an arm’s length away.

Forklifts loaded with trays of hundreds of battery cells are screaming past us. Some have forklifts drivers, others are autonomous vehicles, using cameras and sensors to guide the hulking crafts. I find myself thinking maybe those are the real jobs of the future.

The Gigafactory is as tall as a seven-story apartment building, but it’s more than half a mile long and nearly a quarter mile wide at its widest point. Our tour guide, an executive named Chris Lister, says he walks 20,000 steps a day. That’s 10 miles for those of you not already obsessed with your pedometer.

Fil Corbitt: Have you ever gotten lost in here?

Chris Lister: Lost? Oh yeah, definitely.

Anjeanette Damon: Before he can even finish his thought, it happens to us.

Chris Lister: ...and certainly in this environment … I think we just walked down the wrong... Speaking of getting lost...

Anjeanette Damon: The human workforce here is diverse and casually dressed—young, tattooed men and women in flannel and jeans along with older, burlier colleagues.

They work side by side with giant robots that swing heavy battery packs through the air and smaller robots that do things like pluck up battery cells and deposit them in testing trays.

This first Gigafactory is almost like a test kitchen for Tesla.

Chris Lister: The thing about the Gigafactory 1 is, it was really an experiment in, how can we make things as efficient as possible? And you know, Gigafactory 10, let's say, is gonna be ten times better than Gigafactory 1 from all of the learnings that we capture as we go on.

Anjeanette Damon: Ten Gigafactories? That seems insane. Particularly when you realize that the goal for this one building is to essentially double the world’s current output of battery cells.

But this whole experimentation thing has contributed to the chaotic atmosphere at the Gigafactory. They’re building systems and manufacturing lines and designing processes at the same time they’re trying to meet these lofty production goals.

Some areas are about what you might expect from a futuristic factory: clean and orderly. In other areas, the floor is cluttered with cardboard and cables and other junk. The whole place feels overwhelming.

So, I’m not the only journalist looking into Tesla. And I knew from other reporting—for instance, the work by the podcast Reveal—that Tesla’s factory in Fremont, California, had a troubling safety record. And other media had reported on dangerous situations out here at the Gigafactory.

So, I went on a public records hunt, gathering from as many different sources as I could: 911 calls, OSHA workplace safety reports, ambulance records. And I was able to piece together kind of a mosaic of safety problems at the factory.

It’s hard to get an accurate accounting of workplace injuries for reasons I’ll get into a little later. But what I did find proves this work can carry a human toll. Different perhaps from Old Reno jobs like stripping, but painful nonetheless.

In the first three years the Gigafactory was open, state OSHA inspectors visited 92 times because of complaints or injuries. Other businesses in the industrial park were visited by inspectors an average of one and a half times in that same period.

I also asked Storey County for a list of all of the 911 calls from the Gigafactory since construction began in 2015. They came back with an index of nearly 1,300 calls.

Some of them are pretty disturbing. Like this one from June 2018.

Caller: We need an ambulance. We have a female employee that her, she got a hand stuck between the two modules, and she's bleeding pretty bad. We have the EMT working on it right now.

Anjeanette Damon: It’s not surprising that the Gigafactory generates more 911 calls than any other location in the county. It’s a small county and the factory is a huge employer. But remember, Tesla is paying very little in taxes to support that kind of service.

In 2018, someone called 911 from the Gigafactory more than once a day, on average for things like fights, suicide attempts, DUIs, theft, drug overdoses.

A quarter of those 911 calls, excluding the hang ups, were for medical problems—heart problems, difficulty breathing, seizures, pregnancy issues—and workplace injuries. Like this one from January 2018.

Officer Fritz: This is Officer Fritz with the Tesla security department, 1 Electric Avenue. We are requesting EMS for a middle-aged male. He was electrocuted, um.

Dispatch: OK, and he is no longer being electrocuted at this time, correct?

Officer Fritz: Correct.

Anjeanette Damon: That guy who was electrocuted, he didn’t want to talk to me. But his union rep says he’s doing OK now.

This next call came in during a windstorm in February 2017.

Caller: We have a head injury here at the Tesla Gigafactory. We just got a call that he was struck in the head by an object that came off the roof.

Anjeanette Damon: A minute later, while security is still on the phone with dispatch, another person is injured. This guy was knocked unconscious by a flying piece of plywood after he stepped out of the bathroom.

Caller: We're getting another call. We have a second injury.

Dispatch: Oh, do you? OK. A different person?

Caller: Yes.

Anjeanette Damon: Whoever had been working on the roof the day before hadn’t secured a bunch of construction material and it all came flying off when the 65-mile-per-hour wind hit. In total, three people were injured.

What really struck me listening to all of these 911 calls was the sheer confusion during emergencies.

Someone gets hurt deep inside the factory. Then, a worker will radio to a guard in a far away security shack. That security guard calls 911, but then can’t answer the questions posed by the dispatcher—questions that need answering in order to get the person help. Unreliable radio communications at the Gigafactory make that problem even worse.

You can hear it in this call from September 2017:

Caller: Yes, this is Officer Fritz with Tesla security. We are located at 1 Electric Avenue. We are requesting EMS.

Dispatch: OK, what's the problem?

Caller: Um, we're still awaiting what the issue is. We were just told to call EMS.

Dispatch: OK, well, I need some kind of a nature of the call, like a....

Caller: Alright, I'm gonna try to get him back on the radio. We're having really bad radio communications with them right now.

Anjeanette Damon: When a big incident occurs, it can be downright chaos.

This is from a chemical spill in April 2017.

Dispatch: Storey County Communications, this is Rachel.

Caller: Hi, Rachel. Yeah, I'm just calling to report a chemical spill in our Module A, first floor. We have evacuated this floor, this area. Requesting the fire department to respond. Apparently it is an inhalation issue.

Dispatch: OK, what was the chemical?

Caller: Um, I do not have it with me

Anjeanette Damon: This is unusual.

Generally in manufacturing settings, the company knows what chemicals it’s working with and can relay that information to dispatch quickly. Federal law mandates that companies keep safety sheets that detail chemicals and their hazards. Tesla did have these sheets on site, but the guy calling 911 didn’t have immediate access to the information.

Turns out that someone had knocked over a 55-gallon drum full of carbonic acid—a flammable chemical that can irritate the skin, eyes, and lungs.

The dispatcher tells the Tesla guy he needs to evacuate everyone.

Dispatch: OK, you need to get everyone out of the building.

Anjeanette Damon: Wait, the entire building? Remember, this is early 2017. Only about 800 people work at the Gigafactory at this point. But it’s still a huge building. The enormity of this task seems to dawn on the Tesla guy.

Caller: Out of the entire building or the floor?

Dispatch: I would, I would get everyone out of the entire building for now.

Caller: OK. Thank you.

Anjeanette Damon: But Tesla doesn’t seem prepared for or willing to do this. According to the incident report, firefighters found complete disorder when they arrived and they got, quote, “resistance” from Tesla representatives.

Firefighters set up a decontamination area, roping off the danger zones. Workers ignored them. No one could provide a list of evacuated employees either. In all, 21 people needed treatment for burning eyes and skin, difficulty breathing, nausea and dizziness. Twelve went to the hospital. After an investigation, OSHA concluded that no workplace safety rules were violated.

I met up with a former Gigafactory manager who presided over a similar incident that happened more than a year later, in 2018.

Chad Dehne, a former Marine, was hired by an agency to manage a crew of temporary workers inspecting battery canisters for defects.

He devised his own check-in sheet to keep track of who was working on his team on any given day, because new hires were constantly appearing.

Chad Dehne: It was a good thing my Marine Corps training came in again, because a lot of times, we didn't know exactly who was in the building.

Anjeanette Damon: That check-in sheet came in handy during one shift when Chad says some guys ran into the room yelling at everyone to evacuate the building and his crew scattered in four different directions.

No one had trained them on how or where to evacuate, so Chad set about tracking down his own people.

Chad Dehne: Boom. Come to find out there was two people that were still inside the building. I went inside the building, they were in there working! And being exposed! These guys said, “Evacuate the building,” and just beat feet. And not one person was responsible for going in there to make sure that everybody was gone.

Anjeanette Damon: This is what troubles Chad the most. Things were happening so fast and production goals were so intense, that it didn't seem like Tesla was fully focused on keeping people safe.

Lane Dillon knew work at the Gigafactory wouldn’t be easy.

Lane is a down-to-earth guy in his early 20s. I met with him out at his family’s home on the bank of the Carson River east of Reno last year.

Lane Dillon: Do you want anything to drink? Yeah, like water? Milk? Beer?

Anjeanette Damon: Milk. I just love that he offered us milk. Lane was an Eagle Scout, vice president of his college Physics Club, and the day I met him he had just been accepted into grad school.

Lane: So I did a undergrad in physics and then today I just got news. I found out I got accepted to Georgia Tech to do aerospace engineering for a masters degree. [Laughs]

Anjeanette Damon: Congratulations! Oh, that’s so exciting!

Anjeanette Damon: In July 2017, he was home from college and needed a summer job. The Gigafactory was ramping up hiring. So he decided to apply.

Anjeanette Damon: In your mind, what was Tesla like before you started working there?

Lane Dillon: The next best thing. It still is.

Anjeanette Damon: Lane was hired through a temp agency that supplied workers to the Gigafactory.

His job was assembling and installing battery racks—these huge, heavy, metal racks that hold trays of battery cells and are anchored to the factory floor.

Lane wasn’t a stranger to manual labor. He ran his own firewood chopping business. But his first week on the job, he was already starting to feel nervous.

He said other temp workers had been getting hurt.

Lane Dillon: And I can specifically remember waking up that morning and thinking, “Man, I hope nothing happens to me.” [Laughs]

Anjeanette Damon: That day, he was helping his crew install a battery rack. His job was to line up the rack with anchor bolts on the ground as a team of people held it up. He was still positioning the rack when the crew let go of it. He couldn’t get his hand out fast enough.

He had gloves on, so he couldn’t see what damage was done at first. When he finally got a look at it, he saw the top inch of his right pointer finger had been smashed off.

Lane Dillon: As soon as I got to the trailer, I said, “I want some ice right now because I want to put my finger back on.”

Anjeanette Damon: But his finger was too damaged to reattach. Lane spent the night in the hospital. Had surgery the next day. It took the rest of the summer to recuperate before he went back to college.

Lane isn’t the only person to hurt a hand at the Gigafactory. In the 911 calls and OSHA documents I reviewed, I found seven reports of serious hand injuries. Like the guy who lost a finger in a wire cutter that didn’t have a proper safety guard. And the day that two workers had their hands crushed by the same piece of equipment in separate incidents just hours apart.

But none of the 911 calls we sifted through were for Lane’s injury. In fact, no one ever called 911 for Lane. His foreman just drove him to the urgent care clinic.

Lane’s actually an example of why it’s so difficult to get an accurate accounting of workplace injuries at Tesla. There’s no public record of his amputation. OSHA could find no record that his injury had ever been reported to them, even though by law it should have been.

Tesla refused to let me interview anyone from the company about any of these safety issues—the high number of 911 calls, the injuries, the confusion during emergency response. Instead, they provided a statement accusing my news organization of being unfair for focusing on safety.

I’m quoting from it here:

“USA TODAY’s reporting presents an inaccurate view of Tesla’s safety record by targeting a few isolated incidents that are not representative of our overall safety culture at Gigafactory 1. Tesla, our suppliers, and our contractors make up over 10,000 people on-site—the size of a small city. To report that both personal and work-related medical emergencies over the course of four years make Tesla an outlier is unfair and misleading.”

Tesla also claimed that the Nevada Gigafactory has a better safety record than the industry average, but it declined to provide any data to help us verify that claim.

Lane isn’t mad at Tesla, not exactly. He tells me he wishes it were a safer place to work, but still thinks what the company is trying to accomplish is worthwhile. When he sees a Tesla on the street, he says he kind of grinds his teeth. But he still wants to own one someday.

Lane Dillon: I understand what Tesla's doing is really hard. And there's gonna be bumps along the way.

Anjeanette Damon: Lane’s sentiment—that there will be bumps along the way, but they’re to be expected—is shared by a lot of people in Reno.

Despite the injuries, despite the overloaded emergency response system in Storey County, despite the housing crunch and the traffic jams, few people say landing Tesla was a bad move.

And it’s true that Tesla has opened up opportunities to some who had few options in the Old Reno economy.

Take Isabelle West, for instance. She’s an endearing 19-year-old with bright pink hair. She grew up in Las Vegas, struggled through high school and couldn’t get into college.

But through a program for at-risk students at her school. She got an interview with Tesla.

Isabelle West: And it took two weeks, but that phone call, my mom was right there with me. And I was just like smiling and she was like smiling at me. And then once my smile came up a little bit bigger she was jumping up and down. Then, like my mom and me, we, like, called up my dad and were like, “She got the job!”

Anjeanette Damon: She works at the factory assembling battery packs. Her starting pay was $14.50 an hour—double Nevada’s current minimum wage. Isabelle says her job can be tedious and stressful at times. But she says co-workers look out for each other. And she’s training at the local community college to become a technician—education that Tesla is paying for.

Isabelle West: Now that I'm actually, like, seeing it firsthand, I’m like, yeah, this is me. This is what I really like. And Tesla kind of helped me figure out myself. When boosters talk about New Reno as a bustling, tech-based, manufacturing economy, Isabelle’s journey is exactly what they’re envisioning. The safety issues, the injuries like Lane’s, to some extent they’re part of the deal, according to Mike Kamierski.

Mike Kazmierski: You know, people haven't figured out what's the safest way to do things, and I think because it is a technology company trying to change the world, it's reinventing that processes. There is room for error there. The risk is totally worth it, he says.

Mike Kazmierski: Well, I mean, I go back to where were we eight years ago? Without advanced manufacturing, we were a community dying. Now we're a community on the rise, because advanced manufacturing brings in quality jobs with risk and it brings in technology. Still, that logic suggests that in the rush to embrace change, some people have to lose for others to win. To Chad Dehne, the former Gigafactory supervisor, that is not the only option.

Chad Dehne: I know that they provide jobs for a lot of beautiful families here in the Reno area and beyond. But at the same time, with that being said, there's a protocol that you've got to follow so that those people can go home safe and sound to their families or not or not suffer ill effects from things they may have been exposed to down the line.

Robin Amer: Tesla brought a lot of jobs to Reno’s economy. Jobs with a career path and a livable wage. But high tech isn’t always the silver bullet that cities want it to be and reinventing the economy comes at a price, whether it’s injured workers, or people like Velma and John, pushed to the brink of homelessness. Or people like Stephanie, now at risk of losing her livelihood. In the race to land that big economic development win, it seems no one is really looking out for the little guy. But that doesn’t mean that the status quo is OK. For example: Kamy has always insisted that the claims about his strip clubs are bogus. But next time on The City, we pull back the curtain on Kamy’s strip club empire to reveal what’s really going on.

Kamy Keshmiri: The reason why I have no citations is because I run these clubs ultra clean … There's a reason why we have a perfect record.

Tawny: They are fucking liars. They're liars.

Robin Amer: That’s next time on The City.

CREDITS

The City is a production of USA TODAY and is distributed in partnership with Wondery. You can subscribe to the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you’re listening right now. If you like the show, please rate and review us, and be sure to tell your friends about us. Our show was reported and produced by Anjeanette Damon, Fil Corbitt, Kameel Stanley, Taylor Maycan, and me, Robin Amer. Our editors are Amy Pyle and Matt Doig. Ben Austen is our story consultant. Original music and mixing is by Hannis Brown. Legal review by Tom Curley. Launch oversight by Shannon Green. Additional production by Emily Liu, Sam Greenspan, Wilson Sayre, and Jenny Casas. Brian Duggan is the Reno Gazette Journal’s executive editor. Chris Davis is the USA Today Network’s VP for investigations. Scott Stein is our VP of product. Maribel Wadsworth is our president and publisher. Special thanks to Liz Nelson, Kelly Scott, Alicia Barber and Alan Deutschman. I’m Robin Amer. You can find us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram @ thecitypod. Or visit our website. That’s thecitypodcast.com

In Episode 4, we leave Reno and head east…

…towards the sprawling Tahoe-Reno Industrial Center (TRIC). Here, companies like Tesla are buying up land to build mega-factories and warehouses, sparking the changes at the heart of Reno’s strip club fight.

_________

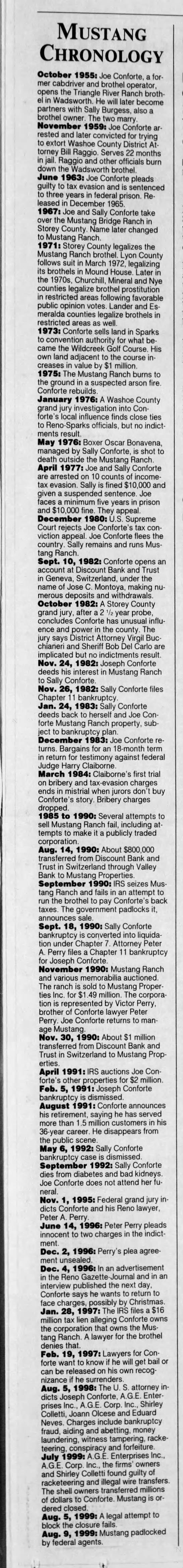

But first, a pit stop at The World Famous Mustang Ranch

A legal brothel with a colorful history on the outskirts of TRIC. In 1999, the federal government seized the brothel and shut it down.

_________

_________

The events leading up to this moment read like a Hollywood script…

The murder of an Argentinian boxer. A federal indictment. Arson and extortion. A con man fleeing the country to South America.

_________

_________

Enter developer Lance Gilman

Losing the brothel put Storey County in a tough spot. In 1998, Gilman and his partners bought more than 100,000 acres of land there. They had big plans for it. So to keep his vision—and the county—alive, he buys the Mustang Ranch, too.

_________

_________

A ‘labor of love’

In 2019, Gilman told us, “I don’t think there is a business in America that would generate cash flow instantly except the brothel business.” But the Great Recession was hard on Nevada—even the brothels.

During this time, Gilman used novelty events—like the ‘Hunt a Ho’ paintball game mentioned in the episode—to bring in extra cash. The game was documented in this pilot for a reality TV series about Gilman, his then-wife Susan and their experiences running the brothel together.

________

_________

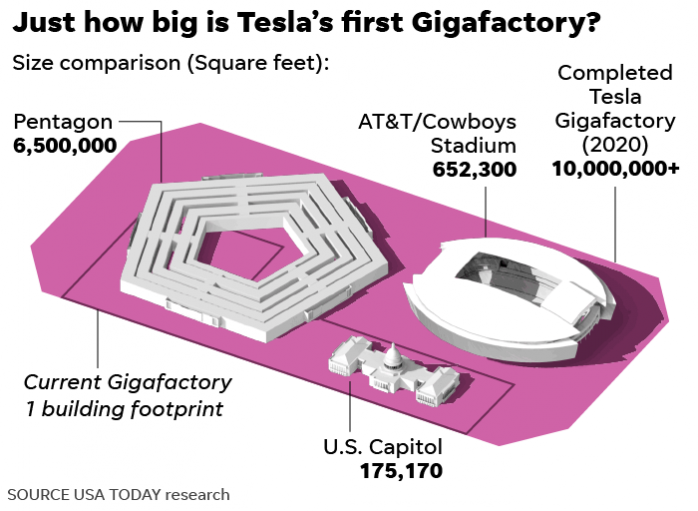

Our next stop: The Tesla Gigafactory

Tesla is building its Gigafactory on the land Lance Gilman bought back in the 1990s. It could one day be the world’s largest building.

_________

_________

Our final stop: Inside the Gigafactory

By Benjamin Spillman, Reno Gazette Journal (published December 10, 2018)

Big numbers are one way to appreciate Tesla’s gargantuan Gigafactory.

Operating 24-hours a day, workers produce enough battery packs and drive units in a week to power 5,300 of Tesla’s Model 3 sedans. Tesla says that at 5.4 million square feet, roughly equivalent to 50 Home Depot stores, the factory is just 30 percent of its potential size and is already producing more batteries than all other carmakers combined.

With more than 7,000 workers, the factory is responsible for increasing manufacturing employment in the Reno-Sparks area by 55 percent since 2014, according to the Governor’s Office of Economic Development.

In December 2018, we got a rare glimpse inside the factory. Click here to finish the tour at the Reno Gazette Journal.

Transcript

Robin Amer: Hey everyone. Just a reminder that because this season of The City is about strip clubs, it won’t be suitable for everyone, especially kids. This episode contains explicit language, including explicit conversations about sex.

Production team member: Previously on The City…

Mayor Hillary Schieve: We are truly rebranding this city, and companies like Tesla, Amazon, and Apple are all building and investing right here.

John: I’ve seen the entire crew marching every morning out of Harrah’s and out of Circus, marching over getting on the shuttles to get bussed out to the Gigafactories. Tesla, Panasonic, so on.

Bryan McArdle: As you drive through Midtown, you see all this vibrancy—these new restaurants, new small businesses popping up, and that specific strip, it just stands out. It’s, like, such a sore thumb.

Robin Amer: If you drive east from Reno about 20 miles, you leave the city behind and you find yourself in this incredible landscape, where this river canyon flows between these sagebrush-covered mountains and eventually you’ll get to the spot where the desert floor opens up a bit and those beautiful mountains give way to massive warehouses and factories.

From above, the buildings look like these big white tetris pieces just scattered among the rolling hills. Hills that have been carved up to make space for all this new construction. This is the Tahoe Reno Industrial Center and in this unlikely landscape New Reno is springing to life.

It’s where Tesla CEO Elon Musk built a giant battery factory, the Gigafactory, which churns out millions of battery cells a day. The same battery cells that power his famous electric cars.

Now, the 2014 arrival of the Gigafactory was a game-changer for Reno’s economy, bringing with it 7,000 jobs. And last fall, the state hosted a summit to celebrate that accomplishment.

Outgoing Governor Brian Sandoval sits on stage, in front of an audience of boosters and fellow lawmakers and the press, and paints a bleak picture of his state’s economy before Tesla’s arrival.

Brian Sandoval: And it was October of 2010. The unemployment rate was 14.3 percent. Nevada led the nation in bankruptcies. We led the nation in foreclosures. In October, exactly eight years ago, there was a front-page story in the Reno Gazette Journal above the fold that said “Reno: Detroit of the West.”

Robin Amer: Now though, he’s beaming with pride. Companies like Apple and Amazon have opened in the state. But none represent the New Nevada better than Tesla.

Elon Musk is on stage too, sitting next to Sandoval. Musk is wearing a charcoal suit coat, no tie, and slim-fit jeans—you know, the uniform of Silicon Valley CEOs. Sandoval launches into some friendly chit chat.

Brian Sandoval: So when you came over that hill over here and and you see this, this landscape, did you look at it and say, this is the place?

Elon Musk: Yeah. [Laughs] This is beautiful. You know, there’s like ten thousand wild horses here? I mean, this really looks like something out of a, it’s like the idyllic Wild West. It’s incredible.

Robin Amer: But it wasn’t just the wild horses that drew Musk here. Something much more fundamental—something much more Old Reno—influenced his decision.

Elon Musk: You know, I think this is very much the land of opportunity here. Like, feels like freedom, right here. Feels like freedom, OK? That’s good.

Robin Amer: Freedom. The same freedom that fueled Old Reno’s vice-based economy of quick divorces and legal gambling, well, it’s attractive to corporate America, too. No income taxes. Lightning fast project approvals.

But when a giant corporation can come to town and build a mega factory at a breakneck pace, things can go wrong. And just as the dancers working in Old Reno’s strip clubs face difficult working conditions, so too do the workers in New Reno’s factories.

Officer Fritz: Yes, this is Officer Fritz with the Tesla security department, 1 Electric Avenue. We are requesting EMS for a middle-aged male. He was electrocuted.

Caller: We need an ambulance. We have a female employee that her, she got her hand stuck between two modules and she’s bleeding pretty bad.

Robin Amer: Tesla’s Gigafactory helped jumpstart Reno’s economy, but it came at a cost. One that New Reno boosters working hard to kick strip clubs out of downtown don’t like talking about. One that leaders who scrambled to bring Tesla here didn’t really plan for or address. One that might make you wonder whether the New Reno is really all that different or even that much better than the Old Reno.

From USA TODAY, I’m Robin Amer and this is The City.

ACT 1

Robin Amer: When Elon Musk went looking for a place to build his battery factory, he was under tremendous pressure. He had promised the world the mass production of the Model 3, an all-electric sedan that was supposed to be somewhat more affordable than the luxury sports cars his company had been making.

He needed a factory fast. So he needed a place where he could build it with as little red tape as possible. And a guy named Lance Gilman had just the spot.

Here’s our reporter, Anjeanette Damon.

Anjeanette Damon: Lance Gilman is the kinda guy who is always wheeling and dealing. Like the afternoon I went to meet him at the Tahoe-Reno Industrial Center he was a few minutes late.

Lance Gilman: I hope we didn’t keep you waiting too long.

Anjeanette Damon: No, not at all.

Lance Gilman: We’re sitting over in another meeting and it was spirited. So we ran close, so—

Anjeanette Damon: Uh oh!

Lance Gilman: It’s fine, it worked out really well. It had a lot of energy attached.

Anjeanette Damon: Lance looks right at home in this setting, wearing a cowboy hat and bolo tie. It’s a uniform he’s adopted since moving from Southern California to Reno in the 1980s, trading the expensive tailored suits from his days as a music promoter for western garb.

Lance and his partners bought this land in 1998—more than 100,000 acres worth. That’s about seven-and-a-half times the size of Manhattan.

Today, he’s here to take me on a quick driving tour of the park.

When he and his partners bought this land, it was nothing but dirt roads and sagebrush. The corporation that owned it was actually thinking of turning it into a big game hunting park.

Lance Gilman: We had to build 300 lane-miles of road. So we put in all of the sewer, all the water, all the gas, all the fiber.

Anjeanette Damon: As we’re driving, we come across this road crew. They’ve stopped work while a guy with a bright orange sign shoos a tarantula the size of a man’s hand out of the worksite.

Lance Gillman: There’s tarantulas out here. There’s scorpions, there’s tarantulas, there’s rattlesnakes. This is Nevada desert! [Laughs] And it’s all here.

Anjeanette Damon: Lance drives us up a steep dirt road to a flat knoll. From this vantage point, you can see the park’s sweeping landscape.

Lance Gillman: So we can step out here and we’ll look out here.

Anjeanette Damon: He starts pointing out the park’s tenants.

Lance Gillman: So that’s the Tesla building across over there to the right with the red stripe. That’s a five thousand acres. The big building right below us, the largest one, is Zulily.

Anjeanette Damon: Zulily is an online clothing retailer. Its building is about five times larger than your typical Costco.

Lance Gillman: And then the guys just below us is U.S. Ordnance. Fifty-caliber machine guns. They’re sitting on about $50 million worth of machine gun orders to Saudi Arabia right now. It’s amazing.

Anjeanette Damon: Diapers.com, Walmart, Ebay, Petsmart. They all have giant buildings out here.

And a steady stream of semi-trucks rolls through the park, pulling into the warehouse loading docks to drop off and pick up the online purchases of millions of Americans. You know that big screen TV you ordered from the comfort of your couch after drinking a little too much wine? Or the cute shoes you bought on impulse? Or the flowers you sent your mom? They may have come through one of these warehouses.

As we’re talking, a band of wild horses wanders by, frolicking in the dirt, munching on the scrub brush.

Lance Gillman: We have about a thousand head of wild horses. The companies that are out here love them. Elon Musk has them on his Web site.

Anjeanette Damon: Yeah, Elon loves them, but many native Nevadans—ranchers especially—have more of a love-hate relationship with the wild horses. In real life, they aren’t just a living prop in a Wild West theme park. They can overgraze the land, muddy water sources.

But it’s not just the wild horses that really drew the CEOs here. The selling point is the lack of government bureaucracy—the same permissiveness that in the past encouraged the capitalization on vice. Now it’s the cornerstone of Silicon Valley’s expansion into Northern Nevada.

We head back to a small county office building in the middle of the industrial park. Inside is a tiny office.

Lance Gilman: We’ve done a lot of major real estate deals right here.

Anjeanette Damon: Yeah? Who’s sat in this room? Any names we would recognize?

Lance Gilman: Oh sure. Tesla and Google and pretty much, Blockchains. Pretty much everybody.

Anjeanette Damon: A conference table takes up most of the space. This is where Lance helped land the Gigafactory deal.

Back in 2014, states across the country were trying to woo Tesla with huge tax incentives. It was all part of a familiar dance, states and cities launching elaborate campaigns to attract big tech companies with tax incentives and land deals. In other places, those enticements have sparked their own backlash, like when New Yorkers rose up to scuttle a $3 billion deal to bring in an Amazon headquarters.

Anjeanette Damon: But five years ago in this little room, Lance wanted to know why Tesla hadn’t yet picked a place for its Gigafactory.

Lance Gilman: Texas was offering them billions of dollars to come to Texas. And New Mexico was in the hunt. And Arizona was in the hunt. And California was offering them billions of dollars to come to California.

Anjeanette Damon: Two Tesla higher-ups scouting locations told Lance they couldn’t afford any delays in the building schedule—no pesky zoning fights, no labor-intensive environmental assessments, no lengthy permitting times.

They asked him:

Lance Gilman: Well, how fast could we get a grading permit?

Anjeanette Damon: A grading permit. It’s kind of a boring piece of paper, but it will let them start clearing the land, getting it ready for construction. Tesla needed to move the equivalent of 42 Olympic swimming pools worth of dirt before building could start.

The county’s planning manager, Dean Haymore, was sitting next to Lance in this meeting.

Lance Gilman: So Dean took a piece of paper out of his notebook and he said, “That’s your grading permit. Fill in your name and you can leave here with it.”

Anjeanette Damon: Handing Tesla execs a permit scrawled on a torn sheet of paper was a symbolic move. But here in Storey County, things move almost that quickly. On average, it takes less than seven days to get a grading permit, less than 30 days to get a building permit. In many cities, it can take months, even years, to get that first permit.

Lance Gilman: Three and a half weeks later, the grading on probably one of the largest pads ever done in the United States—three and a half weeks!—I stood on a bank watching this anthill of activity going on with Yates Construction, their vice president, and he said, “Lance Gilman, this could have only happened maybe one other the place in the world today. That would’ve been China.”

Anjeanette Damon: Nevada: the China of the West, I guess.

But how could they possibly move that fast? In short, Lance and his partners did all the bureaucratic work up front years ago, clearing the way of any zoning hurdles way ahead of time so companies don’t have to come to town and argue for months before a planning commission.

Lance Gilman: What we did out here is not just zoning. We pre-approved every industrial project in the United States known at the time. It was all pre-approved. So if you were doing batteries, you were pre-approved. If you were doing flowers, you were pre-approved. If you were doing tires, you were pre-approved.

Anjeanette Damon: Want to build a giant battery factory? Get it up and running within a year? Pre-approved.

A few months after Tesla cleared the land for its factory, Nevada lawmakers took just two days to approve the tax abatements that sealed the deal with the company. It was the largest tax incentive package in state history.

Lawmakers were easily swayed by Tesla’s promise: the company would build its Gigafactory in Nevada, create thousands of jobs, invest millions of dollars in construction, and, in return, it would pay virtually no taxes for 20 years. In their rush though, lawmakers didn’t do any traffic studies or environmental studies or make sure the region had enough housing for all those new workers.

Even Musk pleaded for more housing at the governor’s tech summit.

Elon Musk: My biggest constraint on growth here is housing and infrastructure. [00:38:30] I think we’re gonna, we’re looking at creating a sort of housing compound just on the site of the Gigafactory, using high quality kind of mobile homes, which I think would be great because then people could actually just walk here.

Anjeanette Damon: Lance Gilman played a starring role in an ensemble cast of people who brought Tesla to Nevada. Another actor on that stage was Mike Kazmierski, the buttoned up former military commander who heads Reno’s economic development arm—the anti-strip club guy.

You might think these two gentlemen, Mike Kazmierski and Lance Gilman, would be allies joined by the common goal of remaking Reno’s economy.I asked Mike Kazmierski about it when I interviewed him last spring.

Mike Kazmierski: Uh, Lance Gilman is two people.

Anjeanette Damon: On the one hand, Mike says Lance is a gifted salesman—the pitch-perfect spokesman for the Wild West industrial park that nabbed the Gigafactory. On the other hand?

Mike Kazmierski: Lance Gilman is a brothel owner, um, has been called a pimp.

Anjeanette Damon: Lance squirms, even gets down right mad, if you call him a pimp. A pimp, in his view, is a criminal.

But Lance does own a legal brothel—the Mustang Ranch, one of the most famous in the country. And it’s right on the outskirts of his industrial park.

Unlike Mike, Lance doesn’t see anything wrong with the two co-existing.

Lance Gilman: Mike Kazmirski, God love him, is not a Nevadan. [00:10:15] He’s not into the Nevada culture. And so if you really drill down into where Mike lives, in his world, he doesn’t like online gaming. He doesn’t like strip clubs. He doesn’t like brothels. Mike would completely change our Nevada culture if he could.

Anjeanette Damon: In some ways, Lance Gilman has managed to straddle that divide between people like Mike Kazmierski and Reno strip club owner Kamy Keshmiri. He’s maintained Old Reno-style vice as a brothel owner, and he’s the guy who helped land Tesla, New Reno’s biggest win.

It raises another question: If Lance Gilman can bridge both worlds, why can’t they?

Contrary to popular belief, brothels aren’t legal in Reno, or even Las Vegas. But they are legal in many of the smaller counties on the outskirts of town.

Lance’s brothel is on the edge of the industrial park, but you’d never know it. It’s tucked into a quiet hillside, surrounded by big cottonwood trees. It’s just 15 miles from downtown Reno.

Unlike Mike Kazmierski, who’s repelled by Nevada’s smutty reputation, Lance Gilman relishes his role as a brothel owner. He holds business meetings at the brothel from his large round table in the corner of the lavish front room—the same room where women pair up with their customers before leading them into the back for another kind of business encounter.

This place is so integral to who Lance is and how he capitalizes on both the Old Reno and New Reno worlds, that I wanted to see it.

Lance Gilman: Good morning! Or afternoon I guess now.

Anjeanette Damon: When you first walk into the brothel, you’re actually entering the Wild Horse Saloon, a seemingly regular old restaurant and bar.

The lights are low, small tables dot the floor, and there’s a bar against the back wall. You can come here just for a beer and a burger if you want.

There’s a stripper pole in the corner. But unlike in Kamy Keshmiri’s strip clubs, it’s totally OK here to pay for sex in the back.

Anjeanette Damon: I see. You have to go behind the green door.

Lance Gilman: I’m going to take you through the green door.

Anjeanette Damon: OK.

Anjeanette Damon: We walk into what looks like a British hunting lodge: big fire going, lots of taxidermy animal heads on the walls. Lance hands us off to our tour guide, a sex worker named Cherry. She’s petite, with long-flowing brown hair, wearing a silky robe and high heels.

She shows us into a tiny room where ladies and customers come to an agreement on services.

Cherry: We take credit, debit, cash. We’re totally legal.

Anjeanette Damon: Here, women are accepting credit cards for sex, when just 15 miles down the road, Reno City Council members are arguing over whether strippers should be able to perform lap dances.

Before they actually hook up, the ladies inspect their customers for any signs of disease.

Cherry: That is full of baby wipes. This is full of gloves.

Anjeanette Damon: And then it’s off to the fun. You can join a lady in her room—the one she basically lives in during her week-long shift—or spend time in one of the brothel’s more lavish theme rooms. There’s the orgy room, the jacuzzi room, the tropical Hawaii room—even a dungeon.

Cherry: You can really just let your mind run wild. There’s no wrong way to enjoy a dungeon.

Anjeanette Damon: Or, you know, you can just come in for a quickie.

Cherry: I’m not kidding. Some people have, like, they’re ringing our doorbell, like, ding ding ding ding ding ding ding. We’re like, “Go let that guy in. He’s in a rush.” And he’s like, “I have 30 minutes. I’m on my lunch break. It takes me 15 to get to Reno. Are you available?” And you’re like, “OK. Yes. OK, yes.”

Anjeanette Damon: Back in the Reno strip club fight, there’s all this tension between old and new. LIke we can’t have New Reno if we don’t get rid of Old Reno entirely. But this brothel is the epitome of the sordid Old Reno ethos, and it’s alive, even thriving, on the edge of the gleaming industrial park that’s the epitome of New Reno.

In fact, this industrial park, it might never have come to be if hadn’t been for this brothel.

In the late ‘90s, when Lance and his partners were on the hunt for a good spot to develop, they were mainly looking for land.

And Storey County, even though it’s the smallest county in the state, had a lot of it. It was also desperate.

Lance Gilman: They were church mice poor. They were, as a matter of fact, they were on the brink of bankruptcy.

Anjeanette Damon: At the time, the county’s major source of tax revenue was its brothels.

But the Mustang Ranch—the single largest taxpayer in the county—was closing. The previous owner had been indicted on money laundering charges and had fled to Brazil.

The feds shut it down, costing the county about 12 percent of its budget.

The county needed someone to keep the brothel open. Commissioners turned to Lance.

Lance Gilman: I don’t think there is a business in America that would generate cash flow instantly except the brothel business.

Anjeanette Damon: Lance bought the Mustang Ranch from the federal government—on eBay of all places. The county was once again rolling in brothel cash. And so was Lance.

Lance says the brothel generates a million dollars a month in revenue—money he used to help keep the industrial park afloat during the recession. The taxes on that cash also helped Storey County’s government stay afloat.

Lance’s lawyer Kris Thompson puts it this way:

Kris Thompson: And had he not done that, that magic phone call to get that Tesla deal may not have ever come.

Anjeanette Damon: Lance says he prides himself on running a classy joint—the best of the best.

In fact, he says Kamy Keshmiri could learn a thing or two from him.

Lance Gilman: You run the business quietly, out of town. You’re not by a school or a church or any of the public facilities, and you stay below the sagebrush.

Anjeanette Damon: It’s true, the government isn’t all up in Lance Gilman’s business the way the city of Reno is cracking down on Kamy Keshmiri. If the Wild Orchid did a better job of “staying below the sagebrush,” Lance argues, maybe the city wouldn’t be so up in arms.

But things are never that simple. Staying “classy” is not why local government leaves Lance alone. Remember, county commissioners were the ones who asked Lance to re-open the brothel in the first place.

Also, Lance isn’t always so classy himself. Neither are the publicity stunts he uses to promote the brothel. Things like the, quote, “Hunt a Ho” game he concocted, where men chased prostitutes through the hills with paintball guns. Or when he staged a motocross event to try and set a record for, quote, “jumping the most titties in one night.”

Another big reason local government might be leaving him alone?

Lance is now a county commissioner. He was elected to the three-person commission in 2012. Yep, Lance is the developer of more than half the land in the county, he owns the county’s only brothel, and he is one of three men leading Storey County government.

He’s also the guy saying Old Reno should be leveraged, not vanquished.

The sagebrush, the wild horses, the brothels, all that Nevada stuff—all that Old Reno stuff—it’s what visionary tech CEOs want, he says. The Old Reno ethos appeals to the guys who buck the norm and take big chances. Guys like Elon Musk.

Gilman’s lawyer Kris Thompson underscores the point.

Kris Thompson: I mean, these guys are rogues. They like this environment here. So leverage it. Don’t feel shame for it.

Anjeanette Damon: On our drive through the industrial park with Lance and Kris, we took a spin through the Gigafactory parking lot so they could show us what their leveraging of Old Reno’s culture has accomplished.

Kris Thompson: Look at all the cars. This is all payroll. It’s all jobs. It’s all service contracts. None of this is visitors. This is all payroll. It’s like a college football game. I mean, you can feel the economic power of payroll just by looking at all the cars here.

Anjeanette Damon: It’s true, Tesla and its partner Panasonic have brought a lot of jobs to Reno. I see these factory workers’ vehicles all over town at grocery stores, gyms, even the Ponderosa Hotel parking lot. Their telltale black and white parking passes give them away.

Tesla execs from Silicon Valley fill the lobbies of Reno hotels. Japanese Panasonic workers take buses from downtown to the Gigafactory—a daily pilgrimage that John, the guy fighting to save his home at the Ponderosa, can see from his window.

Because of the state’s tax abatement deal, the city is losing out on tens of millions of tax dollars in exchange for those jobs. Yet it’s also bearing the brunt of the company’s impact: scarce housing and spiking costs. Tesla workers are living in RVs on the street and homeless tent villages are proliferating on the river.

It all feels so tenuous, too. Like a silver mine that could go bust at any moment, leaving Reno in the dust.

Since 2015, Tesla has posted just four profitable quarters.

At dinner parties in Reno, Tesla executives joke that the company could be one tweet away from imploding—Elon Musk was fined $20 million by the SEC because of a tweet he sent last year.

Tesla’s CEO is impulsive. He makes grandiose promises that his employees are on the hook to fulfill. He’s running this grand experiment to save the world from an unsustainable path and he demands work at breakneck speed. The workers in Reno are living that experiment.

All of this makes me want to see what’s going on behind those massive concrete walls at the Gigafactory.

Caller: Yes, we have a head injury here at the Tesla Gigafactory. We just got a call that he was struck in the head by an object that came off the roof.

Robin Amer: That’s after the break

ACT 2

Robin Amer: Much like Tesla’s shiny electric cars, its tech jobs are sought-after status symbols, not just in Reno, but for cities around the country. But when you look behind this sales pitch, the reality of those jobs is a bit more complicated.

Here’s Anjeanette.

Anjeanette Damon: Getting inside the Gigafactory is not an easy proposition.

Elon Musk is notoriously secretive, constantly guarding himself against what he describes as his enemies: The oil industry, the legacy car industry, Wall Street short sellers. He even bought up thousands of acres of land around the Gigafactory to prevent looky-loos from getting a glimpse of what might one day be the largest building in the world.

But after a couple months of talking with Tesla’s press people, I finally wore them down.

Field producer Fil Corbitt and I are standing in a cavernous concrete hallway that more resembles a freeway. Our Tesla handlers are hovering. During this tour, they’re never more than an arm’s length away.

Forklifts loaded with trays of hundreds of battery cells are screaming past us. Some have forklifts drivers, others are autonomous vehicles, using cameras and sensors to guide the hulking crafts. I find myself thinking maybe those are the real jobs of the future.

The Gigafactory is as tall as a seven-story apartment building, but it’s more than half a mile long and nearly a quarter mile wide at its widest point. Our tour guide, an executive named Chris Lister, says he walks 20,000 steps a day. That’s 10 miles for those of you not already obsessed with your pedometer.

Fil Corbitt: Have you ever gotten lost in here?

Chris Lister: Lost? Oh yeah, definitely.

Anjeanette Damon: Before he can even finish his thought, it happens to us.

Chris Lister: …and certainly in this environment … I think we just walked down the wrong… Speaking of getting lost…

Anjeanette Damon: The human workforce here is diverse and casually dressed—young, tattooed men and women in flannel and jeans along with older, burlier colleagues.

They work side by side with giant robots that swing heavy battery packs through the air and smaller robots that do things like pluck up battery cells and deposit them in testing trays.

This first Gigafactory is almost like a test kitchen for Tesla.

Chris Lister: The thing about the Gigafactory 1 is, it was really an experiment in, how can we make things as efficient as possible? And you know, Gigafactory 10, let’s say, is gonna be ten times better than Gigafactory 1 from all of the learnings that we capture as we go on.

Anjeanette Damon: Ten Gigafactories? That seems insane. Particularly when you realize that the goal for this one building is to essentially double the world’s current output of battery cells.

But this whole experimentation thing has contributed to the chaotic atmosphere at the Gigafactory. They’re building systems and manufacturing lines and designing processes at the same time they’re trying to meet these lofty production goals.

Some areas are about what you might expect from a futuristic factory: clean and orderly. In other areas, the floor is cluttered with cardboard and cables and other junk. The whole place feels overwhelming.

So, I’m not the only journalist looking into Tesla. And I knew from other reporting—for instance, the work by the podcast Reveal—that Tesla’s factory in Fremont, California, had a troubling safety record. And other media had reported on dangerous situations out here at the Gigafactory.

So, I went on a public records hunt, gathering from as many different sources as I could: 911 calls, OSHA workplace safety reports, ambulance records. And I was able to piece together kind of a mosaic of safety problems at the factory.

It’s hard to get an accurate accounting of workplace injuries for reasons I’ll get into a little later. But what I did find proves this work can carry a human toll. Different perhaps from Old Reno jobs like stripping, but painful nonetheless.

In the first three years the Gigafactory was open, state OSHA inspectors visited 92 times because of complaints or injuries. Other businesses in the industrial park were visited by inspectors an average of one and a half times in that same period.

I also asked Storey County for a list of all of the 911 calls from the Gigafactory since construction began in 2015. They came back with an index of nearly 1,300 calls.

Some of them are pretty disturbing. Like this one from June 2018.

Caller: We need an ambulance. We have a female employee that her, she got a hand stuck between the two modules, and she’s bleeding pretty bad. We have the EMT working on it right now.

Anjeanette Damon: It’s not surprising that the Gigafactory generates more 911 calls than any other location in the county. It’s a small county and the factory is a huge employer. But remember, Tesla is paying very little in taxes to support that kind of service.

In 2018, someone called 911 from the Gigafactory more than once a day, on average for things like fights, suicide attempts, DUIs, theft, drug overdoses.

A quarter of those 911 calls, excluding the hang ups, were for medical problems—heart problems, difficulty breathing, seizures, pregnancy issues—and workplace injuries. Like this one from January 2018.

Officer Fritz: This is Officer Fritz with the Tesla security department, 1 Electric Avenue. We are requesting EMS for a middle-aged male. He was electrocuted, um.

Dispatch: OK, and he is no longer being electrocuted at this time, correct?

Officer Fritz: Correct.

Anjeanette Damon: That guy who was electrocuted, he didn’t want to talk to me. But his union rep says he’s doing OK now.

This next call came in during a windstorm in February 2017.

Caller: We have a head injury here at the Tesla Gigafactory. We just got a call that he was struck in the head by an object that came off the roof.