S1: Episode 1

Six Stories

Chicago, 1990. A guy with a loud sweater, manicured nails and connections to some very powerful people idles in a limousine near a vacant lot. A fleet of dump trucks unloads literal tons of busted concrete—and keep coming back. Neighborhood residents take action. The mess becomes much bigger than a six-story pile of rubble.

Episode | Transcript

Six Stories

Robin Amer: There’s this vacant lot on the West Side of Chicago. It’s about a half-dozen miles from the city’s downtown—what we call the Loop. And this lot is huge.

Robin Amer: This lot looks to me like it's about a full city block. It's a big lot.

Gladys Woodson: Yes, it is.

Jacquelyn Rodney: It's a big lot.

Robin Amer: That’s Gladys Woodson and Jacquelyn Rodney, who live nearby.

Robin Amer: And now it's pretty overgrown. There's full-size trees. There's prairie grass. So what did it look like when he was operating?

Gladys Woodson: It was a mess. It was a mess. That's best I can say for it.

Robin Amer: I first started visiting this lot, which is in a neighborhood called North Lawndale, after hearing a story about that something that happened here.

Gladys Woodson: At first, he had big 18-wheelers lined up. You know, I just thought, "Well, somebody's just parking their trucks in there.” ’Til a guy say, "Ms. Woodson, come down, look at this. Do you know that somebody’s over there dumping in that lot?”

Robin Amer: I’ve been reporting on Chicago for more than a decade and I’ve reported all kinds of stories of the built environment—about secret tunnels hidden underneath the Loop, and about how you replace a train bridge while the train is still running. I’ve also reported on housing discrimination and predatory lending.

So, stories about all of the remarkable stuff that gets built in Chicago. But also about how it gets built—and all the foul and crooked things that people will do when they think nobody’s looking.

And so the story of what happened on this lot—the story I want to tell you—stunned me despite everything I already knew about Chicago. About how corrupt and ruthless it can be. About how stark the divisions are between black and white, rich and poor; between the people who hoard power and the people who will fight for their fair share.

Gladys Woodson: Any time you see anybody drive over in a vacant lot in a limo, you know it's no good.

Robin Amer: This story is about a giant illegal dump. Six stories high.

Jacquelyn Rodney: It was huge mountains...concrete, garbage...

Robin Amer: Built from the broken pieces of a city in the midst of a so-called Renaissance.

Conrad Henry: I thought that downtown, City Hall, would do right by the people. You know, I didn’t think they didn’t care less about us.

Robin Amer: Built not just by dump trucks and bulldozers and construction cranes, but also by corruption, apathy and greed.

Jim Davis: So, I said, "OK, if a public official came by today and said, 'I need $500,' what would you do?" And he reached into his back pocket and pulled out five $100 bills.

Robin Amer: The man who built this dump had deep ties to Chicago’s criminal underworld.

Tony D’Angelo: He looked at the owner of the restaurant, he goes, “If you don't pay your milk money, you're going to get a pineapple through the window.”

Robin Amer: He profited at the neighborhood's expense.

John Christopher: We’re no altar boys at this fucking table. Let’s put it on the table there. I made a lot of money over there.

Robin Amer: And before he was done, the FBI would be protecting him.

I’m Robin Amer. From USA TODAY, this is The City.

ACT 1

Robin Amer: Let’s start at the beginning.

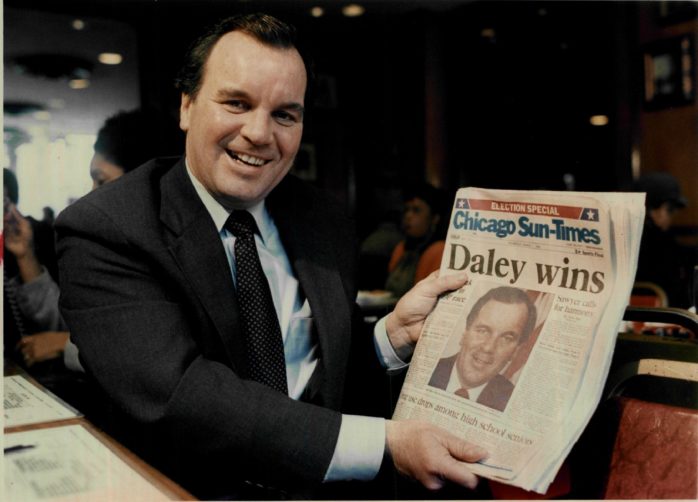

Before the dump trucks came, before the lawsuits and the secret FBI tapes...before the arrests and the president’s executive order...before “the Mountain” appeared and then disappeared, along with the guy who put it there ...there was Daley.

Radio announcer: You're listening to Richard M. Daley deliver his inaugural address live on WBBM AM from Orchestra Hall.

Robin Amer: April 24, 1989. Chicago’s new mayor is sworn into office.

Richard M. Daley: It's time to leave behind old setbacks, disappointments and battles. Because in the campaign for a better Chicago, we're all allies.

Robin Amer: In the 40 years leading up to his inauguration, Chicago had lost nearly a million people, along with hundreds of thousands of jobs. The new Mayor Daley wanted to stem that tide. He wanted his Chicago to wake up from its post-industrial slumber and thrive.

Richard M. Daley: We either rise up as one city or we sit back and watch Chicago decline.

Robin Amer: So Daley began a major push to revamp Chicago’s aging downtown, paying special attention to the tourist-friendly destinations in the Loop and along the lakefront:

He’d go on to renovate Navy Pier—with its 150-foot-tall Ferris wheel.

Expand McCormick Place—the biggest convention center in North America.

And build Millennium Park—with its big silver Bean and Frank Gehry-designed amphitheater.

He also set about rebuilding crucial parts of the city’s infrastructure, including its roads and highways.

Chicago is ringed by highways named for dead politicians: the Kennedy, the Eisenhower, the Stevenson.

Millions of cars and 30 years of wear and tear, and ice and salt had worn down these aging roadways. By the spring of 1990, the city was full of workers in hard hats and orange vests, breaking down concrete, jackhammering asphalt, gathering up dirt, and gravel, loading it into dump trucks and hauling it away.

Law-abiding trucking companies carted this debris to distant landfills. But some trucks headed west. They left behind the skyscrapers of the Loop, and traveled over the Chicago River, into the city’s neighborhoods. They drove through Greektown, and what was left of Little Italy, past the University of Illinois, and the stadium where the Bulls and Blackhawks play, past the county hospital, to a vacant lot in North Lawndale, near the home of Gladys Woodson.

* * *

Gladys Woodson: My first memory was the president of the 4100 Block came down and asked for Ms. Woodson. And I told him, “What do you want with her?”

Robin Amer: Ms. Woodson was the president of the 4300 Block. Together, these block clubs kept eyes on the street, and made sure their community was safe.

Gladys Woodson: He said, “Well, I was told that she was the president of this block and if I want anything done to contact her, because she would fight with me.” And I say, “Well, what are we fighting about?”

Robin Amer: North Lawndale’s block clubs banded together to do things like get a new park, or keep drug dealers off the corner. That day, they would confront a new challenge.

Gladys Woodson: He said, “Did you not know, that it's a dump, an illegal dump, over ‘cross the street?” And I say, “No.” He said, “Come on. Let's walk down there.”

Robin Amer: He walked her to a vacant lot a block from her home.

Robin Amer: So what did you see when you went over there with him?

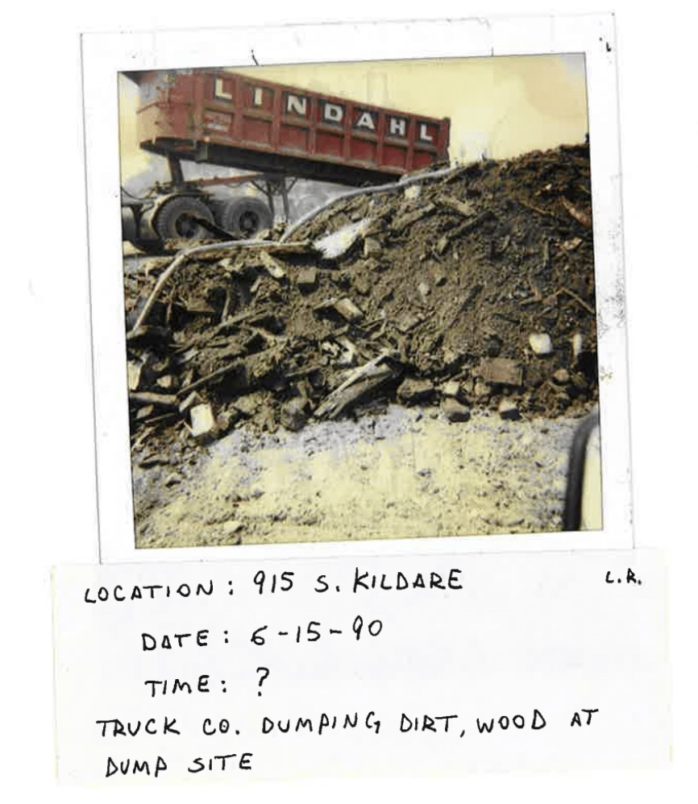

Gladys Woodson: Well first of all I saw a lot of trucks lined up blocking the view. And behind the trucks there was a pile of stuff that was accumulating. And it looked like it was a place that they was going to grind up gravel or something.

Robin Amer: She watched the trucks roll down the street, belching diesel fumes and kicking up dust. And once the trucks made it to the corner, they would turn and head into the vacant lot, park, tip up their cargo and dump it.

Robin Amer: And so when you saw this line of trucks and this pile of rubble, what did you think?

Gladys Woodson: I think, “Oh no, we can’t have this over here. This is bad for health, bad for our children, bad for our houses.” You know, it's just going to take our neighborhood down.

Robin Amer: What Ms. Woodson didn’t know, was that just nine blocks away, there was an even bigger dump.

Back in the spring of 1990, if you’d walked out Ms. Woodson’s front door, past the vacant lot where she saw the dumping, past the train tracks, past convenience stores and gas stations and storefront churches, you’d get to Roosevelt Road and another vacant lot.

This one as big as 13 football fields … half the size of the Pentagon. And this one was across the street from Sumner Elementary School, where Delores Robinson taught eighth-grade math.

Delores Robinson: My classroom became Room 114, right next to the office. It was on ground level. So I would open the windows in the morning. And you can hear and see, I kept hearing these trucks, these dump trucks.

Robin Amer: They were the same trucks Ms. Woodson had seen, and they were dumping here, too.

Delores Robinson: There was bricks and stones and concrete, and, you know, iron, and just all kinds of construction debris.

Robin Amer: The average dump truck can haul up to 24 tons of stuff, and each new truck that came into the lot would add to the pile.

Delores Robinson: It started to grow, and sort of get like a little bump. And then a little hill. But I could see a mountain growing.

Ms. Robinson had been at Sumner Elementary for more than 20 years. She’d arrived in North Lawndale soon after it changed from a white neighborhood to an almost entirely black one. A hundred thousand people lived in North Lawndale then. Factory jobs were abundant, and people walked to work at Zenith and Sunbeam and Sears & Roebuck. Back then, there’d also been an enormous tobacco factory across the street from the school.

Delores Robinson: That building covered blocks. It was a monstrosity of a property.

Robin Amer: But during Ms. Robinson's first decade at Sumner, North Lawndale lost 80 percent of its manufacturing jobs and a third of its residents. Companies either closed up shop or moved out to the suburbs. And along with those departures, attention and resources from the city seem to disappear. In segregated Chicago, North Lawndale felt abandoned by the business community and the city. In 1973, the tobacco company moved to the suburbs, and left its building behind.

Delores Robinson: It was just left there. And within a matter of a few years, it became hollow, you know, the breaking out the windows and taking of fence or iron and scrap. And slowly but surely, it deteriorated to an eyesore. It was just, it was horrible.

Robin Amer: Neighborhood kids called it “Ghost Town.”

Delores Robinson: So, I'm a classroom teacher, and my kids now, I’m predominantly seventh and eighth grade. I said, "Guys, you're not going over—don't go across the street to the..."

"Oh, Miss Robinson, we go through there all the time."

"What?"

"Yeah, we go over there all the time. It's fun going in and out the halls."

I said, "It's dangerous. You can be hurt."

"No, we're cool. We're okay."

Robin Amer: Ms. Robinson once described herself to me as “five feet tall in sandals”—smaller than many of her eighth grade students. But still, she saw herself as their protector.

Delores Robinson: I said, "I'm gonna be looking out this window. I better not see one of you, my students, come out of that building. If I see you going in and out that vacant building, you gonna be in trouble with me." I said, "And it's because I love you, because I care. I don't want you hurt."

Robin Amer: But she later heard a story about someone who did get hurt. Ms. Robinson remembers him as a boy, 12 or 13 years old, who fell three stories from a fire escape.

Delores Robinson: It was one of the ladders that you come down. He was on one of those rot—it had rotten and rusted. It swung, and it broke, and he fell. And he was seriously injured.

Robin Amer: Ms. Robinson thought of him when she looked out her classroom window that spring day and saw the trucks arrive.

She and others had pushed for years to have that factory torn down. And when it finally was in the mid-1980s, it was a victory. A threat to her students, neutralized.

But now a new threat—a new form of blight—was coming to take its place.

Delores Robinson: I started to worry about what is over there? And how is it affecting the environment of these kids over here? I said, "This is so dangerous for our babies."

Robin Amer: How could someone set up an illegal dump across the street from a school and houses and a church?

I want you to picture a dump truck pulling up outside your door, and dropping 24 tons of busted concrete and rusted rebar and bricks and dirt and sand, and then driving away. Then another truck comes, and then another. Imagine this pile growing taller than a child, then taller than you.

What would you do to stop it? Where would you go for help?

Ms. Woodson, the block club president, had lived in a historic greystone since 1970. She’d bought the house after moving to Chicago from her tiny, rural hometown of Vance, Mississippi.

And in some ways, Chicago couldn’t be more different from Vance, which didn’t even have electric lights. But for Ms. Woodson, her block in North Lawndale was also like a small town. She knew all of the neighborhood kids.

Gladys Woodson: I knew they mamas, and they mamas, and we sort of grew up together.

Ms. Woodson and her husband, LC, had raised their kids and grandkids there. And as president of her block, it was on her to protect it.

Gladys Woodson: You just don't let nobody come in and just take away your livelihood.

Robin Amer: So, she and her neighbors started staking out the lot, to see if they could figure out how to stop the dumping. And as they did, they saw that the trucks kept coming by day, and also, in the dead of night.

Gladys Woodson: We have come out here, like, one or two o’clock at night to watch the trucks go in and take down license plates number.

Robin Amer: One and two o’clock in the morning?

Gladys Woodson: Three, four in the morning. And we used to meet them up here because we figured that we can get the license plate number, we can turn them over to the police. So, what we did, we started getting license plate numbers, and what we found, he had one set of plates on the front and a different set of plates on the back.

Robin Amer: It seemed really suspicious. And that was before they saw the man in charge.

Gladys Woodson: Any time you see anybody drive over in a vacant lot in a limo you know it's no good.

Robin Amer: Oh my gosh. What did you think was happening back there, when you saw him drive up in a limo?

Gladys Woodson: I just thought he was a, I don't know, gang banger or something or other. You know, I didn't know what to think.

Robin Amer: The man in the limo was a heavy-set white guy, with a gruff voice and a receding hairline. His name was John Christopher. And he wasn’t just dumping debris in North Lawndale. He was laying bare the city’s ugliest divisions and its starkest divides.

ACT 2

Gladys Woodson: OK. This is a letter that the South West United Block Club Council wrote to a lot of peoples.

Robin Amer: Ms. Woodson and her neighbors didn’t know who John Christopher was yet. But their neighborhood had already been overrun by trucks and debris, and it seemed like the damage could soon be permanent.

So following their stakeout, Ms. Woodson and 20 of her fellow block club presidents crammed into her living room. Anyone who couldn’t fit on the cream-colored sofa spilled into the dining room or sat on the plush carpeted floor.

The presidents of the 1500 Block and the 4300 Block were there—representatives from around the neighborhood. Together, this coalition drafted a letter.

Gladys Woodson: We, the Southwest Lawndale United Block Club Council, are requesting that you intercede for us.

Robin Amer: They sent the letter to the zoning board. And the water department. And to the Department of Streets and Sanitation. They sent the letter to their alderman—which is what we call City Council members in Chicago. They sent it to the mayor and a member of Congress.

Gladys Woodson: We wrote everybody from who's who to who's that!

Robin Amer: And how optimistic were you in those first few weeks and months that you could that you could deal with this problem and make it go away?

Gladys Woodson: Well, I thought once we contact all of these peoples, and they found out what was going on, that somebody would stop it.

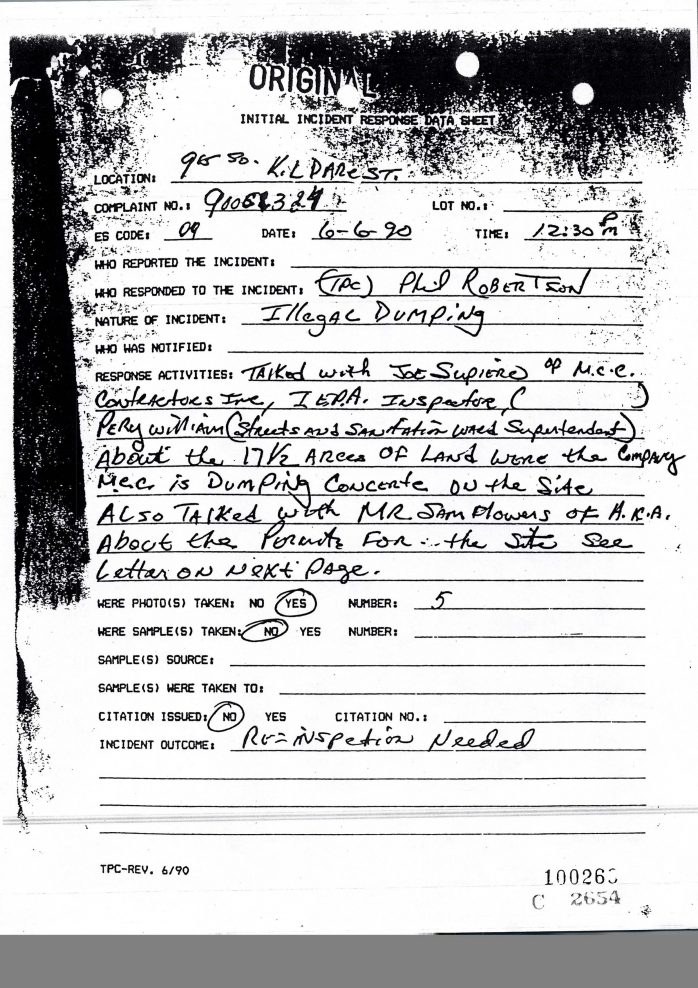

Robin Amer: Ms. Woodson was right, at least at first. In June 1990, about a month after receiving her letters, the city finally sent an inspector to check out the lots.

And when he got there, the inspector saw piles of debris he’d later describe as “taller than you and I”—more than six feet tall already.

So the inspector called his boss and said, “We’ve got a problem.”

Henry Henderson: People who were working as inspectors in the city called me up and said, "We've got this huge amount of material building up in this particular site."

This is the inspector’s boss: a city lawyer named Henry Henderson who specialized in environmental issues.

Henry Henderson: It was a huge mound, and it was across the street from a school. So we got in our cars and went out to visit it. And it was, this is a gigantic, gigantic issue.

Robin Amer: Henry Henderson had learned that John Christopher, the guy Ms. Woodson saw in the limo, was actually running the dumps. So Henderson called Christopher into his office for a meeting.

Robin Amer: Was that the first time that you had met with him?

Henry Henderson: Yes.

Robin Amer: What did he look like? How did he speak? What impression did he leave on you?

Henry Henderson: He's a very, very large person. He had one of these incredibly colorful sweaters on, you know.

Robin Amer: What, like a Bill Cosby dad sweater?

Henry Henderson: Kind of like that, yeah. And I was struck by the fact that it looked like he had his nails done.

Robin Amer: Going into this meeting, Henderson thought he could demand that John Christopher stop, and that he would.

But John Christopher had permits he’d gotten from the city to operate a rock crusher—a giant machine that pulverizes concrete into gravel, which can then be sold back to construction companies to use in their building projects.

Henry Henderson: That was his story about what he was doing. And he was particularly aiming at, "This is construction debris that can be recycled, and I want to crush it, and the material has value. So I'm a recycler and I'm a beautifier." That was his claim as to what his activities were about.

Robin Amer: John Christopher was dumping thousands of tons of construction waste across the street from a school, and people’s homes, and businesses. But the way he put it to Henderson, he was helping North Lawndale.

You’ll hear a lot about John Christopher in this story, but you won’t hear from him, at least not yet. I’ve spent years looking for him, and if he is still alive, he’s likely living under a new name. But I’ll get into that later.

We did talk to someone who did business with John Christopher during this time. This source worked for another local construction company that actually did recycle concrete as part of its business. He didn’t want to be named because he wasn’t authorized to talk to us and he was afraid of losing his job.

He told us that John Christopher owed people money.

And we didn’t hear this from just this guy. Not long after John Christopher started dumping in North Lawndale, another local construction company sued him in county court, alleging he owed them nearly $80,000.

Then, one day, around this same time, our source gets a call from John Christopher, who says, “Meet me in North Lawndale.”

So our source drives to the lot and sees the dump. At first, he’s confused. But then John Christopher explains. This was how he was going to pay the guy’s company back.

See, construction companies usually pay to dump in legal, permitted landfills. John Christopher was offering up his lots in North Lawndale as a cheaper alternative. A legal dump charges, say, $150 a load. John Christopher was asking for as little as $10 a load—a figure he later admitted to in court. He’d allow this guy to dump for cheaper than he would at a real landfill and gradually make up what he owed.

John Christopher pitched it as a win-win. He would repay his debts, and the source’s company would save a bunch of money by dumping on the sites—illegally. And the more all these companies dumped in North Lawndale, the more money John Christopher would make, and the more these construction companies would save.

But this guy wanted nothing to do with John Christopher. When he looked around, he saw piles of stuff everywhere—way more than anyone could reasonably crush. And, there was stuff that couldn’t be crushed—sand, dirt, rebar. Our source told us that guys like John Christopher give rock crushing a bad name.

* * *

As the spring of 1990 turned into summer, despite complaints from neighbors and the letter-writing campaign, and the visits from inspectors, and the meeting with city lawyers, it became clear that John Christopher was not going to stop dumping in North Lawndale.

The noise and the dust had gotten worse. Some of Ms. Woodson’s elderly neighbors relied on oxygen tanks, and the dust was making it harder for them to breathe.

Gladys Woodson: So a group of us, we walked over there to talk to John Christopher. And we asked him, could he stop grinding or whatever he was doing over there?

He told us he could do whatever he pleased. And we told him, “Well, OK, we'll go to court.”

And he said, “If you do go to court, when I leave, I'm gonna leave everything just like it is now.” He was very arrogant.

Robin Amer: When a city gets rebuilt, it puts its new skyscrapers and parks and monuments front and center.

It doesn’t always want you to see how these things got built. Or who got hurt in the process.

Robin Amer: And so you go over, you meet this guy for the first time. You tell him, “Hey, we have breathing problems. We have senior citizens. We've got kids.” And his response is basically—?

Gladys Woodson: “So?” That was his response, “so?”

Robin Amer: OK, so how did you feel after that confrontation?

Gladys Woodson: Let's get him. Let's go to court.

Robin Amer: That’s next time on The City.

CREDITS

Robin Amer: The City is a production of USA TODAY and is distributed in partnership with Wondery.

Our show was reported and produced by Wilson Sayre, and Jenny Casas, and me, Robin Amer.

Our editor is Sam Greenspan. Ben Austen is our story consultant. Original music and mixing is by Hannis Brown.

Additional production by Taylor Maycan, Isobel Cockerell, and Bianca Medious.

Chris Davis is our vice president for investigations. Scott Stein is our vice president of product. Our executive producer is Liz Nelson. The USA TODAY Network’s president and publisher is Maribel Wadsworth.

Special thanks to Misha Euceph and Danielle Svetcov.

Additional support comes from the Fund for Investigative Journalism and the Social Justice News Nexus at Northwestern University.

Archival audio courtesy of WBBM Newsradio 780 and 105 point 9 FM.

If you like this show you may also like WBEZ’s new podcast, On Background, which takes you inside the smoke-filled back rooms of Chicago and Illinois government to better understand the people, places, and forces shaping today’s politics.

I’m Robin Amer. You can find The City on Facebook or Twitter at the city pod, or visit our website, where you can see photos of our characters and an augmented reality version of John Christopher’s dumps. That’s thecitypodcast.com

PEOPLE

PLACES

READ MORE

The document below is the incident report from a city of Chicago inspector from the summer of 1990. This is the first documented inspection of one of the illegal landfills. The city would later find out that these dumps were operated by a man named John Christopher.