S1: Episode 10

The Present, The Future

The uncertain fate of the lots in North Lawndale, and what that says about a city like Chicago.

Episode | Transcript

The Present, The Future

Robin Amer: In North Lawndale today, the 21-acre lot across the street from Sumner Elementary School looks, at first glance, like an open prairie.

In the winter, when the first snow sticks, it looks almost like an untouched nature preserve. In the summer months, tall, dry grass blows across the entire expanse of empty land.

White lace wildflowers dot the landscape, along with plastic wrappers and other household trash. Semi-truck tires and chunks of broken concrete are strewn about like rocky outcroppings. And even with all the plant life, in aerial photos of the lot, you can still see the concrete outlines of factory foundations.

Twenty years have passed since John Christopher’s illegal dumps were finally cleared from this land.

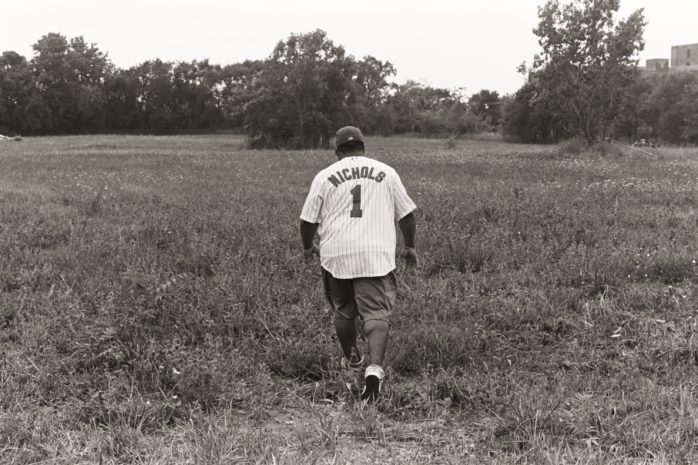

And back then, when the last loads of debris were trucked away, Deyki Nichols was in high school. You’ve heard from him before. He was a student at Sumner Elementary School when the dumps were at their peak. Today, he’s the school’s Dean of Students. He’s been working at Sumner since he graduated from college in 2006.

Our producer, Jenny Casas, met up with Nichols at the elementary school this past summer for a walking tour of the lot.

Jenny Casas: Walking up to the edge of the lot, we can see in the distance a line of trees that cuts across the middle of the land. Deyki and his friends used to call that cluster of trees “the forest,” because of the thick foliage around the elevated train tracks that run through the middle of the lot.

The train viaduct was the dividing line between what they called “the hills,” the piles of debris closest to the school, and what they called “the mountains,” the piles that reached up to six stories tall on the other side of the viaduct.

You could see the trees even when the hills and mountains were here. But they especially stand out now, against the emptiness of the lot.

There’s no fence around the lot—anyone can walk right into it. As we were about to take our first step in, Nichols turned back to grab something from his car.

Deyki Nichols: Get my bat out my trunk.

Jenny Casas: A baseball bat, “just in case.” He tells me there are coyotes hiding out in the lot.

Deyki Nichols: It used the shock me to see—we got uh, two students that's always late, and he walks through here. I told him, I’m like, “Man, there’s coyotes over there. You better from stay from over there.”

Jenny Casas: I couldn’t tell whether he was joking. Or, if was the modern-day version of the scare tactic he heard as a kid to keep him out of the lot—this time with coyotes instead of an evil rabbit.

Deyki Nichols: Oh, I ain't been over here forever. Yeah, I haven’t been 20, 26 years. You want to go through there?

Jenny Casas: Yeah?

Deyki Nichols: Yeah? All right, come on, let's go.

Deyki Nichols: You got make your own trail. Used to be a trail, though.

Jenny Casas: From you walking through here?

Deyki Nichols: From us walking through here, yeah. Oh, you get me, uh, wowee. We're in the middle of the forest. Uh, bunch of grass, a bunch of trees. And um, oh, a lot of memories.

Jenny Casas: We scrambled up to the top of the viaduct and walked along the train tracks. He tells me about how he and his friends built a secret clubhouse with discarded cardboard signs. About how they rode the slow-moving trains. About a friend who jumped off at the wrong time and caught his leg on a train switch.

We have a bird’s eye view of the street from up here—of all the houses and storefronts, a gas station and the remaining factory buildings. We can see the skyscrapers of downtown in the distance. We pause to look at the part of the lot on the other side of the train tracks—a vast tract of land you couldn’t see from up here in the mid-’90s, because of the wall of construction debris blocking the view.

Robin Amer: After the dumps were cleaned up, this empty lot presented an opportunity.

The lot is a straight shot six miles west from downtown, with easy access to public transit and the Eisenhower Expressway.

Especially after the embarrassment of Operation Silver Shovel, this newly available land offered a chance for Chicago’s so-called renaissance to touch down in North Lawndale—not to offload unwanted trash, but to build something new.

The lot was like a blank canvas. It could remain empty, or, with the right kind of project, it could bring jobs and money back into the neighborhood.

But 20 years later, the lot is still empty. And that emptiness represents a different kind of blight. Not the overwhelming presence of the Mountain, but abandonment.

The Mountain might be gone, but it turns out that it’s far easier to dismantle a six-story dump than to fix the system that created it.

I’m Robin Amer, and from USA TODAY, this is The City.

ACT 1

Robin Amer: As the 1990s turned into the early 2000s, Chicago’s so-called renaissance crept westward from downtown, bringing new development a little closer to West Side neighborhoods like North Lawndale.

Old West Loop factory buildings were converted into condos. The old stadium nicknamed “the Madhouse on Madison” was torn down and replaced by the United Center, a hulking arena home to the Bulls and Blackhawks. West Side elevated train lines were given a facelift.

And in 1999, the city came forward with a plan to redevelop the lot where John Christopher's dumps once stood—a plan to fold North Lawndale into the westward march of development.

Jenny’s going to take it from here.

Jenny Casas: Almost as soon as the lot was cleared, then-Mayor Richard M. Daley made a public commitment to build on the lot. The day before he announced his 1999 bid for re-election, he stood outside Sumner Elementary School to announce his support for a major development on the empty land across the street from the school.

The project Mayor Daley was there to announce was an entertainment studio—a $150 million entertainment studio. A place with indoor sets to film TV shows and movies. The proposal included six sound stages, a 30,000 square-foot production studio, and state of the art digital and satellite technology.

The head of the production company grew up on Chicago’s West Side. He said he wanted to use the studio to launch a new TV network that would make shows for and about black families. He believed the studio would employ more than 700 people, many of them from the West Side.

This was a major investment from private industry that North Lawndale hadn’t seen since companies like Sears & Roebuck, Zenith, and Western Electric had factories in the neighborhood.

The city threw its weight behind the project—in cash. Mayor Daley pledged $25 million in city funds to help make it a reality.

The city also used eminent domain to seize several properties on the lot. Residents that lived in those buildings were paid to leave, so the city could clear the land of all existing structures. Everything would be leveled a year later.

Think about the possible impact of a development like this: in addition to jobs, it could raise property values, draw in new residents, and spark additional investment.

It was also novel. Neighborhood residents were excited about the proposal. Michael Scott Jr. grew up in North Lawndale. He was in his early 20s and away at college when he first heard about the movie studio.

Michael Scott Jr.: My thought was, man, this is going to be really cool. Maybe I should change my major and go into film and broadcasting, because I can come home and have something in my community in which I can be employed and possibly make a lot of money.

Jenny Casas: Despite the excitement in the neighborhood and backing from the city, the project had trouble getting off the ground. Financial problems caused years of delays.

Even Mayor Daley eventually backtracked. He told the Chicago Tribune in 2002 that there was no guarantee the studio would ever be built.

Over the next few years, news articles would declare the project “back on again with a vengeance.” But then the scale of the project was reduced to a third of the original plan.

Other critical funding fell through, and the movie studio never broke ground.

Because the movie studio failed the land was still available for something else—something even more dramatic and high-profile.

Steve Inskeep: Now let's talk for a moment about presidential legacies. There are 13 presidential libraries run by the National Archives. When President Obama leaves office, the construction of the 14th will begin. A nonprofit foundation created to build the Obama Presidential Library is considering proposals from several contenders to host the library…

Jenny Casas: One of those contenders? The Silver Shovel lot. Yes, the land John Christopher dumped on was now in the running to be the new home of the Obama Presidential Library.

Organizers from North Lawndale teamed up with officials from the University of Illinois-Chicago, or UIC. Together, they laid out a pitch that would transform the lot into an ultramodern campus with futuristic buildings and manicured landscaping. It looked like it could have been the headquarters of a tech company in Silicon Valley.

The UIC plan also included an elevated greenway, like New York’s Highline. And it planned for a new bus route that would have connected North Lawndale to the university campus.

Obama’s former chief of staff and Mayor Daley’s successor, Rahm Emanuel, committed to donating the vacant land to the Obama Foundation. Emanuel also pledged to re-open a station along one of the city’s public train lines to better connect the library to other parts of the city.

This plan would have brought development to North Lawndale—and connected it to the city’s renaissance.

In September 2014, North Lawndale was announced as a finalist. Alongside it were sites in: Hawaii, where the president was born; New York, where the president went to college; and the South Side of Chicago, where the president got his start in politics.

UIC made a promotional video in support of the North Lawndale site. The video was shot at Sumner Elementary School and highlighted the people that would be across the street every day—the students. The video was called, “Obama Library, signed, sealed, delivered,” appealing directly to President Obama. It was named after the Stevie Wonder song the president had used on the campaign trail.

In the video, students from Sumner are gathered in the auditorium. Two boys in matching ties get up on stage to address a crowd of their peers. All the students are wearing white t-shirts with red lettering across the chest that reads: “Barack Obama Presidential Library...UIC...North Lawndale...A Shared Destiny of Transformation.”

Sumner student: Most of the time, the West Side gets overlooked and misses out on many opportunities, including educational ones. We would like to see the presidential library in the field across from our school, where we see trash every day. This would bring hope for a better community and uplift the next generation. In closing, we beseech you to consider the North Lawndale area in placement for the Barack Obama Presidential Library. Thank you for your consideration. [Applause]

Jenny Casas: Deyki Nichols, who was by then Sumner’s Dean of Students, was in the auditorium when the video was filmed. He wanted the changes the Obama Library could bring.

Deyki Nichols: We was fighting for it. We was fighting for it. I mean, because we knew them bringing that library here, everything, you know, the hanging out at the liquor stores, the abandoned buildings, all that got to get fixed. They can't hide that, because we got—it's gonna be world-renowned. With tourists and people from all over the world is coming now, and they coming to the West Side, so we're not gonna have an eyesore.

Jenny Casas: The Obamas did choose a site in Chicago—just not in North Lawndale.

Melba Lara: There are reports that Chicago’s Jackson Park has been chosen as the site for President Barack Obama’s Presidential Library...

Jenny Casas: Instead of North Lawndale, the Obamas chose Jackson Park, on the city’s South Side. This public park is right by the University of Chicago and the city’s greatest natural feature: Lake Michigan.

There’s a long history to the tensions between Chicago’s South and West Sides that has everything to do with power and privilege. Parts of the South Side have long been home to the city’s black elite. And it’s worth noting that the Obamas are Southsiders. Michelle Obama was born and raised on the South Side. The couple raised their children there and the president taught law at the University of Chicago.

Given all that, most North Lawndale residents we heard from weren’t surprised that the Obamas chose the South Side over the West Side. But they were still disappointed—Obama won the presidency with declarations of hope and change.

Deyki Nichols: If he was, uh, big on change, what more, what more area need change than this part of Chicago? The West Side.

Robin Amer: During the 1996 cleanup, Mayor Daley had stood on the lot and proclaimed, “We will work tirelessly until the site … can be an asset to the North Lawndale community instead of a liability.”

And if the site of John Christopher’s illegal dump had been transformed into a landmark devoted to the nation’s first black president, it would have meant that the promises made to the neighborhood in the wake of Silver Shovel weren’t empty after all.

But even after this plan fell through, a third plan emerged. It wasn’t as flashy as a movie studio or a presidential library, but it offered the potential for another kind of change.

That’s after the break.

ACT 2

Robin Amer: Over the past 20 years, with all the back and forth on potential development plans, some North Lawndale residents have become skeptical that a major development will ever come to the land where the Mountain once stood.

But they have always seen the lot’s potential to address the neighborhood’s needs.

Jenny Casas: What do you want on the lot? If you could snap your fingers and have something there?

Rita Ashford: I'd like for school to go there.

Sherina Ashford: Stores or something, that maybe we don't have to go so far to the stores.

Johnnie Baker: Being a senior, I'd like to see maybe senior housing there.

Margaret Milam: I would like to see something that will, is going to employ people.

Gladys Woodson: I would like a supermarket over here. You know, so you won't have to go out of the neighborhood in order to purchase food.

Debra Wardlow: Low-income houses for people that can't afford the high rent that's in Chicago.

Michelle Ashford: A community center—something to build our children up. I mean, anything instead of keep looking at all these lots.

Robin Amer: But for all the attributes that make this lot a prime piece of real estate, there are also some very real practical hurdles to redeveloping that land.

We started looking into those hurdles after we heard about the space suits.

We heard about them from Gladys Woodson, the block club president who spent so many years fighting John Christopher.

When she moved to North Lawndale from her hometown of Vance, Mississippi, 43 years ago, she was considered the baby of the block. Now, she’s become the neighborhood matriarch and she still runs what’s left of her block club.

The first time I went to the site with Ms. Woodson, she told me something that would echo through the conversations I’d later have with other North Lawndale residents.

Gladys Woodson: And a lot of that stuff they dumped was hazardous, and you ask me, how do I know it was hazardous? Because when the people come to remove it, they was wearing masks and space suits.

Robin Amer: When she says space suits, she’s talking about hazmat suits. Or at least the white suits and helmets EPA officials wore when they came to inspect the lot after Silver Shovel broke

Gladys Woodson: So that tells me, when I walked over there, I shouldn't have been over there.

Robin Amer: And ever since the cleanup, a question has lingered for Ms. Woodson and others: How contaminated are these lots today? The city has never told them.

The answer to this question is important, not just for their peace of mind, but because the answer has implications for what can be built on the lot today.

Soil samples from the lot show low levels of heavy metals in the dirt—metals like lead, arsenic and mercury. Those contaminants were likely there long before John Christopher turned the site into an illegal construction debris dump. They likely come from the factories that used to be on the lot, including a tobacco factory, a rubber factory and a door hinge factory.

So the site is contaminated but it’s not a superfund site—land that poses a serious danger to the general public.

These lots are called brownfields. The contamination levels here are on par with thousands of other empty, post-industrial lots around the city, most of which are also in majority black and brown neighborhoods.

But if a developer wants to build anything on a brownfield, they often have jump through hoops to meet safety standards that would be easier to achieve on a pristine piece of land.

There are many options for making a brownfield safe. The more expensive route involves digging down several feet, hauling out the contaminated soil and hauling in tons of clean soil as a replacement. But the larger lot in North Lawndale is 21 acres, and remediating a parcel that big gets very expensive very fast.

One cheaper option is to cap the land with something like concrete, to create a barrier between the contaminated soil and the people around it. That was the plan proposed for the movie studio.

So, there are additional hurdles to developing a brownfield site … hurdles that have come into play in the most recent attempts to redevelop this land.

Jenny is going to pick it back up from here.

Jenny Casas: Michael Scott Jr. never did change his major and go into the movie business. Instead, he went into politics. He’s the current alderman of the 24th Ward. He won the seat once held by Bill Henry—the former alderman who was in office when John Christopher started dumping in the ward.

Alderman Scott was elected a month before North Lawndale lost the bid for the presidential library. And once in office, he was in a position to actually make decisions about development on the land.

Michael Scott Jr.: And I went to the Department of Planning and I said, “Hey, we're not going to have any Obama Presidential Library. I really would love to figure out how to develop this land.”

Jenny Casas: Alderman Scott had wanted something that would rival the Obama Presidential Library—a basketball hall of fame or a similar destination site that could draw large crowds into North Lawndale.

That is until he met with representatives from Clarius Partners—a development group that was interested in building something very different on the land.

Michael Scott Jr.: So we're heading west on Roosevelt from my office, which is on the 4200 Block of Roosevelt. Headed down to the large parcel of land that used to be the Silver Shovel site.

Jenny Casas: This past summer, the alderman and I walked over to the lot where Clarius Partners hopes to build.

The plan includes several-hundred-thousand square feet of light industrial space—big warehouses for what are called “last-mile logistics.” That’s basically a building that can store a product after its been made and before it’s been delivered to consumers. They also want to build retail along Roosevelt Road.

Alderman Scott is a natural politician—a skill he probably learned from a lifetime surrounded by politicians. His father was the president of the Chicago Board of Education and an ally of Mayor Daley. As such, Alderman Scott is good at selling his vision for what the lot might look like if it were developed today.

Michael Scott Jr.: Where we stand now, I see a grocery store. I don't know if that, if my vision is gonna come to fruition, but I see a nice grocery store, very clean. And then, right in the middle, in between both of them—

Jenny Casas: Where those tires are?

Michael Scott Jr.: No, a little bit further, a little bit further than the tires. I see maybe six or seven businesses. So I see all that. I don't know if you see it, but I see it. It's right there. And then back here all industrial, nice landscaping—a far cry from what it is currently.

Jenny Casas: A few months ago, I found some old pictures from a school carnival held at Sumner Elementary School in 1995. You can see John Christopher’s dumps in the background. When the photo was taken, Silver Shovel hadn’t made the news yet. The youngest kids in the photos wouldn’t have known North Lawndale without the Mountain.

I mentioned the photo to Alderman Scott while we were out there because I wanted to know whether he was worried about the impact on students. If the picture were taken today, would there be a line of delivery trucks instead of the piles of debris?

Jenny Casas: [Sigh] Are you worried at all about—

Michael Scott Jr.: Traffic?

Jenny Casas: Traffic and trucks and the kids and—

Michael Scott Jr.: Nope, nope, nope, nope. So there's already been a traffic study done by Clarius. We will try to exit—have everything exit and enter on the main thoroughfare which is Kostner. Kostner, you can get on the expressway on 290…

Jenny Casas: The Clarius Partners proposal is considered “light industry,” but industry all the same. A far cry from a presidential library or a studio where blockbuster films are shot, but definitely in line with the industrial legacy of the lot.

Remember, from the 1960s to the early 2000s, North Lawndale had lost tens of thousands of manufacturing jobs. And Alderman Scott wasn’t enthusiastic about the development with Clarius Partners until he realized that a project like this one could bring back some of those jobs.

Michael Scott Jr.: When they first pitched it to me, I was like, bleh, no. I don't want that. I don't see this for my community. And in my mind, I was set on a destination. But as I did more research, and I did more research on industrial complexes in the city of Chicago, and how many jobs they bring to a community, and to a community that needs jobs and needs it desperately, I thought to myself, “This can be something that is more transformative than an Obama Presidential Library.”

Jenny Casas: Kevin Matzke, the managing principal and founder of Clarius Partners, says the company was drawn to the site by many of the things that had drawn others there—everyone from John Christopher to President Obama.

Kevin Matzke: Twenty acres of available land close into the city of Chicago, and that in its own right is a pretty rare commodity. That's the initial attraction to us—that it was a sizable, scalable-type land site, vacant, uh, easy for trucks, employees in cars, to get on and off the expressway, get in and out of the city of Chicago.

Jenny Casas: Matzke hopes that the project, if it’s built, might become an anchor for more development—the inverse of the what we saw with the illegal dumps, where waste just attracted more waste.

Kevin Matzke: Our hope is that by investing, we can improve property values. That we can add to employment. All these benefits. We happen to think that our project is net-net a huge win, a huge benefit.

Jenny Casas: A good portion of the people we talked to hadn’t heard about the proposal. For those who had, opinions are mixed.

On the one hand, they see its potential to create jobs, revitalize other businesses, raise property values and draw in more residents.

Others are wary of the downsides that could come from this or any other big development—higher rents or property taxes that could make it hard for long-term residents to stay. Or the diesel truck traffic that would likely come from having new industrial space there.

But reality has yet to catch up with Alderman Scott’s vision. Once again, money is the sticking point.

The Clarius Partners project has been in the works for three years, since 2015. The city owns the land, and has agreed to reduce the cost from $2.5 million to around $1 million.

But complying with brownfield remediation standards is expected to cost an additional $5 million dollars. That additional cost has left this deal in a financial stalemate—it’s not dead, but it’s not racing forward either.

Still, Alderman Scott says he wants to see something built there.

Michael Scott Jr.: If you give up, then you definitely won't get anything. And so, my thought process is, I'm not going anywhere. I've been here for 40 years. I'm not leaving anytime soon. And as long as I'm here, I'm going to throw stuff to the wall and see if it sticks.

Robin Amer: That’s after the break.

ACT 3

Robin Amer: Across the street from where the dumps once stood is one of the biggest churches in North Lawndale. United Baptist is a modern-looking brick building with a peaked roof and bright stained-glass windows. It stands apart from the other buildings on Roosevelt Road.

If you enter the church through the parking lot, take a right, and go down a switchback of stairs, you’ll find yourself in the church basement.

It’s a big room with linoleum floors and a few dozen circular tables dressed in yellow and white plastic tablecloths. On a Thursday this past March, about 75 people were seated facing the front of the room, where Alderman Scott stood behind a lectern.

Michael Scott Jr.: Good evening. In the interest of time, although we're missing a few guests, we're going to get started. I'd like to welcome all of you to the 24th Ward community meeting...

Robin Amer: These monthly meetings are often held in this basement. There’s usually a panel of speakers—elected officials, police officers, community organizers. And Alderman Scott is the emcee, adding his own commentary in between.

At this meeting, he brought up a complaint he frequently hears from the neighborhood.

Michael Scott Jr.: So, I get a lot of calls almost every day from residents in our neighborhood saying, "Hey, is the city going to get out and clean our block?" We have to be mindful that in North Lawndale, there are over 3,000 vacant lots.

Robin Amer: It’s hard to get a precise tally on the exact number of vacant lots in North Lawndale. But Alderman Scott cites anywhere between 2,500 and 3,000 abandoned lots spread across North Lawndale’s three square miles. Given the magnitude of the problem, he encourages the people at the meeting not to wait for the city, but to take action themselves.

Michael Scott Jr.: Just pick up the front of your house. If you pick up the front of your house and maybe grab something to the right or the left of you, our community will look a lot better than it does now.

Robin Amer: At another one of these monthly meetings, residents echo the concerns about garbage and vacant lots—one man has even made cleaning up the neighborhood his personal mission.

Sel Dunlap: Good evening. My name is Sel Dunlap. I have a campaign called a “war on filth and fear.” Living in a dirty, filthy community is a trauma. It's a trauma. To the point that if you live in it long enough, it can take up residency in you. To the point you don't have the self-respect you should have. Our children walk by garbage going to school. We step up in our churches. Stepping over garbage and trash. That's where I have defined my and our devil. Thank you. [Applause]

Robin Amer: Vacant lots can be an opportunity, or they can be a blight. But the sheer number of empty lots in North Lawndale illustrates the magnitude of the challenge of redevelopment here. The 21-acre Silver Shovel site is not alone.

Let’s go back to Jenny.

Jenny Casas: I want to be clear, it’s not that there hasn’t been any development in North Lawndale. Development has come west from the Loop to the eastern edge of North Lawndale—the edge closest to downtown.

Over the past ten years or so, a community health center has been built, a Lagunitas Brewery, a different production studio and a big charter school.

But there’s a widespread feeling among residents we spoke to on the west side of North Lawndale that the brewery or the health center are not developments for them. That the lot where the Mountain once stood will never be developed. At least, not as long as they are still living in the neighborhood.

A lot of people we spoke with shared this belief, but Rita Ashford was the most direct about it.

Rita Ashford: They not going to invest anything here. People, if you have something, you hold on to it. Because they want this land to develop it for people in the suburbs. So white people can move back here, because it's easily accessible to the Loop.

Jenny Casas: Ms. Ashford and others feel like the city will ignore problems in the neighborhood until the mostly black residents eventually all move out, leaving it open for a community that looks nothing like Ms. Ashford’s.

Rita Ashford: That is exactly what they're doing. They figure, well, they letting it go. It's bad people moving away, people moving away.

Jenny Casas: North Lawndale has suffered a dramatic population loss in the past 50 years. At its peak in 1960, the neighborhood was home to almost 125,000 people. More than 70 percent of those residents have since left. Including Ms. Ashford—though not by choice. She moved to the suburbs to help raise her grandchildren. But she's still deeply invested in North Lawndale. She still has family and friends there, and she can imagine a future in which she moves back.

Be that as it may, she is part of a larger exodus that has seen 250,000 black Chicagoans leave the city since the year 2000.

Since the economy has recovered post-Recession, you can find construction cranes all over the Loop and in well-off neighborhoods like Lincoln Park and Bucktown.

There’s a frustration among residents that comes from knowing other parts of the city are being built up while North Lawndale has continued to lose basic city support and services.

Rita Ashford: They’re just letting it deteriorate. Show me that you still have some interest in our community and not still, because I consider it a dying community.

Jenny Casas: To Ms. Ashford, the lack of development at the lot and all the other vacant lots are further evidence of the city's broader neglect of her neighborhood. A neglect she believes is firmly rooted in the same structural racism that allowed her neighborhood to become the dumping ground for the rest of the city.

She sees evidence of this everywhere, not just in the vacant lots.

Take, for example, the field house where we did our interview. It’s in a small public park a few blocks south of the big vacant lot. Ms. Ashford and her daughter Michelle say it looks like nothing has been planted there for years.

Rita Ashford: When I look at the front of this park, it looks so bad. During the time, we uh, we fought for this park. We used to be on the advisory council. It's no excuse for the front of that park to look like it is. It looks horrible.

Jenny Casas: The neglect the Ashfords see starts small—with the neglect of this public park.

From there the neglect gets bigger. The park isn’t being used as much these days because it doesn’t always feel safe.

Rita Ashford: We couldn't have stuff in the park. They shoot up the park. How many times we done sit and call the police about them gang fighting in this park?

Michelle Ashford: It will take them 10 to 15 minutes to get down here when you got a 9-1-1 call. Shooting, somebody shot. Somebody stabbed. These are priority calls.

Jenny Casas: Adequate policing is obviously something the city is supposed to provide to every community. But the Ashfords say they don’t see it in North Lawndale.

And when the police do come, Ms. Ashford says they don’t treat North Lawndale residents with respect. She has a troubling example on hand.

Rita Ashford: I remember when uh, what's that kid got killed right here? Chicken. They called him Chicken. He got shot and killed right here at the park, outside the gate. When the police came, and they roped it off, and I want to tell you how, when they put him in that body bag, how they bumped his head all against the end of the paddy wagon. It was so—it's just a sense of disrespect.

Jenny Casas: For Ms. Ashford, all of these things—the unkempt park, the shootings, the absence of the police, the disregard for black bodies— they’re all root causes of the emptiness in the neighborhood: the vacant lots, the population loss, the lack of development. It also signals to her a deeper-rooted, intentional neglect.

Rita Ashford: You know, and the most important thing is, it's the racism. That's our main problem right here.

Jenny Casas: To her, it’s all proof that the city will only find time for North Lawndale if there’s scandal—another Silver Shovel. Or, of course, if residents just cleared out.

* * *

Robin Amer: When I first heard about the six-story Mountain of debris in the middle of a residential neighborhood, I was seized with a question: How could this happen? It was a question I kept asking again and again.

The answers—the overlapping layers of corruption and apathy, the failures of individuals and institutions, the deep-seated legacies of segregation and racism—made clear that while the Mountain was extraordinary, the forces that put it there are as commonplace as they are insidious.

Ultimately, it’s not just about the Mountain, or about the vacant lot left behind after the cleanup. It’s not even about what happens when a community is deemed the appropriate place for a city’s waste.

It’s about the way a city like Chicago treats a neighborhood like North Lawndale. It’s about what happens when a city sees a whole neighborhood is seen as disposable—as unworthy of urgent action in the face of a worsening crisis.

The Mountain was a tragedy, but it was also a symptom of a deep and frightening indifference to communities like North Lawndale.

Whether it’s North Lawndale on the West Side or Altgeld Gardens on the South Side or Northwood Manor in Houston, cities have the power to make some neighborhoods wither and others thrive.

If a city will allow a six-story mountain to exist across the street from homes and a church and an elementary school for nearly a decade, what else will it allow?

CREDITS

Stay tuned at the end of the credits for sneak peek of Season 2 of The City.

The City is a production of USA TODAY and is distributed in partnership with Wondery.

You can subscribe to the show on Apple Podcasts or wherever you’re listening right now. If you like the show, please rate and review us, and be sure to tell your friends about us.

Our show this week was reported and produced by Wilson Sayre, Jenny Casas, Sam Greenspan me, Robin Amer.

This episode was edited by Matt Doig with additional editing from Amy Pyle.

Ben Austen is our story consultant. Original music and mixing is by Hannis Brown. Legal review by Tom Curley.

Additional production by Taylor Maycan, Fil Corbitt, Isobel Cockerell and Bianca Medious.

Our executive producer is Liz Nelson.

Chris Davis is our VP for investigations. Scott Stein is our VP of product. The USA TODAY Network’s president and publisher is Maribel Wadsworth.

Thank you to our sponsors for supporting the show. And special thanks this week to GEI Consultants, Misha Euceph and Danielle Svetcov.

Archival audio courtesy of WBEZ, NPR and the University of Illinois-Chicago.

Additional support comes from the Fund for Investigative Journalism and the Social Justice News Nexus at Northwestern University.

I’m Robin Amer. You can find us on Facebook and Twitter @thecitypod. Or visit our website, where you can see photos of the lot today.

Our live event in Chicago December 5th is sold out, but if you missed out on tickets, we're going to have a live stream of the event. For more information, go to our website.

That's thecitypodcast.com

SEASON 2 SNEAK-PEEK

Next season on The City: We head west—to Reno.

This scrappy city known for gambling and quick divorces has spent decades trying to prove it’s more than just a second-rate Las Vegas. Now some of Reno’s most powerful boosters are fighting to reinvent the city as an offshoot of Silicon Valley.

They’ve taken aim at a potent symbol of the image they’re trying to put to rest: strip clubs.

Ground zero in this battle is an aging but lucrative strip club that sits on the edge of some of Reno’s most valuable land.

The city wants to kick the club out. But the strip club is fighting back.

Mark Thierman: They wanted to see what war is, we’ll show em what war is.

The City, Season 2: Reno. Coming in 2019.

PEOPLE

PLACES

(Photo: W.D. Floyd)

WATCH

This video, created by the University of Illinois-Chicago, captured the excitement many felt that the Obama Presidential Library could have been built in North Lawndale. This rally took place at Sumner Elementary School, which sits across the street from the lot where John Christopher’s illegal dump once stood six stories tall. This now-vacant land was one of four sites that were chosen as finalists for the museum. The Obamas eventually picked a location on Chicago’s South Side.